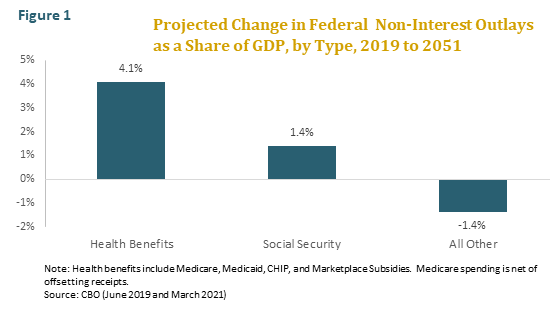

Anyone familiar with the federal budget outlook knows that, along with interest on the national debt, the growing cost of health benefit programs is the main driver of long-term budget deficits. According to the CBO, the cost of Medicare, Medicaid, and the other major federal health benefit programs will increase by 4.1 percent of GDP between 2019 and 2051, while the cost of Social Security will increase by 1.4 percent of GDP and all other spending, except for interest on the national debt, will actually decline as a share of GDP.[1] (See figure 1.)

Sooner or later, policymakers will have no choice but to confront the long-term deficit challenge, which means that they will have no choice but to confront the challenge of rising health benefit spending. With surging inflation compelling the Federal Reserve Bank to increase interest rates, and hence federal borrowing costs, that day may come sooner rather than later. Now may therefore be a good time to correct some of the wishful thinking and mistaken assumptions that have undermined past efforts to control the cost of federal health benefits.

In this issue brief, we focus on three myths about health-care reform. The first is that spending can be painlessly controlled simply by eliminating waste and improving the efficiency of the health-care system. The second, closely related myth, is that the experience of other developed countries with national health systems proves that it is possible for the United States to achieve better health outcomes at lower cost without imposing any sacrifice on beneficiaries. The third is that efficient and fair federal cost control is not feasible unless we first enact comprehensive national health-care reform.

Each of these myths has its roots in a valid observation. The U.S. health-care system is indeed filled with waste and inefficiency. Other developed countries with national health systems do spend much less than we do, yet perform better on many measures of health. And comprehensive national health-care reform might well make federal cost control easier. The conclusions drawn from these observations, however, are deeply flawed. The truth is that controlling costs will require real trade-offs, that countries with national health systems spend less because they set limits, and that federal cost control need not await national cost control. Indeed it must not, since the deficit-financed growth in health benefit spending threatens the nation’s future.

What’s Driving the Projections

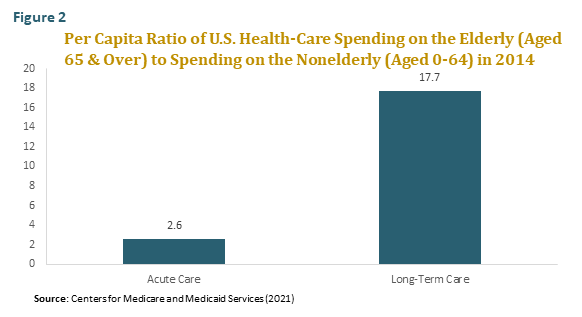

Before directly engaging the myths, it will be helpful to take a quick look at what’s driving the projections of rising federal health benefit spending. There are two forces, the first of which is the aging of the population. As countries move through the “epidemiological transition,” chronic diseases replace infectious diseases as the primary cause of morbidity and mortality. Since the elderly are much more likely to suffer from chronic diseases than the nonelderly, health-care consumption rises steeply with age. Per capita, the elderly consume nearly three times as much in acute-care services as the nonelderly and nearly twenty times as much in long-term care services. (See figure 2.) The elderly, moreover are the fastest growing segment of the population, the older the elderly are the more health care they consume, and the oldest elderly age groups are the fastest growing of all.

