Download the pdf: The Social Security Un-Fairness Act

Introduction

In a rare display of bipartisanship, more than 300 members of the U.S. House of Representatives have co-sponsored legislation (H.R. 82, “Social Security Fairness Act”) to increase benefits for individuals who receive both Social Security and a pension based on employment that was not covered under Social Security.[1] Unfortunately, rather than addressing the obvious flaws in current law, this legislation would provide these individuals with more generous benefits than everyone else who receives Social Security. It would also cost $183 billion over the next 10 years and advance trust fund insolvency by six months.[2]

Bipartisan support for this legislation reflects the understandable desire to appease a key political constituency, namely state and local government employees; but it also reflects the unfortunate failure to recognize the legitimate reasons for reducing their benefits. Rather than capitulate to political pressure, decrease benefit fairness, and accelerate trust fund insolvency, Congress should consider a better way to coordinate Social Security benefits with non-covered pensions while still maintaining fiscal discipline.

This issue brief explains how two current provisions of law, the Government Pension Offset (GPO) and the Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) serve a vital, albeit flawed, role in attempting to achieve parity between covered and non-covered workers. Alternatives to these provisions will be examined in a subsequent issue brief.

Non-Covered Employment

When Social Security was enacted in 1935, state and local government employees were excluded from coverage. Voluntary coverage was offered in the early-1950s, and coverage became mandatory in 1990, except for employees participating in a pension plan that provides comparable retirement benefits. According to the latest available data, more than 28 percent of state and local government employees are exempt from Social Security, ranging from a low of 3 percent in Vermont to a high of 97 percent in Massachusetts and Ohio.[3]

Despite being exempt from Social Security, most non-covered employees become eligible for benefits, either as the spouse of a covered worker or from working in covered employment before, during, or after their own non-covered employment. However, instead of collecting both Social Security and their pension from non-covered employment, they are subject to two provisions of current law (discussed below) that can reduce or eliminate their Social Security benefits. While that may seem unfair and justify their repeal, these provisions are intended to maintain benefit parity between covered and non-covered workers.

Statutory Provisions Aimed at Improving Parity

Social Security differs from employer-provided pensions in several respects. Pension plans typically provide a proportional benefit equal to 2 or 3 percent of a worker’s highest 3 to 5 years of earnings, multiplied by the number of years of service.[4] There are no spousal benefits, and survivor benefits reduce retirement benefits. Social Security provides a progressive benefit, with lower-wage earners receiving a proportionally larger benefit than higher-wage earners, based on the highest 35 years of earnings.[5] It also provides auxiliary benefits to spouses and survivors without reducing retirement benefits. Because of these differences, combining Social Security with a non-covered pension plan can create disparities and result in unintended consequences.

Dual Entitlement Rules

In the case of married couples, Social Security provides auxiliary benefits to spouses and survivors which are based on the retirement benefit of each spouse.[6] Spouses and survivors can receive as much as 50 percent and 100 percent, respectively, of the retirement benefit.[7] These auxiliary benefits are reduced $1-for-$1 by the amount of retirement benefits. This means each spouse effectively receives the greater of: (1) their own retirement benefit, or (2) an auxiliary benefit based on their spouse’s retirement benefit. The offset between auxiliary benefits and retirement benefits is known as the dual entitlement rule.[8]

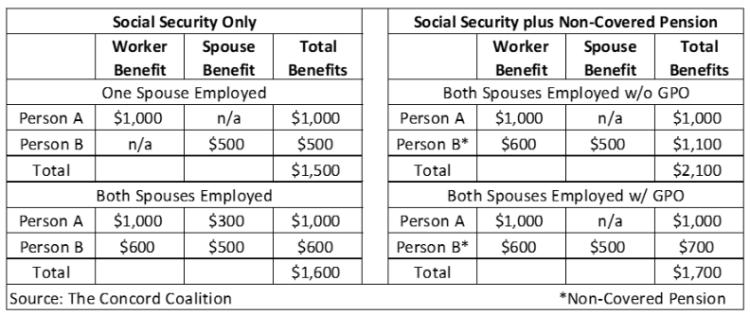

Before the Government Pension Offset (GPO) was enacted in 1977, non-covered workers could collect their own pension plus an auxiliary benefit without any reduction. As Figure 1 shows, without the GPO, couples with covered and non-covered employment could receive more than couples with only covered employment. In some cases, non-covered workers still receive more because the GPO offset is $0.67 per $1, while the Social Security offset is $1-for-$1.[9]

