Table 1. President’s Budget for FY 2008

| Actual |

Estimated |

|||||||

| 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

||

| In billions of dollars |

||||||||

| Receipts |

2,407.3 |

2,540.1 |

2,662.5 |

2,798.3 |

2,954.7 |

3,103.6 |

3,307.3 |

|

| Outlays |

2,655.4 |

2,784.3 |

2,901.9 |

2,985.5 |

3,049.1 |

3,157.3 |

3,246.3 |

|

| Deficit (-)/Surplus |

-248.2 |

-244.2 |

-239.4 |

-187.2 |

-94.4 |

-53.8 |

61.0 |

|

| As a percent of GDP |

||||||||

| Receipts |

18.4% |

18.5% |

18.3% |

18.3% |

18.3% |

18.3% |

18.6% |

|

| Outlays |

20.3% |

20.2% |

20.0% |

19.5% |

18.9% |

18.6% |

18.3% |

|

| Deficit (-)/Surplus |

-1.9% |

-1.8% |

-1.6% |

-1.2% |

-0.6% |

-0.3% |

0.3% |

|

Source: Office of Management and Budget (OMB), The Budget for Fiscal Year 2008.II. The five-year budget (FY 2008-2012)

II The five-year budget (FY2008-2012)

The proposal does seek, however, to deny to future presidents and congresses the flexibility they will need to address impending budget challenges. The latest, and effectively last, budget of the current Bush Administration is its first presented to a Congress controlled by Democrats.[2] While the administration and Congress are likely to have different priorities, they share a common goal of balancing the budget by 2012 and a recognition that long-term fiscal policy is unsustainable. Progress cannot be made on either front with proposals that only appeal to narrow partisan interests.

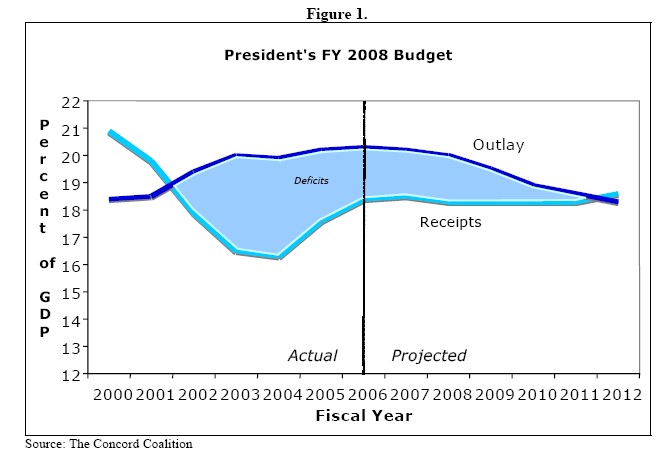

The administration proposes to spend $2.9 trillion in the fiscal year beginning October 1. To finance that spending, the budget would raise $2.7 trillion in taxes from current taxpayers and, through Treasury borrowing, $200 billion from future taxpayers. On the surface, the budget presents a benign picture. Deficits rapidly decline after 2008 and a $61 billion surplus is shown for 2012. However, that improvement in the fiscal outlook only results from projections that total spending will decline to a lower level as a percentage of the economy (gross domestic product, or GDP) than this Administration has managed to achieve in any year since it assumed office in 2001, even with one party in control of the Congress and the White House.

The baseline projections of the Administration’s Office of Management and Budget (OMB) and the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) show that if current funding levels are extended without policy changes, the budget would balance in 2011 (OMB) or 2012 (CBO). However, the rules adopted in the Budget Enforcement Act of 1990 (BEA) used to make baseline projections create distortions. For example, the projections for discretionary programs begin with amounts enacted in the current year (FY 2007) and adjust them for inflation in future years. As a result, the baseline assumes that $70 billion in funding for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan will continue on an inflation-adjusted basis. The baseline projects that spending for other discretionary programs grows by the rate of inflation (2 percent), not at the rate of economic growth (5 percent). In addition, the baseline assumes that all tax cuts expire on schedule, even if they are likely to be extended — including provisions that prevent the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which is not indexed for inflation, from ensnaring millions of additional taxpayers each year.

