It seems that immigration is never out of the news these days. There is of course the crisis triggered by the surge in asylum seekers arriving at the southern border. There is the backlog of refugee applications. And there is the contentious debate over policy issues that never seem to be resolved, from how best or even whether to secure the southern border to how best or whether to offer a path to citizenship to unauthorized immigrants who are already here, and especially the so-called Dreamers.

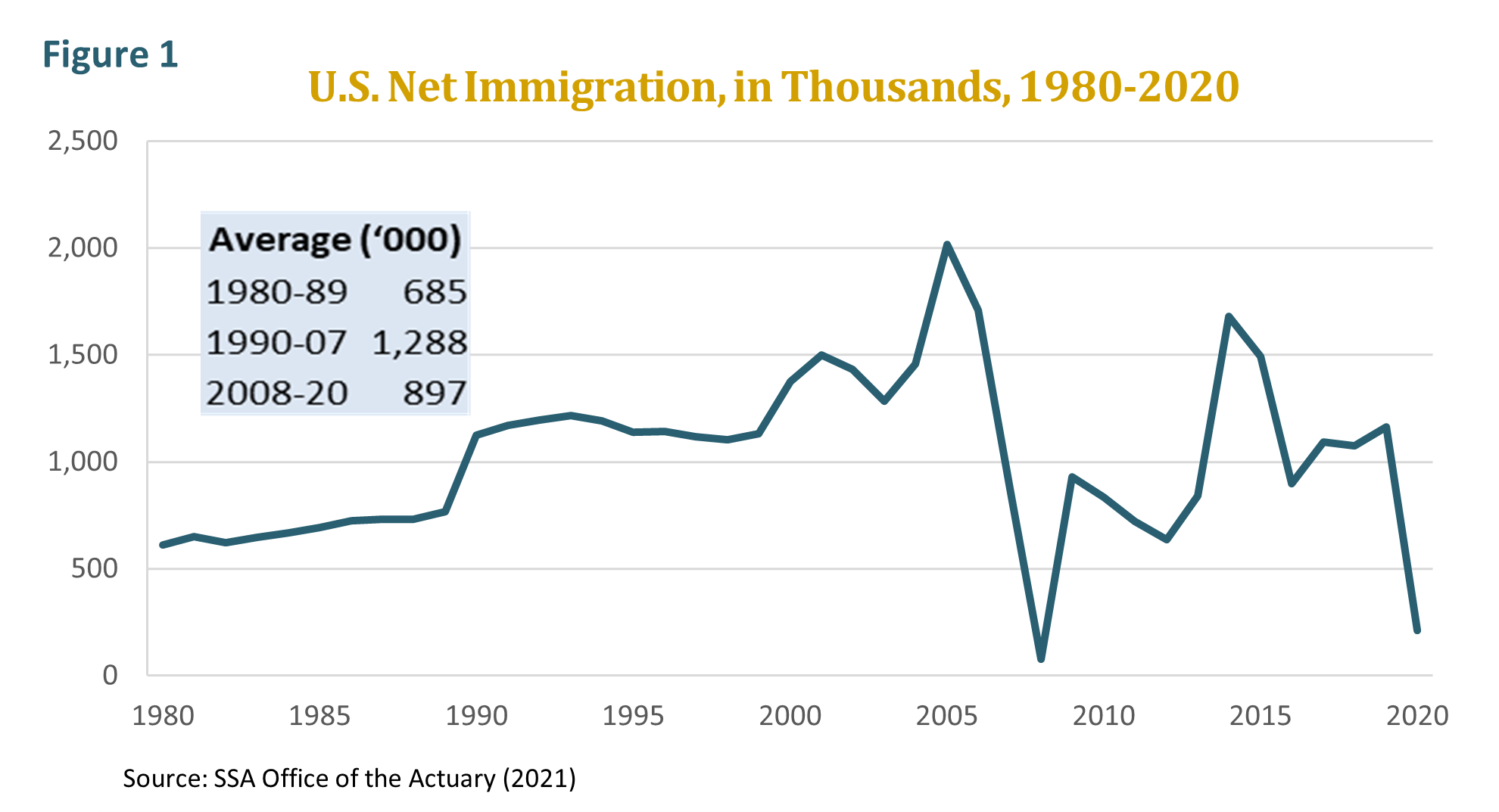

Lost in all of this is any sense of the bigger picture. You would never know from the current debate that net immigration has actually been declining, from an average of 1.3 million per year from 1990 to 2007 and the beginning of the Great Recession to 0.9 million per year since then.[1] Nor would you know that, even as immigration has been declining, its importance to demographic and economic growth has been increasing. With the large Boomer generation retiring and relatively smaller generations taking its place, immigration is already the only reason that the United States still has a growing workforce. By the 2040s, it will be the only reason that the United States still has a growing population.

America’s story can in large part be told as a story of immigrants. Yet as important as immigration has always been in shaping America’s character and culture, it has never been as critical to growth and prosperity as it will be in coming decades. Several developed countries, most notably Australia and Canada, have made immigration the lynchpin of their long-term strategy for confronting population aging. Meanwhile, the United States continues to lurch from near-term crisis to near-term crisis.

The purpose of this issue brief is to place immigration within the broader context of America’s changing demographics and to explain why the country needs more of it, not less. Along the way, we attempt to clear up a number of widespread misconceptions about the costs and benefits of immigration that distort the current debate. However, we do not take positions on specific policy issues, much less offer a comprehensive immigration reform plan. We recognize that there is more than one way to reform the system so that it better serves America’s needs. What’s critical is that policymakers engage the challenge.

A More Typical Developed Country

America finds itself at a demographic crossroads. Until recently, the United States was a demographic outlier among its developed world peers. After dipping well beneath the 2.1 replacement rate needed to maintain a stable population from one generation to the next in the 1970s, the U.S. total fertility rate partially recovered as Boomers finally got around to starting families. From the beginning of the 1990s until the Great Recession, it averaged 2.0, higher than the average for any other developed country except Iceland, Israel, and New Zealand. Together with substantial net immigration, America’s relatively high fertility rate seemed to ensure that it would remain the youngest of the major developed countries for the foreseeable future. It also seemed to ensure that America would still have a growing workforce, even as those in other developed countries stagnated or declined.