Figure 1: Social Security Benefits and Non-Covered Pension for Hypothetical Workers

Progressive Replacement Rates

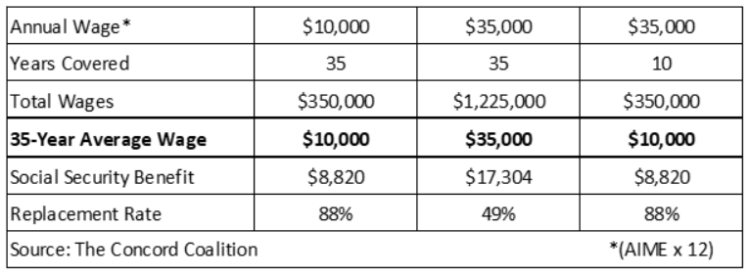

Social Security provides higher replacement rates for lower-wage workers, and lower replacement rates for higher-wage workers. Replacement rates measure the ratio of benefits to wages – or how much of a worker’s earnings are replaced by Social Security benefits in retirement. For example, those who earn $10,000 a year for 35 years would get a benefit equal to 88 percent of their 35-year average wage, while those who earn $35,000 a year for 35 years would get a benefit equal to 49 percent of their 35-year average wage, assuming retirement at age 65. (Figure 2)

Workers only need 10 years of wages to qualify for retirement benefits, but their benefits are based on the average of their highest 35 years of wages. Any year they did not work in a job covered by Social Security becomes a $0 when calculating their 35-year average wage. The progressive benefit formula applies regardless of whether average wages are low due to years with no earnings (i.e., unemployment), or due to years with non-covered earnings (i.e., non-covered employment). As a result, a covered worker who earns $10,000 a year for 35 years, and a covered worker who earns $35,000 a year for 10 years will have the same replacement rate. (Figure 2)

Figure 2: Social Security Benefits for Hypothetical Workers at Age 65 in 2022

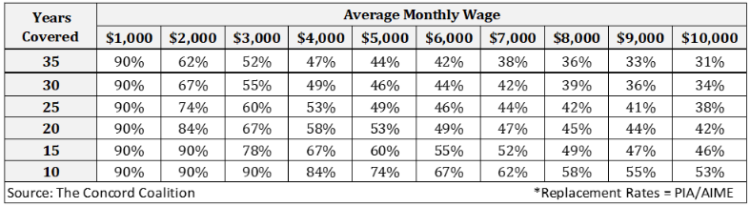

The Windfall Elimination Provision (WEP) was enacted in 1983 to prevent workers who were exempt from Social Security because they were covered by another pension plan from receiving the higher replacement rates that were intended for lower-wage workers. Figure 3 shows how replacement rates at the full retirement age (FRA) vary by the level of wages and the number of years of covered employment.[10] For workers with 35 years of coverage, replacement rates range from 90 percent at $1,000 to 31 percent at $10,000. As the number of years of coverage declines from 35 to 10, replacement rates rise at every wage level.

Figure 3: Replacement Rates at FRA by Average Monthly Wage and Years of Coverage

The purpose of the WEP is to reduce the replacement rate of workers who did not contribute to Social Security throughout their entire career due to their years of non-covered employment. In theory, this reduction should correspond to the level of wages. For example, workers earning $5,000 per month should have a 44 percent replacement rate regardless of whether they worked 10 years or 35 years.