The budget’s outlook is far less optimistic if projections are adjusted to reflect a gradual slowdown in war funding in 2008 and beyond, discretionary spending that keeps pace with the rate of growth the economy, extension of relief from certain AMT provisions, and extension of expiring tax cuts. Under those assumptions, instead of the $170 billion surplus shown in CBO’s baseline for 2012, it is plausible that the deficit would reach $400 billion (see figure 2).

Figure 2. Source: Concord Coalition based upon CBO’s Budget and Economic Outlook: Fiscal Years 2008 to 2017.Policy assumptions can also make a big difference. In the President’s budget, three key policy assumptions produce savings or revenues on paper that will be very difficult to achieve in reality: 1. Revenue neutral reform of the AMT 2. A sudden drop in new funding for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan (from $170 billion in 2007 to zero in 2010)[3] 3. Annual increases in non-security appropriations below the rate of inflation. The cumulative effect of these assumptions improves the budget outlook by more than $800 billion over five years compared to a more plausible scenario in which AMT reform is not offset, operations in Iraq and Afghanistan are reduced by roughly two-thirds from the current level (but not eliminated) and other appropriations grow with the economy rather than inflation Table 2. President’s budget with plausible assumptionsIn billions of dollars

| 2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2008-2012 |

|

| President’s budget |

-239 |

-187 |

-94 |

-54 |

61 |

-513 |

| AMT reform |

-11 |

-70 |

-69 |

-80 |

-93 |

-323 |

| War costs |

-83 |

-112 |

-91 |

-71 |

-357 |

|

| Non-security approps. |

+8 |

-6 |

-15 |

-28 |

-37 |

-79 |

| Debt service |

-4 |

-12 |

-22 |

-33 |

-71 |

|

| Resulting deficit |

-242 |

-350 |

-302 |

-275 |

-173 |

-1,342 |

Source: Concord Coalition analysis; CBO, OMB

Aside from favorable policy assumptions, the budget is based on economic assumptions that are slightly more optimistic than those of the CBO. While the budget’s economic assumptions are clearly plausible, they are sufficiently more favorable than CBO’s as to produce $425 billion in higher revenues over the next five years, with $155 billion coming in 2012 alone. It is a demonstration in how small estimating difference can quickly add up to sizable sums. It should be noted, however, that both OMB and CBO are probably too conservative in their revenue estimates for the current year. They each project revenues of $2.54 trillion in 2007. That would be a gain of 5.5 percent over 2006. Yet, through the first four months of FY 2007 revenues have been up by 9.7 percent. In other words, this may be another year in which the deficit comes in lower than projected.

Highlights of the President’s Budget

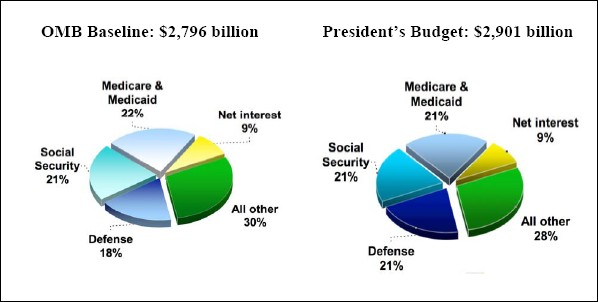

In FY 2008, The proposed budget for FY 2008 would make relatively small changes to spending compared to baseline projections (see Figure 3). Other changes would have larger effects in the out years. Specifically, the budget would:

– Increase spending for national security (defense and homeland security), including $145 billion in new funding in 2008 (and $100 billion more in FY 2007) for the operations in Iraq and Afghanistan and for other costs related to the global war on terror;

– Reduce growth in spending for Medicare and Medicaid by $101 billion relative to baseline projections over five years;

– Reauthorize the State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP) at a cost of $4.1 billion over five years;

– Terminate 91 programs and impose major funding reductions in 41 programs within the non-defense, non-security discretionary category for a savings of $12 billion;