Over the past decade, however, America has begun to look much more like a typical developed country. The U.S. total fertility rate began to decline in 2008 and, except for a minor uptick in 2014, has fallen every year since. By 2019, on the eve of the pandemic, it had dropped to 1.7, an all-time historical low. Now the pandemic has driven it even lower, to 1.6 in 2020 and perhaps to as low as 1.5 in 2021. At the same time net immigration—that is, the number of immigrants minus the number of emigrants—has also declined. After rising during the 1990s and early 2000s, it sank to near zero in 2008 during the depths of the Great Recession. Since then net immigration has followed a roller-coaster path. It experienced a partial recovery in the early 2010s, but began to decline again starting in 2015. The decline then became a plunge in 2020 as immigration was dramatically curtailed amid the pandemic-related border closings. (See figure 1.)

Initially, many demographers assumed that Millennials, like Boomers before them, were merely postponing family formation rather than deciding to have fewer children, and that the total fertility rate would soon begin rising again. But the oldest Millennials are now turning 40, and there is still no sign of this “tempo effect.” Although some post-pandemic recovery in birthrates is possible, a return to the substantially higher levels of the 1990s and early 2000s seems increasingly unlikely unless the longer-term developments that have depressed birthrates are reversed. The most important of these is that it has become much more difficult for Millennials to launch careers and establish independent households than it was for Boomers or Gen-Xers at the same age.

With the prospects for a recovery in fertility at best uncertain, increasing immigration becomes all the more important. Fortunately, it is much easier to increase immigration than it is to increase fertility. To be sure, some of the developments that have depressed immigration since the Great Recession, like the developments that have depressed birthrates, may prove to be enduring. These include slower population growth in Latin America (less immigration “push”) and slower economic growth in the United States (less immigration “pull”). But there are other regions of the world in which populations are still growing rapidly, including South Asia and Africa. Immigration is also highly responsive to policy, and policy can be made less restrictive.