According to the CBO, nearly one-third of the projected growth in Medicare and Medicaid spending as a share of GDP between 2019 and 2051 is attributable to the aging of the population, including both the increase in the number of elderly beneficiaries and the rising average age of those beneficiaries. This means that nearly one-third of the projected growth is needed simply to keep delivering the same level of care to each beneficiary, at each age, as we do today. For Medicare alone, the share of projected spending growth attributable to population aging is even larger.

Some experts hope that ongoing improvements in the health of the elderly will lead to large reductions in health-care consumption at older ages, offsetting the projected impact of population aging on health-care expenditures. But as we explained in a previous issue in this series (“Are Health Spans Rising along with Life Spans?,” Fall 2020), this hope is likely to be disappointed. While it is true that rates of elderly disability, as measured by limitations on activities of daily living such as bathing or dressing, have fallen substantially in the United States over the past few decades, the share of the elderly with expensive chronic conditions, from diabetes to hypertension and heart disease, has been flat or rising. Moreover, the obesity epidemic, along with other destructive lifestyle choices, is putting a growing share of the midlife population at risk of premature morbidity, disability, and death. If the health of midlife adults continues to deteriorate, the downward trend in elderly disability rates could stall or even reverse as younger cohorts begin to cross the threshold of old age.

The rest of the increase in Medicare and Medicaid spending as a share of GDP is attributable to growth in real per capita age-adjusted health-care spending—or more precisely, to the projected growth in that spending in excess of the projected growth in real per capita GDP. Unlike the demographically driven component of spending growth, this so-called excess cost growth represents an increase in the relative prices and volume of services delivered to each beneficiary, and so could potentially be reduced without making beneficiaries appreciably worse off than they are today. Reducing it, however, will be far from painless. One reason is that the CBO projections already assume that excess cost growth will be relatively low in the future compared with its long-term historical average.[1] This suggests that we may need serious ongoing cost control simply to keep federal health benefit spending from exceeding the official projections. The other reason, as we will see, is that it is not waste, or at least not primarily waste, that is causing real age-adjusted per capita health-care spending to rise over time.

The Waste and Inefficiency Myth

To be clear, there is no question that there is a vast amount of waste and inefficiency in the U.S. health-care system, which is afflicted by perverse cost-plus incentives and widespread misallocation of resources. Thanks to pathbreaking research by scholars associated with the Dartmouth Health Atlas Project, we know that the per capita consumption of health care shows a wide variation both between and within regions that is uncorrelated with any measurable health need or outcome. If all providers followed the practice patterns of the most efficient providers, this research concludes that health-care spending could be reduced substantially—perhaps by as much as 30 percent. [2]

We should be careful, however, not to exaggerate how easy this savings will be to achieve. The problem is that pure waste is more difficult to identify in practice than in theory. Demonstrating statistically that certain higher-cost tests and treatments are ineffective on a population-wide basis does not mean that they are ineffective in every individual case. There will always be some patients for whom the higher-cost option will produce a better outcome. In fact, the only way one can know with certainty whether a particular medical procedure will be ineffective in a particular case is to perform the procedure and observe the outcome. And indeed, much of the supposedly wasteful spending identified by health policy researchers reflects precisely this sort of post-hoc analysis. It is often said, for example, that it is wasteful to spend so much on patients in their last six months of life. But of course there is no way of knowing what the last six months are until the patients have died. In short, while enforcing systematic adherence to best practice guidelines could eliminate much ineffective spending, it would also eliminate some beneficial spending, which is another way of saying that it would entail cost-benefit trade-offs, some of which will surely involve questions of life and death.

Even if we could painlessly eliminate all of the waste in the health-care system, moreover, it would constitute a one-time savings that does little to alter the long-term growth in health-care spending. The demographic drivers would of course remain. So would the fundamental drivers of excess cost growth. These include the ongoing advances in medical testing, screening, diagnostics, pharmaceuticals, and surgery that are pushing up the cost of the research, technology, and skilled labor underlying every medical visit. They also include the steady rise in the standard of “health” that Americans expect their doctors and hospitals to deliver, which now encompasses everything from good looks and good sex to a better mood and a better golf swing.

