The United States health care system is larger than the gross domestic product of all but five other nations. Over the past several decades, health care costs have outpaced economic growth, inflation and personal incomes. One out of every six dollars of the nation’s annual production of goods and services is now devoted to health care. The implications of health care spending’s continued growth extend beyond traditional health care concerns, such as the availability and delivery of medical services; this growth is a major factor in national economic policy. A consensus exists across ideological and partisan divides that: 1) as a nation, we are not getting what we pay for when we spend as much as we do on health care, and 2) health care spending growth in the United States is on an unsustainable path.

Numerous problems come from such a large, costly and growing health care system. In the private sector, health care costs are eroding companies’ bottom lines. Americans fortunate enough to have employer-sponsored health insurance increasingly are paying more of their premiums or are seeing their wages stagnate as their employers pay higher premiums.

In the public sector, projected cost growth for Medicare and Medicaid is the single largest contributor to our nation’s unsustainable fiscal outlook.

As the search for solutions continues, it seems clear that there is no magic bullet. Adopting policies that simply cut benefits or limit provider payments might leave the system better off in a strictly fiscal sense but could severely reduce access to quality care. Similarly, raising new revenues to fund the current system or expand coverage to more of the uninsured are important but do nothing to control health care inflation over the long term or improve the value of services received. In the end, it will take a mix of strategies to bring health care costs down to a sustainable level while improving quality and value.

Major Federal Health Programs

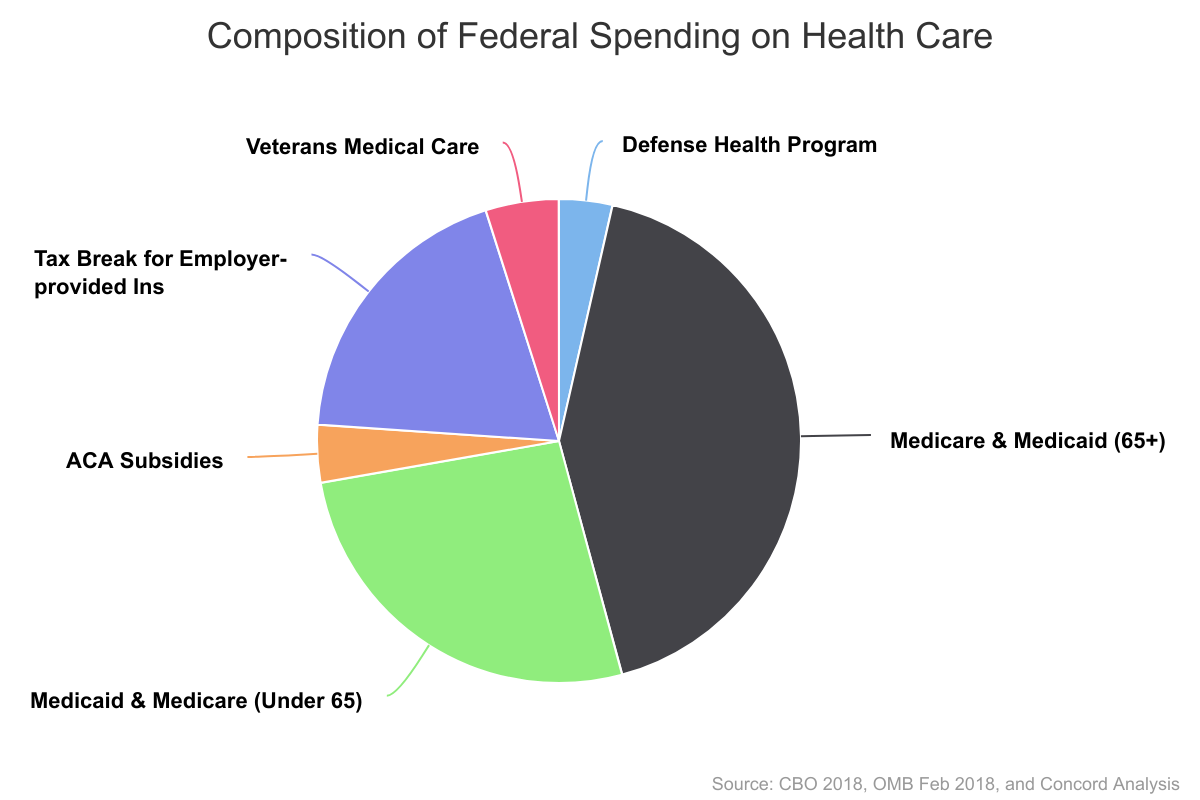

The federal government subsidizes the health care of most American adults in a variety of ways, depending on their age, military service, employment status, income and health. The majority of Americans have employer-based coverage, which is subsidized through preferential tax treatment. Middle- and lower-income individuals who do not have access to employer-provided health insurance are eligible for tax credits under the Affordable Care Act that enable them to purchase individual plans on the private market. The rest of the insured are covered directly through government-run insurance programs.