There is considerable room for principled disagreement on matters of immigration policy, from whether there should be a path to citizenship for unauthorized immigrants to whether our current system, which is primarily based on family reunification, should be replaced with a skills-based system. What is not in question is that an aging America would benefit from increased immigration. In the past, when we had replacement-level fertility, immigrants were what kept the workforce growing. In the future, they will be all that keeps it from shrinking.

An Indispensable Key to Growth

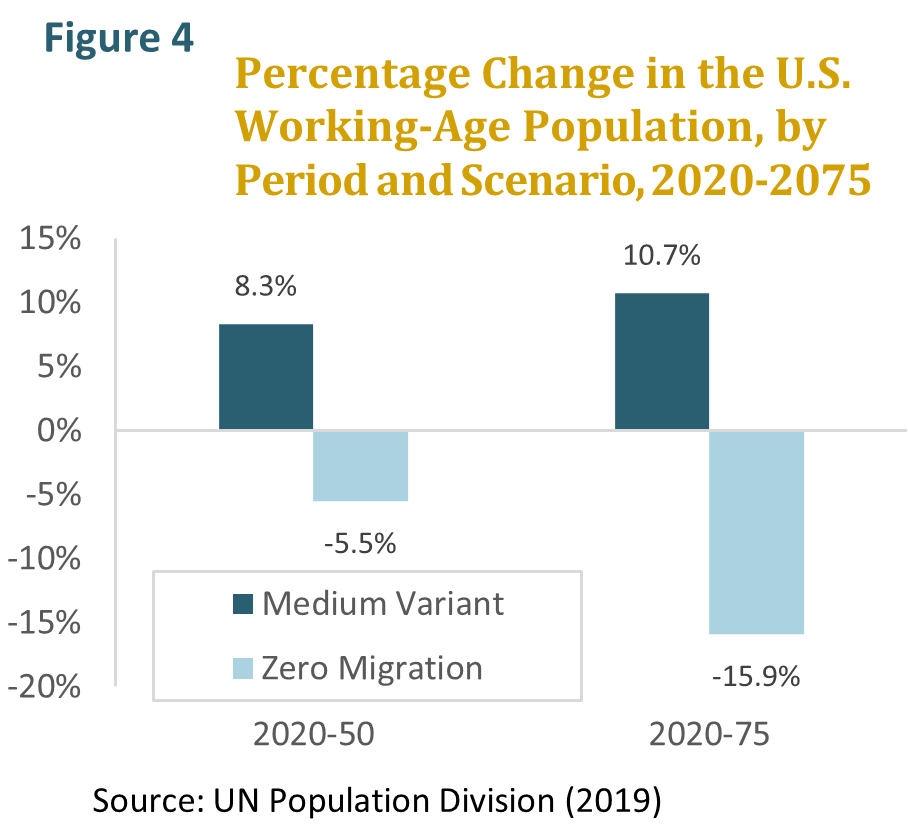

Growth in the working-age population, and hence employment, has always been an important driver, and sometimes the most important driver, of economic growth in the United States. But as the smaller cohorts born since the end of the postwar Baby Boom have climbed the age ladder, growth in the working-age population has been decelerating, from 1.7 percent per year in the 1970s to 0.7 percent per year since 2000. Over the next three decades, according to the CBO’s latest March 2021 long-term projections, the working-age population will be growing at an average rate of just 0.2 percent per year. All of this growth, moreover, will be attributable to net immigration, which the CBO assumes will gradually climb from its 2021 level of about 500,000 to between 1.0 and 1.1 million per year, significantly more than its average since the Great Recession. Without net immigration, the working-age population would actually shrink. (See figure 2.)