Good health, after all, is not a fixed goal. It is a subjective standard that rises over time as societies become more affluent, less tolerant of bad health or risk, and more secular—that is, more apt to see happiness in the here and now as life’s ultimate goal. As growing public expectations about health interact with medical advances, it is transforming the practice of medicine. While once it meant an occasional visit to the doctor or hospital, it is fast becoming a lifelong process of diagnostics and fine-tuning in which any extra dollar spent is likely to confer some perceived benefit. While most health economists would agree that the benefits of the rising health-spending tide may not always justify the extra cost, few believe that most of it is waste in the sense that it confers no benefits at all.

All of this serves to make a fairly simple point: Restraining the future growth of federal health benefit spending is certain to be difficult and painful. Out of fiscal necessity, federal beneficiaries and their providers in years to come will have to lose some of their accustomed freedom to choose the type, variety, quantity, and institutional setting of the reimbursable services they consume. Unless a cost-control plan provides for mechanisms that compel cost-benefit trade-offs, it is doomed to failure. Pretending otherwise may seem like good politics, but it is terrible policy.

The National Health System Myth

The United States spends far more on health care than any other country—in fact, more than 50 percent more per capita than the next runners-up, Norway and Switzerland. Yet when we look at basic health indicators such as life expectancy at birth, our performance is the worst in the developed world. The understandable reaction is: If other developed countries are spending so much less on health care and getting better results, why can’t we? The answer is that perhaps we could, but that doing so will not be as simple or as painless as the international comparisons seem to imply.

To begin with, the dismal U.S. ranking on life expectancy has little to do with the inefficiency of the U.S. health-care system, vast as that might be. U.S. survival rates for most chronic diseases, including cardiovascular disease and most cancers, are among the highest in the world—which should hardly be surprising since we are the leading generator of medical R&D and technology for the world. The main reason that the United States has a lower life expectancy than other developed countries is that it has a much higher incidence of chronic morbidity, mostly related to unhealthy lifestyles. In other words, the problem is not that more sick Americans die, but that more Americans get sick. Consider just a few statistics. The United States has the third highest obesity rate in the OECD (only Mexico and Chile are higher) and the third highest incidence of diabetes (only Mexico and Turkey are higher). As for substance abuse, the U.S. opioid-related death rate is not only the highest in the OECD, but is at least double that of every other member country except Canada and Estonia.[3] Changing how the U.S. health-care system is structured and financed would in and of itself do little to improve this picture.

As for cost, it is true that countries with national health systems spend far less on administration than the United States does, something that proponents of the single-payer model often stress. In this respect, at least, one could argue that these systems achieve substantial savings by eliminating pure waste. But lower administrative costs are just one reason that countries with national health systems spend less than we do, and not the most important one. Most developed countries also set overall budgets for government health-care spending and enforce those budgets through some combination of global and/or clinical budget ceilings, provider rate caps, service volume limits, and the application of cost-effectiveness analysis. Some of the savings is achieved by limiting provider incomes. But some is also achieved by limiting patient services—or, in other words, by rationing care. The rationing may be explicit, as when age limits are set for certain procedures. More often it is implicit and comes in the form of waiting lists and ad hoc triage as providers try to make the best use of limited resources.

