Downloadable pdf: Social Security’s Debt Limit Escape Clause

Introduction

Last month, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen notified Congress that the federal government had reached the current debt limit ($31.4 trillion).[1] As a result, the Treasury Department has undertaken traditional “extraordinary measures” that are expected to allow the government to continue borrowing through at least early June. Unless Congress increases or suspends the debt limit before the extraordinary measures are exhausted, the government would no longer be able to pay all its bills on time, resulting in a default on at least some of its legal obligations.

Some observers suggest the failure to increase the debt limit could also prevent the payment of Social Security benefits.[2] However, this conclusion overlooks a provision of current law – an escape clause – that permits the disinvestment of the Social Security trust funds whenever necessary to pay benefits.[3]

This issue brief explains how the debt limit affects the government’s ability to pay its bills, examines how current law allows the payment of Social Security benefits even when there is a delay in raising the debt limit, and considers how utilizing this provision could inadvertently result in temporarily funding other government programs after traditional extraordinary measures have been exhausted.

Debt Limit and Extraordinary Measures

The Constitution (Article I, Section 8) grants Congress the power to “borrow money on the credit of the United States.” Congress delegated this power to the Treasury Department, subject to various restrictions, which gradually evolved into an aggregate debt limit.[4] The limit has been increased over the years, the last time in December 2021 to the current level of $31.381 trillion.[5] Last month, the government reached this limit, and the Treasury began implementing extraordinary measures that are expected to allow the government to continue borrowing until at least early June.

To understand how the government can continue borrowing despite reaching the debt limit, it’s necessary to distinguish between two categories of debt: (1) debt held by the public, including the Federal Reserve; and (2) debt held by government trust funds, including Social Security and Medicare.[6] Both categories are included in the debt subject to limit, but they are fundamentally different.[7]

Publicly held debt is the cumulative amount borrowed from foreign and domestic investors to fund the government when there is a shortfall between taxes and spending. Debt held by trust funds is the result of intergovernmental transfers between government accounts that have no direct or immediate effect on global financial markets (but will in the future when trust fund debt is exchanged for public debt). As the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) has explained:[8]

“Issuing debt securities to Government accounts performs an essential function in accounting for the operation of these [trust] funds…. These [securities] generally provide the [trust] fund with authority to draw upon the U.S. Treasury in later years to make future payments on its behalf to the public…. However, issuing debt to Government accounts does not have any of the current credit market effects of borrowing from the public. It is an internal transaction of the Government, made between two accounts that are both within the Government itself.”

Because public debt and trust fund debt are both included in the debt limit, when the combined amount reaches the limit, the Treasury Department can temporarily redeem (or disinvest) debt held by certain government accounts such as the Civil Service Retirement System (CSRS) and the Thrift Savings Plan (TSP).[9] By reducing the amount of debt held by these trust funds, the government can borrow an equal amount from the public without exceeding the limit. This exchange of trust fund debt for public debt is one of several accounting transactions – collectively referred to as “extraordinary measures” – available to postpone default.[10]

Eventually, however, these measures will become insufficient to allow the government to continue borrowing from the public. At that point, the government would be unable to pay all its bills on time, thereby forcing it to default on at least some of its legal obligations to contractors, employees, beneficiaries and perhaps even investors. Under the most likely scenario, the government would delay payments until sufficient funds were available. If sufficient funds were not available to pay all of the bills received each day, they would all be held until the following day, or longer if necessary.[11] This delay would constitute a default – the failure to make payments when due – resulting in interest penalties on certain payments and risking the stability of global financial markets. It’s unclear how severe the market reaction would be to such a delay, but interest rates on government debt could increase substantially.