GDP growth of course has two components: employment growth and productivity growth. Immigration obviously increases the first, not just because immigrants add to the total population, but also because they are more likely to be of working age than the native-born population. Although the dynamics are more complicated, most economists believe that immigration also increases productivity growth. For one thing, the faster employment growth that comes with immigration increases the need for capital-broadening investment, and higher rates of investment, and consequently a more rapid turnover in the capital stock, can spur technological progress by increasing opportunities for “learning by doing.” For another, numerous empirical studies have found that the greater diversity of skills and entrepreneurial initiative that immigrants bring to the economy also spur productivity growth. Indeed, the boost that immigration gives to economic growth by increasing productivity may be even more important than the boost it gives by increasing employment.[2]

All of this helps to explain why immigration is an indispensable key to maintaining economic growth in an aging America. Even with the substantial level of net immigration that the CBO projects, real GDP growth will sink to just 1.5 percent per year in the 2030s and 2040s, barely one-half of its postwar average. If net immigration fails to rise back to the level that the CBO projects, the economic outlook would be even worse. On the other hand, if net immigration exceeds the level that the CBO projects, the economic outlook could be considerably better.

Common Concerns

The potential economic advantages of immigration are widely recognized by economists. Indeed, it would be difficult to find one who does not agree that aging societies with slowly growing or contracting workforces would benefit from more of it. Nonetheless, a number of common but largely misplaced concerns about the costs and benefits of immigration continue to distort the policy debate.

Perhaps the most frequently heard is that immigrants take jobs from native-born workers. This is of course possible at the firm level, and may even be possible at the industry level. But at the economywide level virtually all economists agree that the notion there is a zero-sum competition between different groups for the jobs that the economy creates is groundless. They even have a name for it: the “lump of labor fallacy.” The truth is that jobs for immigrant workers do not deny jobs to native-born workers any more than jobs for women deny jobs to men or jobs for the old deny jobs to the young. In fact, just the opposite is true. The jobs that immigrants take generate additional income, resulting in additional demand for goods and services that in turn translates into additional jobs. At the economywide level, immigration is a positive-sum proposition.

It is true that, to the extent immigrants and native-born workers have similar skill sets, competition between them could lower wages. Most studies, however, have concluded that the impact is generally small and diminishes over time.[3] The focus on wage competition between immigrants and native-born workers with similar skill sets, moreover, overlooks the considerable increase in economic and social welfare that can occur when immigrants and native-born workers have complementary skill sets. A much larger share of foreign-born adults aged 25 and over have less than a high school degree than native-born adults (27 percent versus 8 percent in 2018), which means that they tend to take low-skilled but necessary jobs that most native-born adults do not want. At the other end of the labor-market spectrum, many immigrants are highly educated. Indeed, the share of foreign-born adults aged 25 and over with a four-year college degree or more (32 percent) is virtually identical to the share of native-born adults with one (33 percent). Whether as nurses and doctors or engineers and IT professionals, these immigrants provide services that benefit all Americans, and especially the majority who are less educated.

Another frequently heard concern is that immigrants consume more in government benefits than they pay in taxes, and thus constitute a burden on native-born workers and taxpayers. The question of whether immigrants are net fiscal beneficiaries or net fiscal contributors is admittedly a complex one, but most of the evidence suggests that the fear they are free riders on the social safety net is mostly unfounded. Yes, some studies have concluded that immigrants usually increase the burden on state and local government budgets. One reason is that immigrants on average have larger families than native-born adults, and are therefore disproportionate consumers of educational services. Another is that immigrants on average have lower incomes, and therefore pay less in state and local taxes. Many other studies, however, have concluded that at the federal level the net balance of taxes paid and benefits received tilts the other way, in part because immigrants are less likely than native-born adults to qualify for federal benefit programs and in part because the federal tax system, due to its greater progressivity, raises more revenue from higher-income immigrants than state and local tax systems do. Almost all studies, moreover, have concluded that if we take a generational perspective and include the future tax contributions of immigrants’ children, the net fiscal impact of immigration is clearly positive.[4]

Other concerns center around the perception that recent waves of immigrants are failing to assimilate as readily as earlier waves did. A country’s success at integrating immigrants is clearly important. Indeed, when integration falters or fails the costs of immigration, both economic and social, can easily outweigh the benefits. This is a significant problem in many European and Asian societies, which do not have America’s long history as a “melting pot.” But it does not appear to be a problem here. Consider just a few indicators. Overall, foreign-born adults have a higher labor-force participation rate than native-born adults, and foreign-born men have a much higher participation rate. While only a slight majority of immigrants speak English proficiently, virtually all of their native-born children do. When it comes to their grandchildren, moreover, not only do virtually all speak English proficiently, virtually none speak their grandparents’ native language at all. The self-identification of immigrants shows a similar evolution from generation to generation—from, for instance, Mexican, to Mexican-American, to just plain American.[5]