– Extend provisions providing relief from the AMT for one year ($36 billion net), the third such one-year extension since 2004;

– Permanently extend tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003, most of which are scheduled to expire at the end of calendar year 2010 ($1.7 trillion cost);

– End the exclusion from income of employer provided health insurance and replace it with a standard deduction of $15,000 per family or $7,500 per individual for health insurance obtained through employers or privately ($121 billion cost over five years, $5 billion gain over 10 years);[4]

– Enhance reporting requirements and take other steps to narrow the estimated $290 billion “tax gap” between taxes owed and taxes collected by $29 billion over 10 years;

– Allow personal savings accounts for Social Security beginning in 2012 ($29 billion cost);

– Impose statutory caps on discretionary spending, tighten the use of “emergency” spending to evade the caps, provide for a legislative line-item veto, and establish a pay-as-you-go requirement for provisions that would increase entitlement spending.

In the immediate future the President’s budget focuses on national security, including funding for ongoing war-related costs (see Table 3). For the longer-term—2010 and beyond— the budget assumes that defense needs will rapidly abate as war-related costs decline. That, coupled with overall spending restraint, assumed revenue from the AMT, and uninterrupted economic growth, allows the Administration to show a balanced budget while attempting to lock-in the tax cuts that have defined its fiscal stance.

The Administration would increase defense outlays in 2008 by approximately 6 percent compared with estimated spending in 2007, while freezing spending for non-defense discretionary spending and slowing the growth for other programs—particularly Medicare and Medicaid. By 2012, however, the Administration projects that defense and non-defense discretionary spending will be 4 percent lower in nominal dollar terms than their estimated levels in 2007, while spending for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid will be 35 percent higher.

Figure 3: Little change proposed in the budget’s composition for FY 2008

Notes: The OMB baseline reflects concepts specified by the Budget Enforcement Act and is comparable to the Congressional Budget Office. Medicare is net of beneficiary premiums. Medicaid includes State Children’s Health Insurance Program (SCHIP).

Table 3. Composition of spending in the President’s FY 2008 budget

| Actual |

Projections |

||||

| 2006 |

2007 |

2008 |

2012 |

||

| Defense |

520.0 |

568.8 |

602.9 |

546.0 |

|

| Non-Defense |

496.7 |

511.0 |

510.8 |

492.8 |

|

| Subtotal Discretionary |

1,016.7 |

1,079.8 |

1,113.7 |

1,038.8 |

|

| Social Security |

543.9 |

581.9 |

607.7 |

789.8 |

|

| Medicare |

324.9 |

367.5 |

386.5 |

481.6 |

|

| Medicaid |

186.1 |

197.5 |

208.6 |

276.9 |

|

| Federal employee and other retirement |

102.3 |

112.1 |

117.6 |

132.0 |

|

| Unemployment |

31.0 |

31.8 |

34.1 |

41.2 |

|

| Other Income Security |

164.7 |

166.0 |

173.1 |

187.6 |

|

| Veterans |

37.4 |

38.9 |

44.8 |

53.0 |

|

| Other |

21.7 |

-30.5 |

-45.5 |

-39.7 |

|

| Subtotal: Mandatory |

1,412.1 |

1,465.3 |

1,526.8 |

1,922.5 |

|

| Net Interest |

226.6 |

239.2 |

261.3 |

284.9 |

|

| Total Outlays |

2,655.4 |

2,784.3 |

2,901.8 |

3,246.2 |

|

Source: OMB, The Budget for Fiscal Year 2008.

To its credit, the administration acknowledges the need to tackle the long-term imbalances created by the anticipated growth in Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid, but the policies proposed in the budget fall far short of what will be necessary to ensure a sustainable fiscal path.

Indeed, the 10-year entitlement savings in the budget ($359 billion) are far outweighed by the tax cut proposals, including extensions of expiring provisions ($2 trillion).