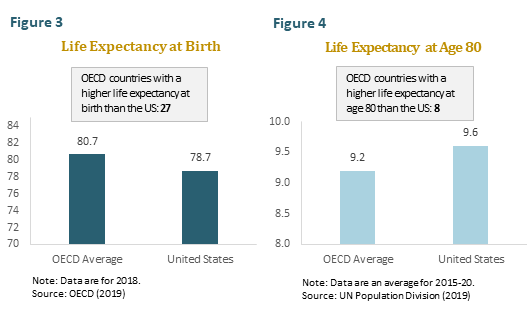

Our purpose is not to criticize national health systems, which have much to recommend them. It is simply to point out that the cost savings they achieve is not all painless. One reason that the United States spends so much more than countries with national health systems is that we perform more elective procedures, from hip replacements to cosmetic surgery. Such procedures do nothing to increase life expectancy, but may nonetheless have a large impact on quality of life. Another reason is that we are more likely to treat disease aggressively late in life. This may help to explain why the United States, though it has a lower life expectancy at birth than any other developed country, has one of the highest life expectancies at age 80. (See figures 3 and 4.) In short, the real lesson to be learned from the international comparisons is that, with or without a national health system, effective cost control always entails trade-offs.

The Comprehensive Reform Myth

It is often asserted that federal health benefit spending can only be efficiently and fairly controlled as part of a comprehensive public-private solution. The core of the argument is that, since the same hospitals and doctors serve both public and private patients, we cannot change the price and treatment style for one group without also changing it for the other. If we try to control federal health benefit spending without also reining in private spending, we will either undermine the quality and availability of health-care services for federal beneficiaries or cause providers to shift costs to private payers, leaving total national health-care spending unchanged.

While this argument raises legitimate concerns, it overlooks a few critically important facts. To begin with, it ignores the federal government’s market clout. If the federal government were just another small purchaser of health-care services, it is true that it could not reduce reimbursement rates while guaranteeing the quality and availability of services for beneficiaries. But in fact the federal government is a massive purchaser that now finances 35 percent of total U.S. health-care spending. This vast market share gives it an extensive—and largely underutilized—power to influence the price, quality, availability, and delivery of health care, both public and private, as well as to restructure medical practice around outcomes analysis, best-practice guidelines, care management, wellness programs, digital records, and all the other sound practices long advocated by health policy reformers. Then there is the influence that the federal government can wield over private prices through its tax and regulatory policies. If private demand needs to be constrained in order to limit cost shifting, the federal government could make an important start by enacting a significant cut in the tax expenditure for employer-paid health care, a regressive subsidy to private health-care consumers that now totals roughly $350 billion a year.

The bottom line is that there are many effective ways to control federal health benefit spending efficiently and fairly without resorting to a comprehensive public-private solution. Insisting that we should wait for one, moreover, has very real drawbacks. It delays federal cost control, perhaps indefinitely, since it must now depend upon political agreement on a much wider variety of issues. It sends the wrong message to an American public whose understanding of comprehensive health-care reform has everything to do with benefit expansions and nothing to do with federal cost constraint. Finally, and most damningly, it ignores a critical distinction between publicly and privately financed health care. Private care is paid for today by private payers, typically the patients themselves or their employers, while a substantial share of public care will be paid for tomorrow by younger and future generations—either through Treasury debt that they will someday have to repay or through unfunded liabilities that must be subtracted from their future living standards. In this sense, Medicare spending has more in common with Social Security spending than with Blue Cross and Blue Shield.

There may of course be a deeper political calculus at work here. Many advocates of a comprehensive public-private solution favor moving the United States toward a national health system, and may believe that there is no point in trying to control federal health benefit spending now, since once such a system is in place cost control will be easy. But whatever the advantages of the single-payer model, painless cost control is not one. Yes, it may make it easier for the federal government to tighten the screws if it is financing all health care. Then again, to judge by Congress’ failure over many decades to control the cost of our existing health benefit programs, it may make it harder. In any case, it will do nothing to change the difficult trade-offs that must ultimately be faced.

The Painful Prescription

Too often in the health-care debate, both policymakers and policy experts have insisted on pretending that cost-benefit trade-offs are unnecessary. It is time we acknowledged that they are essential. Effective cost control will require some people to give up some care that is potentially beneficial—what Brookings economist Henry Aaron has called the “painful prescription.”[1] Once this is acknowledged we can begin to engage the real debate, which is about how best to set limits.