Then there are the concerns about illegal immigration, which many Americans incorrectly assume constitutes most of total immigration. Illegal immigration did surge in the 1990s and early 2000s. But it fell sharply during the Great Recession as more unauthorized immigrants began returning to Mexico than were arriving from there. Since then, according to most estimates, the number of unauthorized immigrants living in the United States has stabilized at around 10 to 11 million, or 3 percent of the population. This is not to say that illegal immigration is not a problem. Every sovereign nation has a compelling interest in securing its borders and ensuring that its laws are observed. But it is important to recognize that as of 2017, the latest year for which data are available, 77 percent of the foreign-born population in the United States was here legally, and that of the 23 percent which was not two-thirds had lived here for at least ten years.

It is also important to recognize that, at least in relative terms, the foreign-born population of the United States is not uniquely or even unusually large. It is true that, in absolute numbers, the United States has a larger foreign-born population than any other country in the world. It is also true that the foreign-born share of the U.S. population has been rising steadily in recent decades, climbing from an historical nadir of 4.7 percent in 1970 to 13.6 percent in 2019, almost as high as the share in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, when Ellis Island was the gateway for the last great wave of European migration to America. But many developed countries have comparable or higher rates of net immigration, and in many the foreign-born population makes up a share of the total population that is nearly as large or even larger than it is here. (See figure 3.)

A Nation of Immigrants

It is difficult to imagine how an aging America can be a prosperous America without the impetus to growth and the promise of renewal that immigration brings. We believe that, at a minimum, public policy should seek to ensure that net immigration increases to the 1.0 to 1.1 million level that is already assumed in the latest CBO long-term projections. Even better, it should seek to ensure that net immigration increases to something closer to its 1.3 million average in the late 1990s and early 2000s. But we recognize that there is room for debate about these targets, and that there is no “magic number.”

We also recognize that there is room for debate about how best to structure the immigration system. If maximizing economic growth is the primary goal, a strong case can be made for shifting from our current system based on family reunification to a skills-based system.[6] Australia and Canada, which have made immigration central to their strategies for confronting population aging, have “points systems” that admit most immigrants based on such factors as educational attainment, language mastery, and work experience. The idea is not to have government determine the specific skills that the economy needs, but rather to identify and admit those immigrants deemed likely to be the most productive contributors to the economy. Defenders of the current system, however, could reasonably counter that where one starts out in life does not necessarily determine where one ends up, and that generations of immigrants to America have demonstrated that ambition and hard work may be more important to success than credentials or experience.

Whatever type of system we have, higher immigration cannot reverse the aging of the population or solve all of the challenges that it poses. It is true that immigrants, because they tend to be younger on average than the native-born population, can slow the pace of population aging. But immigrants have the unfortunate habit of growing old in their turn, which means that, unless an increase in immigration is both very large and continuously rising over time, it will not greatly alter the long-term age structure of the population. A good way to illustrate this point is to compare the UN Population Division’s medium variant projection, which assumes a similar level of immigration to the CBO projection, with its zero migration variant, which, as its name suggests, assumes there will be no additional immigration in the future. With immigration, the UN projects that the elderly share of the U.S. population will grow to 22.4 percent in 2050, while without immigration it would grow to 24.5 percent. Immigration helps, but only marginally.