Reform Rather than Repeal

Opposition to the GPO and WEP among state and local government employees is understandable. No one wants to receive fewer benefits. However, the failure to recognize the legitimate reasons for reducing their benefits is no justification for repeal. A better approach is to reform these provisions.

There are obvious flaws in the application and enforcement of the GPO and WEP provisions that result in substantial non-compliance and overpayments. First, the Social Security Administration (SSA) must primarily rely on individual self-reporting.[11] Individuals who fail to report their non-covered pension are able to avoid the reductions. The SSA has proposed to fund a data exchange with state and local governments to provide non-covered pension information. This data sharing would result in ten-year savings of nearly $11 billion to the Social Security trust funds.[12] Alternatively, the SSA could use its data on non-covered employment to request 1099-R pension data from the IRS to identify individuals with non-covered pensions.[13] But neither proposal has been funded or approved.

Second, the SSA’s “administrative finality” policy generally prohibits the correction of erroneous benefit decisions after four years, absent fraud or similar fault, or unless the correction would be favorable to the beneficiary.[14] That means if the SSA fails to promptly identify individuals who should have been subject to the GPO or WEP provisions, they cannot correct the mistake. The SSA’s Office of the Inspector General (OIG) has identified thousands of erroneous benefit decisions resulting in millions of dollars of improper payments and continues to urge the agency to change this policy.[15]

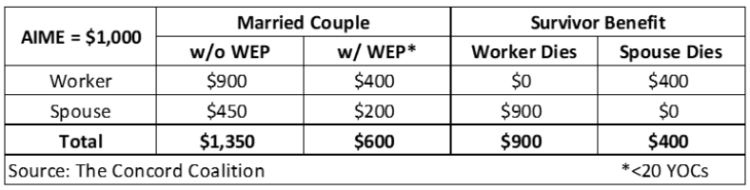

Third, when retirement benefits are reduced by the WEP, spousal benefits are also reduced. However, the WEP does not apply to survivor’s benefits, which results in the inequitable treatment of workers relative to their spouses. As shown in Figure 4, if the worker dies, the surviving spouse receives an unreduced benefit ($900), whereas, if the spouse dies, the surviving worker continues to receive a reduced benefit ($400).

Figure 4: Social Security Benefit for Hypothetical Workers, Spouses, and Survivors

If the SSA were able to obtain non-covered pension information, revise its administrative finality policy, and apply the WEP to spousal benefits, it could more fairly and accurately implement the GPO and WEP provisions, while generating billions of dollars in savings that could be used to offset the cost of reforming these provisions.

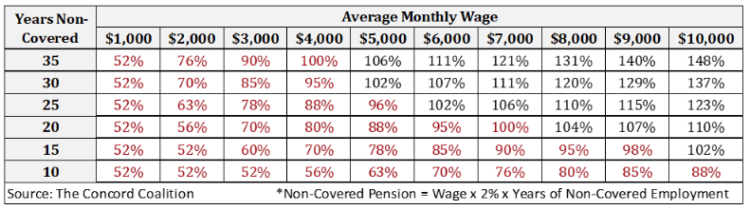

The GPO and WEP were enacted to address the legitimate need to prevent workers with non-covered pensions from receiving more generous benefits than everyone else who receives Social Security. Unfortunately, neither provision consistently achieves that goal. For example, the GPO reduces spousal and survivor benefits by two-thirds of the non-covered pension, whereas the dual entitlement rule reduces spousal and survivor benefits by 100 percent of the Social Security retirement benefit. Figure 5 shows the GPO reduction almost never equals the dual entitlement reduction.[16] The numbers in red (<100%) indicate the GPO reduction is less than the dual entitlement reduction, and the numbers in black (>100%) indicate the GPO reduction is greater than the dual entitlement reduction.