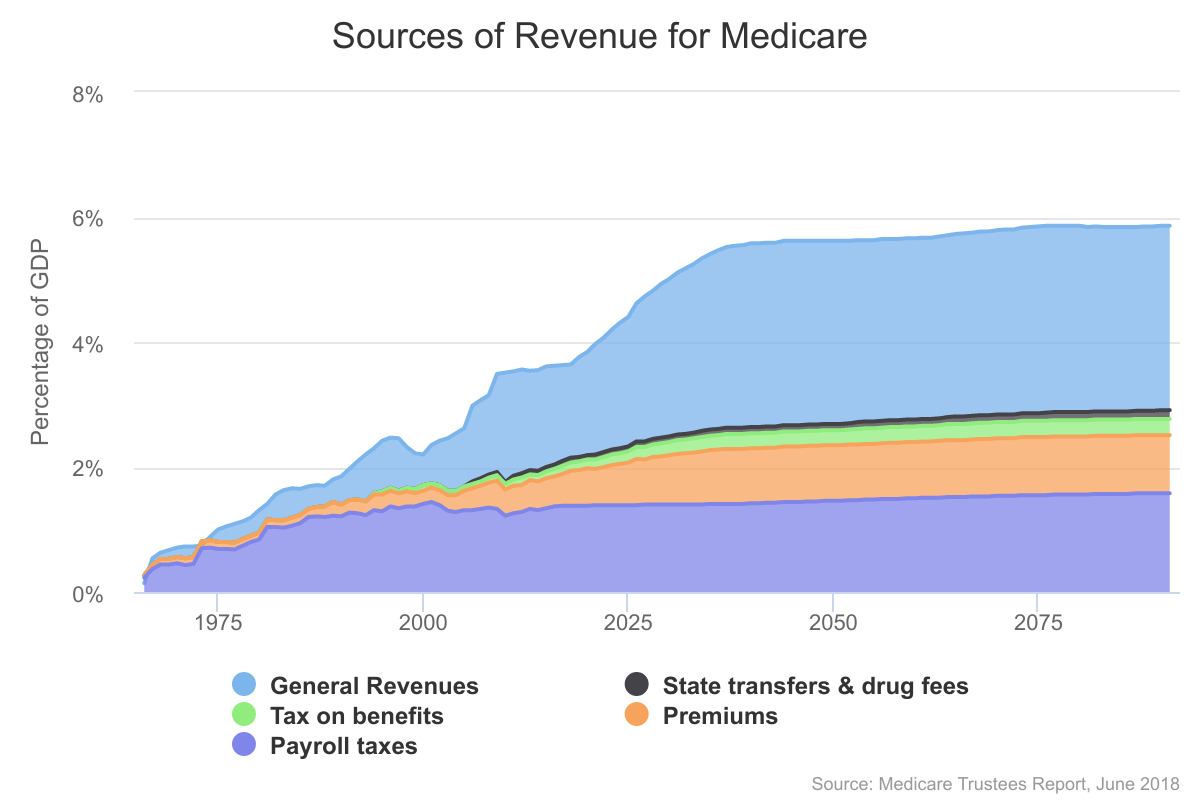

Of these programs, the government spends the most on Medicare. It provides health insurance for nearly all Americans over 65 as well as workers who have become disabled. It is available regardless of income, although higher-income individuals have higher premiums. Medicare has four parts:

- Part A: Hospital Insurance, which is financed by the Medicare payroll taxes on current workers, covers hospital services, post-hospital services and hospice care.

- Part B: Supplementary Medical Insurance, which is financed by premiums that pay for around 25 percent of the program with general federal tax revenues paying the remainder, covers physician services, outpatient hospital care, home health care and medical equipment (optional coverage but most seniors subscribe).

- Part C: Medicare Advantage, which provides private insurance product options for beneficiaries enrolled in Parts A and B.

- Part D: Prescription Drug Coverage, which is financed by general tax revenues and premiums, provides optional prescription drug coverage for older Americans and disabled.

Like Social Security, parts of Medicare have dedicated revenue sources and a trust fund designed to maintain the link between these revenues and program spending. However, because the program relies on general revenue subsidies significantly more than Social Security, these trust funds are of limited value in determining the long-term fiscal health of the program.