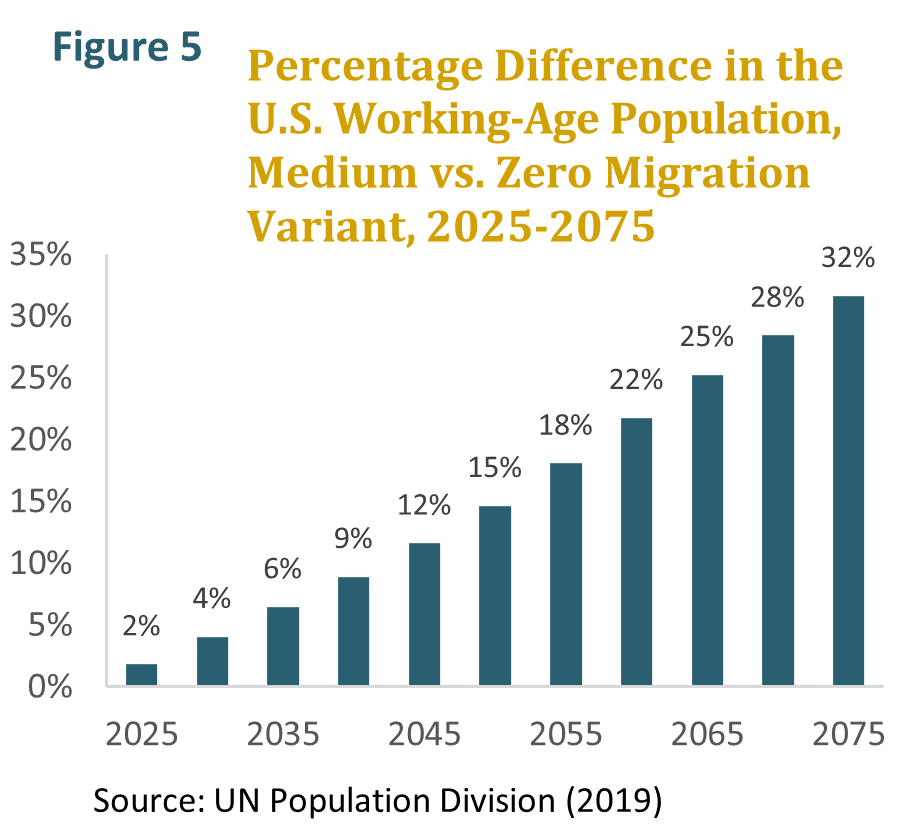

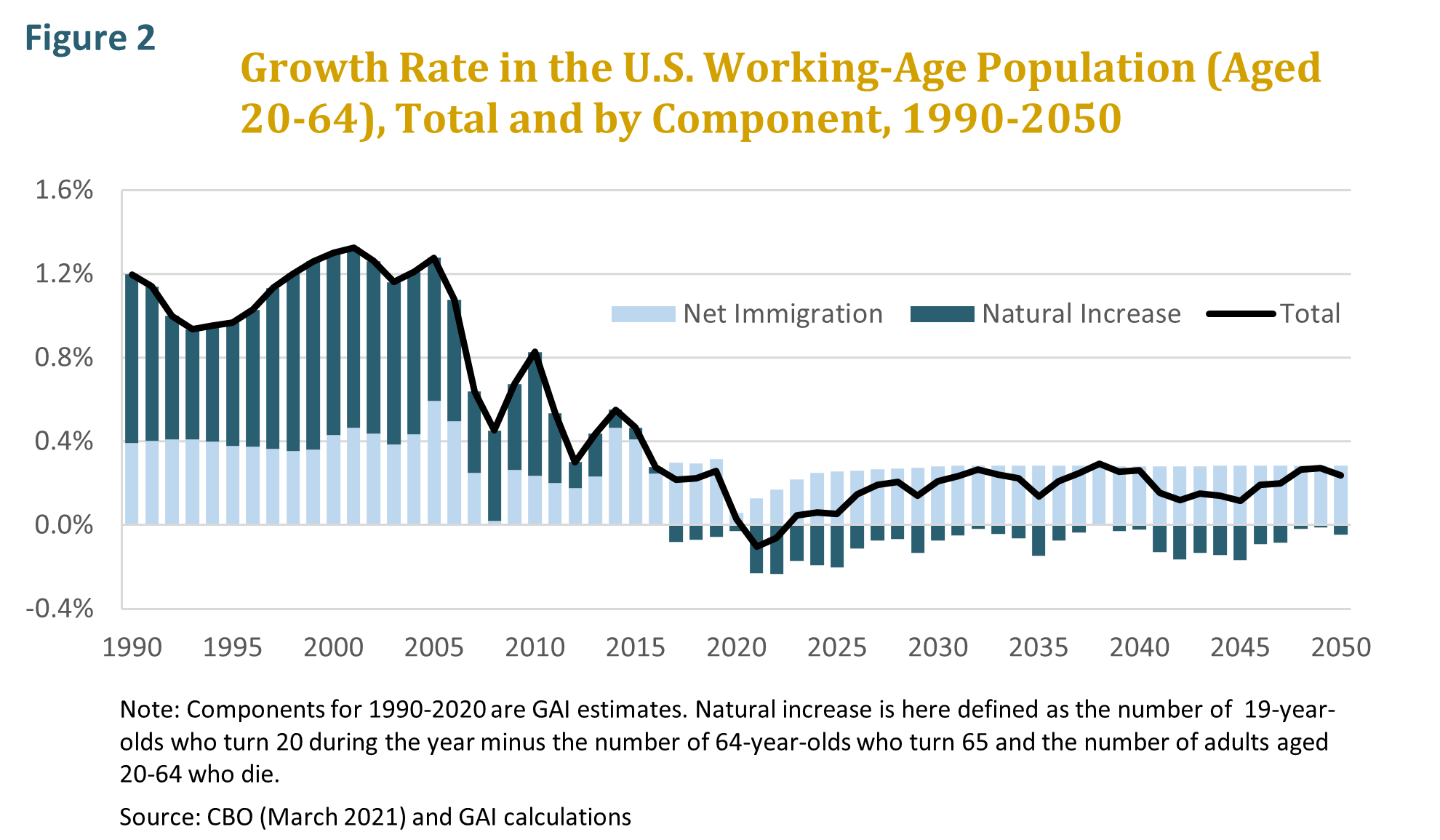

Where immigration can have a large impact is in increasing the growth rate in the working-age population, and hence the growth rate in employment and GDP. Once again, consider the two UN projection scenarios. In its medium variant, the UN projects that the working-age population will grow by 8.3 percent between 2020 and 2050, while in its zero migration variant it projects that it will shrink by 5.5 percent. The advantage of immigration, moreover, continues to compound over time. By 2075, the working-age population will have grown by 10.7 percent with immigration but shrunk by 15.9 percent without it. To look at the numbers another way, by 2075 the working-age population would be one-third larger with immigration than without it. (See figures 4 and 5.) All other things being equal, GDP would also be one-third larger—and a larger GDP in turn makes all things more affordable, including paying for the cost of our aging society.

Although there are other ways that America could boost economic growth, none of them are as certain as increasing immigration. More fully taping the productive potential of the elderly, who are not only America’s most underutilized human resource but also the fastest growing segment of its population, could help a great deal. But after rising steadily over the past two decades, elderly labor-force participation plunged during the pandemic, and it is uncertain whether it will recover. In any case, as the large Boomer cohorts age into their seventies, eighties, and nineties, the potential boost to employment from “productive aging” will diminish. Increasing the labor-force participation of younger adults, which has fallen since the Great Recession, would also help. But younger adults already work at a much higher rate than older adults do and, moreover, will be a shrinking share of the population. As for higher productivity growth, which some might hope could substitute for higher employment growth, there is little reason to expect a sudden surge. Indeed, productivity growth is more likely to fall than to rise in an aging America, which may have lower rates of investment, an aging capital stock, and a less entrepreneurial workforce.

Higher birthrates could also make a large difference. Raising them, however, will not be easy. Policy initiatives that mitigate the costs of childrearing and help young adults to balance job and family responsibilities might help. But such policies are expensive, and the evidence from other developed countries suggests that their impact on birthrates is generally modest. Even if birthrates were to surge overnight, moreover, it would not have an appreciable effect on the growth rate in employment or the ratio of workers to retirees for another twenty to twenty-five years, the time it takes for a newborn baby to become a fully productive adult. For their part, immigrants arrive ready to work.