III. The budget’s priorities

The President’s budget reflects the obvious: in the near term, defense and national security funding requirements dominate. The CBO estimates that the Pentagon is spending about $8 billion a month for the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The President requests $100 billion in new funds for 2007 in addition to the $70 billion already appropriated and $145 billion for 2008 to cover the global war on terror (including war-related costs). Those amounts dwarf all but the largest non-defense programs and, unless policy makers increase revenues or incur much larger deficits, preclude spending for other priorities.

Over the longer term, the tradeoff is between taxes and entitlements, but the budget mostly avoids the choice by running higher deficits in the near term and lowering projected surpluses in the future (see Table 3). The tradeoff is also obscured by: 1) continued use of a five-year budget window, which does not display the full fiscal consequences of tax cut extensions, and 2) by assuming the extension of those tax cuts into the baseline.

Including the revenue loss from extending tax cuts in the baseline is not simply a matter of presentation. Indeed, the costs of extending the tax cuts can be found in the administration’s budget documents. The real significance is the impact this would have on the consideration of tax cut extensions in the budget process. The baseline is used as the measuring stick in applying budget enforcement rules such as the limitations on the size of tax cuts allowed by the budget resolution. If permanent extension of tax cuts were assumed in the baseline, those costs would not be subject to the tradeoffs between competing priorities that are applied to all other tax and spending proposals. In addition, including tax cuts in the baseline would effectively exempt extensions from pay-as-you-go rules.

New legislation is required to prevent the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts from expiring by 2011. Thus the decision whether to extend the tax cuts is a policy decision and should be treated as such. The revenue loss from any such legislation should be weighed against other competing initiatives that Congress and the President may wish to undertake – not simply assumed into the baseline.

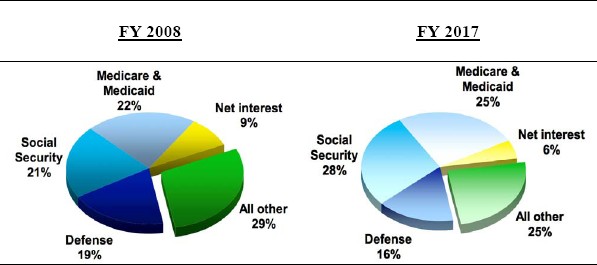

A 10-year outlook, including the impact of tax cut extensions, would provide a more realistic framework for defining the policy choices that must be confronted. Over the longer term, the growth in age-related entitlements—Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid—will take up any slack that might result from future phase-downs of defense funding. CBO estimates that spending for Social Security, Medicare, Medicaid and net interest will represent more than half of all spending in 2008. By 2017, the CBO baseline projects that three-quarters of the budget will be comprised of spending for those requirements and defense. The remaining one-fourth of the budget would cover everything else (see Figure 4).

Table 4. Estimated impact of the President’s policy proposals on the deficits (-) or surpluses (+) contained in the OMB BEA Baseline(In billions of dollars)

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

5-Years: |

| 2007 |

2008 |

2009 |

2010 |

2011 |

2012 |

2008-12 |

||||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| OMB BEA Baseline |

-185 |

-82 |

-103 |

-35 |

95 |

287 |

162 |

|||

| Proposed Changes |

||||||||||

| Taxes Cuts |

-9 |

-53 |

-34 |

-66 |

-194 |

-252 |

-599 |

|||

| Defense increases |

-37 |

-97 |

-58 |

-4 |

20 |

41 |

-98 |

|||

| Non-defense discretionary cuts |

-11 |

-13 |

2 |

11 |

24 |

30 |

54 |

|||

| Social Security personal accounts |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