The second largest federal health care program in terms of spending is Medicaid although it covers more people than Medicare. Medicaid provides health insurance and long-term care for low-income Americans. While the federal government usually pays more than half of the costs, the program is administered by the states — subject to minimum federal requirements for basic benefits. In states that expanded Medicaid through the Affordable Care Act (ACA), all adults between ages 18 and 65 are eligible for coverage if they have incomes at or below 138 percent of the federal poverty level. In states that chose not to expand Medicaid, to be eligible, individuals must fall into one of the several dozen eligibility categories that divide into three general groups: families with children, elderly people, and people with mental or physical disabilities.

In addition to expanding insurance coverage through Medicaid, the ACA allows individuals and families to purchase private health insurance coverage through state-based health insurance exchanges or marketplaces. Those with certain income levels (roughly between 130 percent of the federal poverty level and 400 percent) are eligible for tax credits to cover portions of their premiums, and they can receive additional subsidies to reduce out-of-pocket cost-sharing expenses.

The federal government also operates a number of smaller health programs. These include the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP), which funds health benefits for children from low-income families, and health programs for members of the military and civilian federal employees.

Long-term Trends

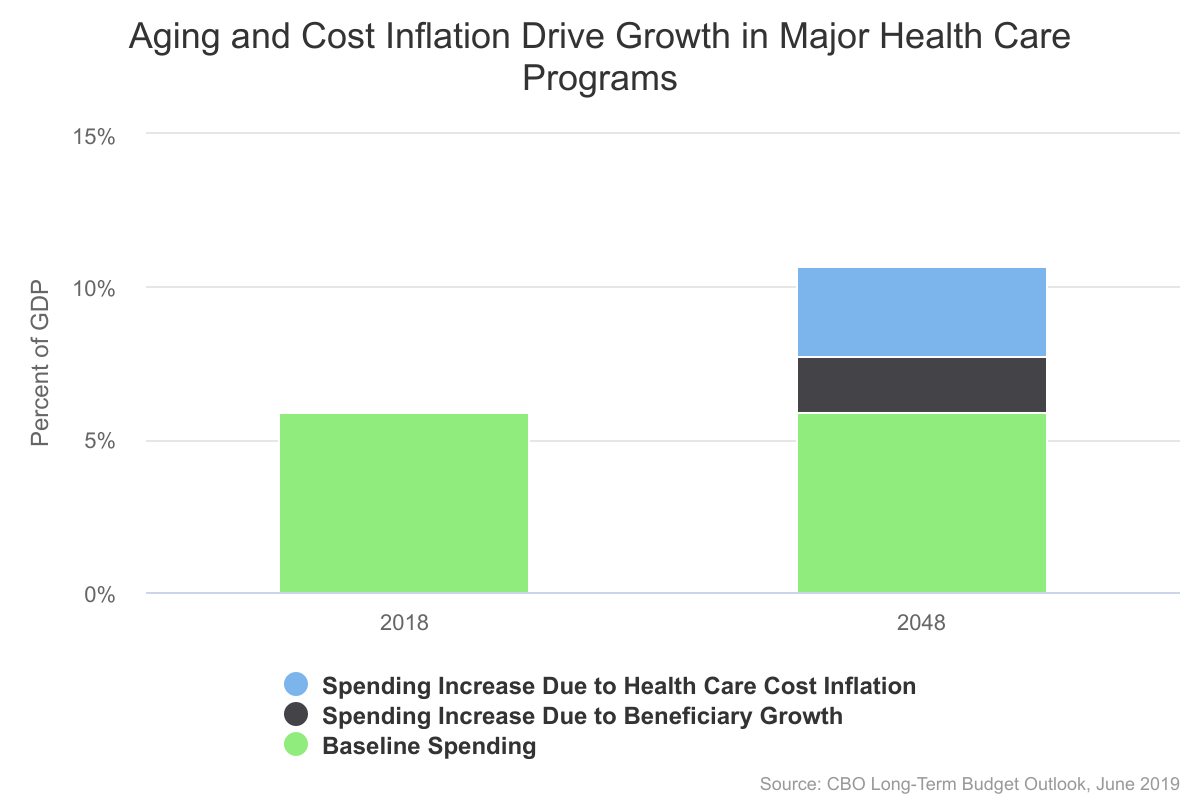

The long-term growth of health care costs has a large impact on the nation’s fiscal sustainability. Increasing numbers of beneficiaries due to the aging of the population alone will increase spending on health care. Cost growth has slowed recently, however the durability of that slowdown is unknown and most health care economists are concerned about cost growth rising in the future.

Nevertheless, there is a fair amount of bipartisan consensus on some steps that still need to be taken to reduce health care cost growth and that the sooner changes are made, the quicker we can make the health care system more efficient and even improve health while doing so. Finally, acting sooner rather than later means a better chance of holding down federal debt levels, encouraging economic growth and improving living standards.