Today’s sometimes contentious debate over immigration notwithstanding, most Americans have positive views about immigrants. According to a recent Pew Research Center survey, two-thirds of Americans say that immigrants strengthen the country “because of their hard work and talents,” while just one-quarter say that they burden it. The share of Americans holding this positive view, moreover, has risen dramatically in recent years, from 31 percent in 1994 to 66 percent in 2019. Meanwhile, the share of Americans saying that legal immigration should be decreased has fallen from 53 percent in 2001 to 24 percent in 2018, while the share saying that it should be increased has risen from 10 to 32 percent.[7]

Resources

21-1205_GAI-Concord Issue Brief 3_0

About the Global Aging Institute

The Global Aging Institute (GAI) is a nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to improving our understanding of global aging, to informing policymakers and the public about the challenges it poses, and to encouraging timely and constructive reform. GAI’s agenda is broad, encompassing everything from retirement security to national security, and its horizons are global, extending to aging societies worldwide.

GAI was founded in 2014 and is headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia. Although GAI is relatively new, its mission is not. Before launching the institute, Richard Jackson, GAI’s president, directed a research program on global aging at the Center for Strategic and International Studies which, over a span of fifteen years, played a leading role in shaping the debate over what promises to be one of the defining challenges of the twenty-first century. GAI’s Board of Directors is chaired by Thomas S. Terry, who is CEO of the Terry Group and past president of the International Actuarial Association and the American Academy of Actuaries. To learn more about GAI, visit us at www.GlobalAgingInstitute.org.

About The Concord Coalition

The Concord Coalition is a nationwide, non-partisan, grassroots organization advocating generationally responsible fiscal policy. It was founded in 1992 by former Senator Paul E. Tsongas (D-Mass.), former Senator Warren B. Rudman (R-N.H.), and former U.S. Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson with a non-partisan mission to confront the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges and build a sound economy for future generations. The Concord Coalition’s national field staff, policy staff, and volunteers carry out the organization’s public education mission throughout the nation.

Footnotes

[1] Most data in this issue brief come from standard government and multilateral sources, including the Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), the U.S. Census Bureau, the Congressional Budget Office (CBO), the Social Security Administration (SSA), the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD), and the UN Population Division. Some data also come from the Pew Research Center and the Migration Policy Institute.

[2] See, among others, The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration (Washington, DC: The National Academies Press, 2017), 279-319; Florence Jaumotte, Ksenia Koloskova, and Sweta C. Saxena, “Impact of Migration on Income Levels in Advanced Economies,” Spillover Note 8 (Washington, DC: IMF, October 2016); and Giovanni Peri, “The Effect of Immigration on Productivity: Evidence from U.S. States,” NBER Working Paper 15507 (Cambridge, MA: NBER, November 2009).

[3] For a review of the literature on the impact of immigration on wages, see The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, 165-278.

[4] For a review of the literature on the fiscal impact of immigration, see The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, The Economic and Fiscal Consequences of Immigration, 323-566 and OECD, International Migration Outlook 2013 (Paris: OECD, 2013), 125-189.

[5] Mark Hugo Lopez, Ana Gonzalez-Barrera, and Gustavo Lopez, “Hispanic Identity Fades across Generations as Immigrant Connections Fall Away” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, December 20, 2017), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2017/12/20/hispanic-identity-fades-across-generations-as-immigrant-connections-fall-away/.

[6] For a discussion of the potential advantages of a skills-based immigration system for the United States, as well as a proposal for creating one, see Douglas Holtz-Eakin and Jacqueline Varas, Building a Pro-Growth Legal Immigration System (Washington, DC: American Action Forum, 2019). The report, which was prepared as part of The Concord Coalition’s “Toward a Fiscally Responsible Economic Growth Agenda” project, is available at https://www.americanactionforum.org/research/building-a-pro-growth-legal-immigration-system/.

[7] See “Key Findings about U.S. Immigrants” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, August 20, 2020), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2020/08/20/key-findings-about-u-s-immigrants/ and “Shifting Public Views on Legal Immigration to the U.S.” (Washington, DC: Pew Research Center, June 28, 2018), available at https://www.pewresearch.org/politics/2018/06/28/shifting-public-views-on-legal-immigration-into-the-u-s/.

Continue Reading