-28 |

-25 |

|||

| Medicare cuts |

0 |

5 |

9 |

13 |

18 |

21 |

65 |

|||

| Medicaid cuts |

-1 |

0 |

1 |

2 |

2 |

2 |

7 |

|||

| Other changes |

0 |

6 |

8 |

0 |

1 |

-13 |

1 |

|||

| Subtotal: proposed policy changes |

-58 |

-151 |

-72 |

-45 |

-129 |

-198 |

-595 |

|||

| Net interest |

-1 |

-6 |

-12 |

-15 |

-20 |

-28 |

-81 |

|||

| Total Impact on Baseline |

-59 |

-157 |

-84 |

-59 |

-149 |

-226 |

-676 |

|||

| President’s Budget |

-244 |

-239 |

-187 |

-94 |

-54 |

61 |

-514 |

|||

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The growth in spending for Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid raises fundamental questions of generational equity. Older people benefit. Younger people pay taxes. The number of people age 65 and older will double by 2050, while the size of the working-age population will only increase by 16 percent. That will confront those younger generations with larger burdens than future retirees faced when they were working and paying taxes. Although economic growth will help make costs more affordable, that growth alone will not be sufficient to address the growing costs of current-law benefits. Hard policy choices are inevitable. The only question is whether we’ll make them now or let the whole burden of both current and projected deficits fall on the future.

(CBO baseline projections January 2007)

The Administration proposes to slow the growth in spending for Medicare and Medicaid –which are growing faster than the economy and are the major cause of the budget’s long-term problems. The Medicare proposals would reduce the growth in payments to health care providers and reduce federal subsidies to high-income beneficiaries. Over the next 75 years, OMB estimates that those changes will reduce Medicare’s unfunded liability (costs in excess of payroll tax and premium income) by 25 percent—the equivalent of expected cost of the new prescription drug program (Part D) to general taxpayers. But that would still leave substantial unfunded costs. The Medicaid proposals would result in lower payments to the states, which administer the program. Despite the pressing need to rein in the cost of health care entitlements, the proposals to do so—whether from the Administration or other sources—are likely to meet heavy resistance from health care providers and beneficiaries who are hoping to find someone else to foot the bills.

As for tax policy, the President again proposes to make permanent tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003. Most of these provisions do not expire until December 2010, but the Administration proposes to lock them in now. That would reduce revenues in FY 2008-2017 by $1.6 trillion according to the administration[5] Nearly 80 percent of that revenue loss would occur in the second five years — beyond the administration’s budget window.

One tax cut that has expired is the provision that provided temporary relief from the AMT for middle-income and upper-middle income families. The budget avoids proposing a permanent fix for that provision and instead proposes one year of relief.

Implicitly, the budget contains a rather sizable tax increase because it assumes a growing revenue windfall from the AMT. Administration spokesmen have indicated that the budget only contains a one-year “patch” for AMT relief because they want to work with Congress on a revenue neutral overhaul (or elimination) of the AMT. It is a fiscally responsible suggestion because it implicitly accepts the concept of applying pay-as-you-go budgeting to taxes as well as spending — something the President has opposed in the past. As yet, however, neither the administration, nor the Democrats in Congress have put forward a credible plan for raising other revenues or cutting spending enough to fully offset AMT reform.

Without revenue increases, the President’s budget turns to spending restraint to close budget gaps. But in the budget, spending restraint is largely limited to discretionary spending (falling defense spending and a virtual freeze on non-defense programs). Over the five-year period 2008 to 2012, the Administration’s budget shows that entitlements will grow faster than the economy due to Medicare and Medicaid. On the non-defense discretionary side of the budget the Administration proposes terminations and major reductions to 141 programs for eventual savings of $12 billion over FY 2007. The Administration has tried without success to reduce or eliminate the same programs in past budgets. Nevertheless, the budget projects non-defense spending will decline to 2.8 percent of GDP, a full percentage point below its average level since 2001.

IV. What comes next?

All presidential budgets are advisory, and all the more so when presented to a Congress of the opposite party. In the end, Congress must decide on spending and tax levels, with the President left to accept them or veto them.

