Like the legislative equivalent of Groundhog Day, Washington lawmakers are once again in a last-minute rush to pass an end-of year omnibus spending bill that funds the federal government for a fiscal year already underway (FY 2023) – plus a host of smaller measures Congress failed to get across the finish line during the other 364 days of the year. This end-of-year sprint has become an annual rite of passage (pun intended) and reflects a budget process that is badly broken.

Back in the days of “regular order”, both chambers would adopt identical budget blueprints in April and begin drafting appropriations bills. Spending bills would come to the floor, one at a time, during the summer months where they would be debated, possibly amended, and sent to the opposite chamber for their approval. Conference committees would meet in August and September to hammer out any differences, and final versions of appropriations bills would be approved by both the House and Senate and sent to the President for enactment before the start of the new fiscal year on October 1st .

The last time Congress completed this job on time was 1996.

Congress now routinely relies on “omnibus” spending bills to fund the government. These bills are massive (in page numbers and dollars), are drafted in secret by a few select lawmakers, and often contain extraneous matter. They are released for review at most only a few days (and sometimes only a few hours) before members are asked to cast their vote—and against the backdrop of a certain government shutdown during the holidays if the measure fails to pass. Sadly, this year’s omnibus funding bill, HR 2617, follows this fiscally irresponsible holiday pattern.

Big Increase in Base-Level Government Funding

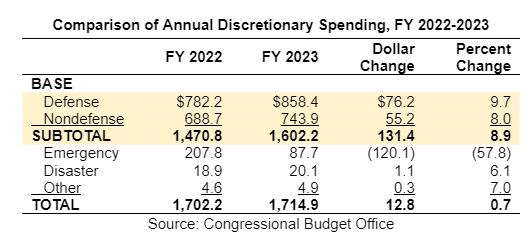

The omnibus provides a grand total of $1.7 trillion in discretionary appropriations for FY 2023. This is a mere 0.7% increase over FY 2022 spending, but that’s solely the result of the COVID “dividend”—the end of last year’s emergency healthcare spending for the COVID pandemic. Look beneath the surface and there are some startling details. Regular (base or non-emergency) appropriations for defense and nondefense categories are practically stratospheric—an increase of 9.7 percent and 8.0 percent, respectively. Overall, base discretionary spending will rise nearly 9 percent in FY 2023. Adding to our concern: this new base level of discretionary spending will be built into next year’s budget baseline and will add hundreds of billions to the projected deficits and debt in future years.

Moreover, at a time of 7 percent annual inflation, fiscal and monetary policy should be working in tandem to rein in inflation. But the significant fiscal stimulus provided by the discretionary spending bills in the omnibus will make the Federal Reserve’s job tougher, not easier.

Congress Showed Some Restraint with Extraneous Matters

Since an omnibus is typically the last piece of legislation considered during a session of Congress, there is enormous pressure to attach other items, some of which can add enormous cost. Earlier this year, The Concord Coalition and other fiscal responsibility groups were very concerned that the omnibus would extend a broad swath of expired or expiring tax credits without any offsets, which would have added billions (trillions?) more to our national debt. Luckily, Congress showed some restraint (or merely failed to generate consensus) and the budget busting tax title did not materialize.

Still, the omnibus does contain some unrelated riders:

- Legislation to overhaul the Electoral Count Act to clarify that the vice president’s role in counting electoral votes is clerical only, and to raise the threshold for the number of senators and representatives needed to object to state-certified electoral ballots.

- A recent Senate-passed bill to ban the use of the social media app TikTok on government devices.

- Bipartisan retirement savings legislation negotiated by the House Ways and Means and Senate Finance committees.

- Extensions of various expiring Medicare and other health care-related provisions affecting Medicaid, the Children’s Health Insurance Program, and more.

Treatment of Statutory PAYGO Sequester is a Missed Opportunity

Another major disappointment in the omnibus is how it treats a pending sequester triggered by overspending. According to the Statutory Pay-As-You-Go-Act of 2010 (S-PAYGO), the $1.8 trillion American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) added a $370 billion debit to the S-PAYGO scorecard each year for FYs 2022-2026. Because the sequester was so large, however, lawmakers added language to last year’s omnibus to roll the balance into FY 2023 creating a $742 billion debit in 2023—a sequester so large as to be un-implementable (it exceeds the size of the sequesterable base). Congress then repeated this “punt” in the current omnibus–pushing the $742 billion S-PAYGO balance into 2025.

The choice to roll the current S-PAYGO balance two years ahead (instead of one) is conspicuous because 2025 is also the year several individual and small business-related tax cuts enacted by the Trump tax reform bill in 2017 (the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act), are scheduled to expire. Extending those cuts will cost trillions and will further add to the debit on the S-PAYGO scorecard(s) in 2025, fueling bipartisan agreement to simply wipe the scorecard(s) clean and forget a sequester was ever in order. This would, in effect, gut once again any budget enforcement efforts to keep spending increases and tax cuts from increasing our national debt.

But S-PAYGO exists for a reason. It was part of the agreement to raise the debt limit in 2010 and its purpose is to end the practice of debt-financed tax cuts and spending increases. As our national debt reaches historic proportions and rising interest rates cause net interest costs to displace other budget priorities, it’s time to give S-PAYGO some teeth. The current sequester is too large to implement in toto—yes—but instead of punting it further into the future (where it will certainly be eliminated by subsequent legislation), a more responsible approach would have been to use the omnibus to implement the sequester over a longer timeline (e.g., 10-20 years).

Stop the Madness

With each passing omnibus, Congress misses an opportunity (and time) to make reasonable changes that will help put the federal government’s finances on a more sustainable path—and more often an omnibus makes the problem worse. These gargantuan bills, rammed through at the last minute under threat of a shutdown, deprive most lawmakers, the media and the public adequate opportunity to scrutinize the individual provisions and understand what’s in them. By adopting a realistic budget blueprint on time each year, using the regular appropriations process to reduce the rate of growth in discretionary spending (not cut, just reduce the rate of growth), and using the reconciliation process to make meaningful, bipartisan down payments on tax and entitlement reforms, Congress and the President can avoid the trainwreck we know lies ahead.

It’s time to stop the madness.