Figure 5: GPO Reduction as Percentage of Dual Entitlement Reduction

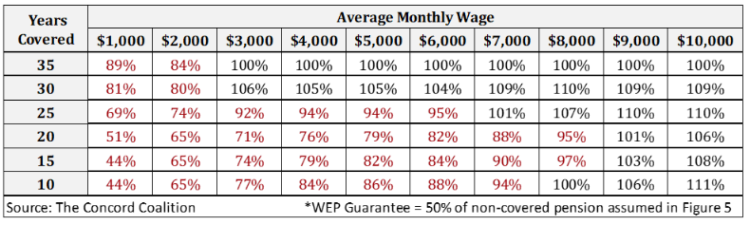

Unlike the GPO which provides more favorable treatment to lower-wage workers, the WEP provides more favorable treatment to higher-wage workers. Figure 6 shows replacement rates under the WEP as a percentage of replacement rates for workers with 35-years of covered employment (see Figure 3). The numbers in red (<100%) indicate the WEP replacement rate is less than the 35-year replacement rate, and numbers in black (>100%) indicate the WEP replacement rate is greater than the 35-year replacement rate.[17]

Figure 6: Replacement Rates under WEP as a Percentage of 35-Year Replacement Rates

Because of the obvious flaws in the application, enforcement, and policy outcomes of the GPO and WEP provisions, several alternatives have been proposed to better coordinate Social Security benefits with non-covered pensions. These alternatives generally rely on non-covered earnings data, an option that was not available when the GPO and WEP were enacted due to limitations in the SSA’s data collection. These alternatives will be examined in a subsequent issue brief.

Conclusion

The GPO and WEP were enacted to reduce the Social Security benefits of workers with non-covered pensions to maintain parity with workers who are only covered by Social Security. Unfortunately, these provisions rely on self-reporting, making them difficult to enforce, thereby resulting in substantial non-compliance and overpayments. Moreover, they do not accurately duplicate the dual entitlement rules or provide consistently progressive replacement rates. However, these flaws do not justify their repeal. There is a legitimate need to maintain parity between covered and non-covered workers. Fortunately, there are several ways to reform these provisions while still maintaining fiscal discipline. Congress should reform rather than repeal these provisions.

[1] H.R.82 – 117th Congress (2021-2022): Social Security Fairness Act of 2021 | Congress.gov

[2] H.R. 82 (cbo.gov); DavisSpanberger_20220720.pdf (ssa.gov)

[5] Social Security Replacement Rates: “Nudging” in the Wrong Direction? | Concord Coalition; See Appendix

[6] Couples must be married at least one year to be eligible for spouse and survivor benefits, or at least 10 years in the case of divorce. Widows and ex-spouses who remarry after they attain age 60 can also collect auxiliary benefits based on their former spouse’s benefit amount, or their current spouse’s benefit amount, whichever is higher.

[7] These results assume both spouses have attained the full retirement age. Benefits paid at earlier ages are subject to actuarial reductions. Benefit Reduction for Early Retirement (ssa.gov); The Widow(er)’s Limit Provision (ssa.gov)

[8] SSA – POMS: RS 00615.020 – Dual Entitlement Overview

[10] Normal retirement age (NRA) (ssa.gov)

[11] GPO and WEP apply to federal employees hired before 1984. The Office of Personnel Management (OPM) provides the SSA with information on individuals who are receiving non-covered pensions.

[12] BUDGET-2021-PER.pdf (govinfo.gov), Table 6-1; CBO Estimate of the President’s Fiscal Year 2021 Budget; CBO’s estimate is $3.4 billion over ten years.

[13] Although the SSA has access to other tax return information, the IRS has denied access to 1099-R data.

[14] The Social Security Administration’s Administrative Finality Policy (ssa.gov)

[15] Follow-up on Old-Age, Survivors and Disability Insurance Benefits Affected by State and Local Pensions (ssa.gov); Follow-up: Dually Entitled Beneficiaries Who Are Subject to the Windfall Elimination Provision and Government Pension Offset (ssa.gov)

[16] The comparison assumes the non-covered pension and the Social Security benefit are based on the same level of average wages for both covered and non-covered employment.

[17] The WEP guarantee limits the Social Security benefit reduction to no more than 50% of the worker’s non-covered pension.

Continue Reading