In the coming weeks, the new Democratic leaders of the House and Senate Budget Committees, John Spratt (D-SC) and Kent Conrad (D-ND), will attempt to put together their respective budgets in a way that can pass each chamber and eventually be combined into a Joint Budget Resolution. They need not be guided by the President’s budget, although with small majorities ¾ particularly in the Senate ¾ straying too far from the President’s numbers clearly risks a veto strategy on any legislation to implement the Budget Resolution policies.[6]

Alternatives to the President’s budget policies face the same hard fiscal realities. The much discussed proposal to repeal the tax cuts for upper-income taxpayers would provide only temporary and relatively modest new resources when compared to the CBO baseline. The revenue impact of rolling back the rate cuts in the top two tax brackets to their pre-2002 levels would produce about $30 billion a year through 2010 according to the Tax Policy Center. Repeal of reductions in capital gains and dividend tax rates would provide another $30-35 billion per year through 2010. Those amounts are not trivial, but they would not provide a permanent source of financing for all the potential uses (e.g., providing subsidies to reduce the number of people without health insurance, expansion of existing programs and benefits).

The Democrats may choose to treat the President’s budget as “dead on arrival,” but that still leaves them with the task of assembling their own budget. Now that they share responsibility for the nation’s fiscal future, opposition to the President’s budget is not enough. As the process unfolds, both sides may find it desirable, as well as responsible, to look for targets of opportunity

AMT reform

Democrats, and indeed The Concord Coalition, have been critical of the administration for leaving the cost of AMT reform out of the budget. The argument has been that assuming no AMT reform is unrealistic because neither the administration nor the Congress supports allowing the AMT to continue on its current law path. The problem is that foregoing the revenue assumed from the AMT, without expanding the deficit considerably, would require other tax increases or spending cuts of about $1 trillion over the next 10 years.

Because AMT reform will be a challenge for Democrats as well when they craft their budget resolution in the coming weeks, the question of how to provide revenue neutral AMT relief offers a target of opportunity for bipartisan negotiations. If the administration is serious about finding a revenue neutral fix for the AMT, and if Democrats are willing to engage on long-term spending control of entitlement programs, the proper condition will exist for a meaningful discussion. If not, leaving AMT reform out of the budget is still nothing but a scoring gimmick – for both sides.

Medicare market basket and other health care related measures

Medicare payments to healthcare providers are adjusted annually for medical price inflation. The budget proposes to reduce that adjustment factor by 0.65 percent below the level implied by that market basket price index in order to encourage more efficient delivery of services. Opponents to the proposal argue that the lower indexing will adversely affect the quality of health care for Medicare beneficiaries and may ultimately reduce their access to care if providers refuse Medicare patients. The hard truth is that there are only direct two ways to reduce the growth in Medicare costs: pay health care providers less or reduce the amount of health care that patients consume. Although both parties agree that the goal is to deliver better quality of care while controlling costs, it is much easier said than done. As it stands, this budget proposal merely repeats judgments made in the past—it is easier to squeeze health care providers than Medicare beneficiaries. It could, however, be the basis for a more comprehensive way in which the efficiency of health care delivery can be improved.

Another opportunity for bipartisan negotiation is the President’s proposal to end the exclusion of employer provided health insurance from individual income. This "tax expenditure" costs about $200 billion in forgone revenue and encourages very expensive policies that leave employees with few, if any, out-of-pocket costs and little cost consciousness. The President’s proposal would end the exclusion and replace it with a tax credit ($7,500 per single individual and $15,000 for family) to cover the cost of health insurance. and The budget would use the initial savings for new health insurance deductions and exclusionsto provide subsidies to help uninsured lower-income individuals and families obtain insurance. Whether or not Democrats agree with the specifics, this proposal is worthy of consideration because it puts a major tax break on the table, and implicitly accepts the pay-as-you-go concept for tax initiatives and places a limit on so called “Cadillac” health insurance coverage that many believe encourages over consumption of health care services.

A final promising area for bipartisan negotiations in this regard is the proposal to introduce income-related premiums to Medicare’s prescription drug program. This concept is an equitable way to reduce the rising burden of entitlement spending — not just for Medicare, but for all major federal benefit programs. It extends the principle already introduce in Medicare Part B that beneficiaries who can afford to pay more for their coverage should do so. The proposal recognizes that Medicare is a highly subsidized program. Premiums cover only 25 percent of program costs. General revenues—which largely come from the working-age population—cover cover the rest. Given the large general revenue subsidy and the need for long-term savings from what most concede is an unsustainable path, Medicare beneficiaries should be expected to bear some of the costs, particularly if they can afford to. beneficiaries who can afford to pay more of their fair share should do so.