To be sure, identifying and eliminating waste and inefficiency must be a key part of any long-term cost control strategy. But let’s be realistic. Most patients today are shielded from the full cost of their health-care decisions by third-party payment systems, and so have little incentive to care about the quantity or price of the services they consume. Most physicians are paid on a fee-for-service basis, and so have every incentive to increase the quantity and price of the services they provide. Add to this massive open-ended federal subsidies, barriers to interstate competition among medical providers and insurers, and a malpractice system that encourages defensive medicine, and it’s both feet on the health-cost accelerator.

In the end, America will have no choice but to restrain the growth in federal health benefit spending. The place to start is for the federal government to create a global budget with annual targets for what it spends on health care, just as governments in many other developed countries do. In enforcing this budget, we could move in one of two directions. The first is toward top-down rationing implemented by imposing price and volume controls and by dictating best practice. The second is toward a wholesale restructuring of our health-care system’s cost-plus incentives. Here the surest approach would be to capitate Medicare and Medicaid—that is, to replace today’s open-ended payment promises with a system of “premium support” consisting of fixed-dollar subsidies that beneficiaries would use to purchase insurance. Whichever direction we move in, there would have to be a “look back” mechanism to guarantee that savings are later recouped if spending levels exceed the annual targets.

Although top-down rationing works well in many other developed countries, in our political culture it may meet with considerable resistance from the public. It is one thing for the federal government to research and publish best practice guidelines. It would be another thing entirely for it to dictate in detail what sorts of care providers can and cannot deliver to their patients. Moving toward capitation would have the virtue of leaving decision-making in the hands of patients and providers, and is likely to result in a more efficient allocation of resources. But let there be no doubt: It too will require sacrifice. And it too will require overcoming the resistance of a gigantic health-care industrial establishment, buttressed by literally hundreds of organized lobbies and buoyed by the do-everything expectations of the public.

Whatever shape reform takes, our aging society will not be able to escape the difficult ethical and moral questions that imposing limits raises. At the micro level, we will need to consider how much to spend on testing for low-probability risks and how much to spend on attempting low-probability cures. At the macro level, we will have to face the biggest trade-off of all—how much do we tax our children and grandchildren to extend our own lives and how much do we leave for those who will live beyond us. We do not claim to have the answers to these questions. But our leaders must stop pretending they can finesse them. The longer we wait to decide the more difficult the choices will become.

Resources

22-0211_GAI-Concord Issue Brief 4

Footnotes

[1] Henry J Aaron and William B. Schwartz, The Painful Prescription: Rationing Hospital Care (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1984).

[1] The CBO assumes that in the long run excess cost growth will fall to just 1.0 percent per year. Although excess cost growth has historically exhibited considerable volatility, even turning negative at times, according to the CMS Office of the Actuary it averaged 1.5 percent per year between 1975 and 2018, and for most of that period was running at 2.0 percent per year or higher. See Stephen K. Heffler et al., “The Long-Term Projection Assumptions for Medicare and Aggregate National Health Expenditures,” CMS Office of the Actuary memo, April 22, 2020, available at https://www.cms.gov/files/document/long-term-projection-assumptions-medicare-and-aggregate-national-health-expenditures.pdf.

[2] The Dartmouth Health Atlas Project has been publishing research on medical practice variation in the United States since 1996. The research is available at https://www.dartmouthatlas.org/.

[3] For the data on survival rates, morbidity, and lifestyle-related risk factors, see Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators (Paris: OECD, 2019). For an excellent discussion of the factors explaining cross-country differences in life expectancy, see Samuel H. Preston and Jessica Ho, “Low Life Expectancy in the United States: Is the Health Care System at Fault?” in International Differences in Mortality at Older Ages: Dimensions and Sources, eds. Eileen M. Crimmins, Samuel H. Preston, and Barney Cohen (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2010).

Continue Reading