The income-relating proposal should be viewed in the long-term context and not as a proposal whose need is driven by the quest for a short-term balanced budget. The prescription drug benefit was unaffordable when enacted. This proposal, if fully implemented, would only shave about $2 trillion from a long-term unfunded obligation of $32 trillion for Medicare as a whole.

Ultimately, Medicare and Medicaid cost growth must be addressed through fundamental health care reform, and not just through cost shifting. That is no reason, however, to avoid incremental steps that make sense on their own and that can achieve substantial savings. As is often observed with policy proposals, perfection should not be the enemy of the good.

Tax gap

Members of both parties have expressed a growing desire to increase revenues by closing the so-called “tax gap,” the difference between taxes that are owed and the revenues that are actually collected. The Internal Revenue Service estimates that the tax gap is about $290 billion. As policymakers formulate plans to collect that money, however, they would do well to listen to the caveat of Treasury Secretary Henry Paulson who told the Senate Finance Committee, “On this particular issue, I think we both of us owe it to the American people to take some of the mystery out of this, because I don’t think it does anybody a service to let the American people think there’s a big pot of gold there and that we can tap into that gold to fund all sorts of things without there being a big cost to that.”

V. Conclusion

The President’s FY 2008 budget represents a continuation of priorities established at the beginning of the Administration—tax cuts and national security. The improvement in the budget’s bottom line is largely attributable to economic recovery and the growth in revenues, not to spending restraint.

Missing from the President’s budget is a complete perspective on the long-term fiscal outlook. The budget does not provide estimates for 2013-2017, as CBO does for its baseline, thereby hiding the impact of major policy changes. The extension of tax cuts and the proposal to establish voluntary personal savings accounts will have significant budgetary impact at the same time that more and more baby boomers become eligible for Social Security and Medicare benefits. But the Administration chooses to avoid a fuller accounting of its policy proposals.

The conventional wisdom holds that policymakers and the public cannot focus on long-term budget challenges because there are much more immediate concerns that require attention. While that may be true, there is no excuse for making those problems worse. Whether new tax cuts or entitlement expansions, at the very minimum policymakers should have to identify the longer-term consequences or benefits of their policy proposals. Anything less denies the public the opportunity to make informed choices.

[1] The President’s goal of restoring balance by 2012 is one that Concord supports. It should be noted, however, that this goal includes the "off-budget" Social Security surplus. The "on-budget" total in 2012, under the President’s budget, is a deficit of $187 billion. The total five-year on-budget deficit is $1.7 trillion. At the beginning of the Bush Administration a bipartisan consensus existed to keep Social Security “off-budget” in fact as well as in name. The Concord Coalition supports further efforts to restore a balanced budget excluding the Social Security surplus.

[2] The Administration will send budget documents to the Congress in February 2008 and January 2009, but because of the upcoming presidential election, those proposals are unlikely to garner serious attention.

[3] For the first time, the administration has presented estimated war costs for the budget year ($145 billion in 2008). This was done in response to bipartisan complaints about prior budgets that omitted future war costs. It is an improvement from past practice, but the placeholder amount for 2009 is just $50 billion and no new funds are included beyond 2009. Thus, the budget still understates likely future war costs.

[4] A preliminary estimate of this proposal by the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) reaches a dramatically different conclusion. According to JCT, this proposal would raise revenues by $40 billion over five years and $526 billion over 10 years.

[5] Preliminary estimates by the Joint Committee on Taxation put the 10-year revenue loss at $1.9 trillion. This does not include the outlay effect of certain expiring provisions.

[6] The Budget Resolution itself is not legislation and is not subject to a presidential veto. However, unless the Congress waives its own rules, appropriations bills or tax and entitlement legislation must conform to designed to achieve the goals of the Budget Resolution and, once passed by the Congress, are subject to a veto.