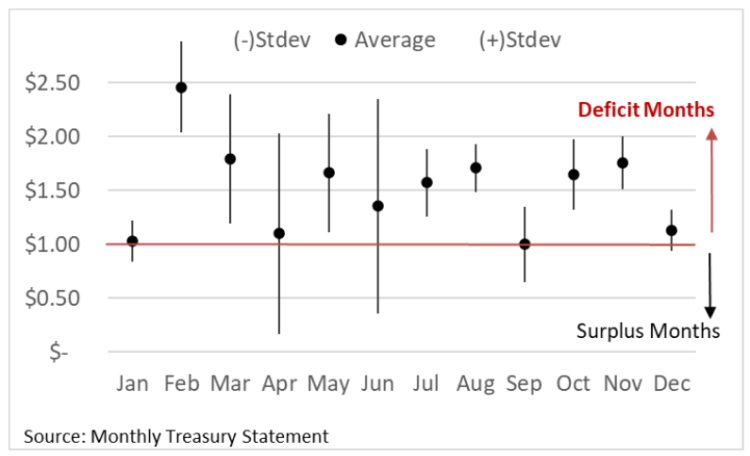

The length of the delay would depend on when the extraordinary measures were exhausted. The government’s cash-flow varies considerably within each month and across months throughout the year. Figure 1 shows the ratio of the federal government’s average monthly receipts and outlays (plus or minus one standard deviation) between Fiscal Years 2010 and 2022.[12] When spending exceeds revenue, the ratio is greater than $1.00 indicating a deficit. When revenue exceeds spending, the ratio is less than $1.00 indicating a surplus.

Receipts tend to exceed outlays in five months (January, April, June, September, December) and outlays tend to exceed receipts in the other seven months. In some months, the shortfall is particularly large. For example, in February, the government spends on average nearly $2.50 for every $1 of receipts.[13] Thus, the delays would be considerably longer if the extraordinary measures were exhausted during a month of substantial deficits.

Figure 1: Average Monthly Spending Per Dollar of Average Monthly Receipts

Given the variation between receipts and outlays, it would be difficult for the government to predictably prioritize payments – i.e., pay some bills while not paying others. Prioritization would require the government to delay all payments until the end of each day. Once it knew how much was collected in daily receipts, the government could pay the bills it could afford based on some predetermined list of priorities, which may or may not exist and may or may not be technically or administratively feasible, except perhaps principal and interest on the debt.[14] Assuming the government could pay all the priority bills on a given day, it would then have to choose between paying some or all of the remaining bills to the extent it could or keep some or all of the remaining receipts in case they were needed to pay priority bills the next day. Meanwhile, in this scenario non-prioritized payments would remain waiting in the queue and recipients would experience continued delays.

The government’s cash-flow is simply too variable and uncertain from day-to-day to adopt any rational payment policy other than delay payments until sufficient funds become available. As a result, some observers have concluded that monthly Social Security benefits are also at risk of being delayed. But this conclusion overlooks a provision of current law that permits the disinvestment of the Social Security trust funds when necessary to pay benefits.[15]

The Social Security Escape Clause

When Congress delayed a debt limit increase in the mid-1980s, the Treasury Department suspended the investment of payroll taxes and redeemed a portion of the debt held by the Social Security trust funds to allow the continued payment of benefits.[16] These actions, like those now permitted for CSRS and TSP, allowed the Treasury to reduce the amount of debt held by government accounts to make room under the debt limit to borrow additional money from the public without exceeding the limit. As observed in an SSA Actuarial Note:[17]

“This practice also enabled the Federal government to continue other, non-Social Security financial transactions for a longer period than otherwise could have occurred. As a result, the Treasury action was viewed by some as an inappropriate use of Social Security funds and was the source of considerable controversy.”

When Congress again delayed a debt limit increase in the mid-1990s, it provided the Treasury with temporary authority to issue public debt that would not count against the debt limit.[18] The amount authorized was equal to the Social Security benefits expected to be paid the following month. At that time, benefits were typically paid by direct deposit on the third day of each month.

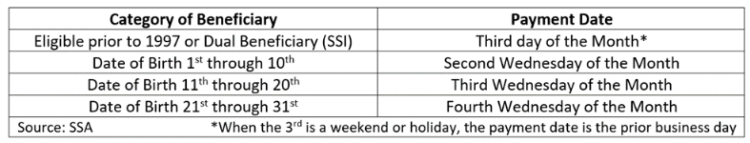

In 1996, Congress enacted a law to prohibit the disinvestment of the Social Security trust funds for any purpose other than the payment of benefits.[19] This law provided an escape clause allowing the payment of Social Security benefits whenever there is a delay in raising the debt limit. In 1997, the Social Security Administration (SSA) implemented a new policy to vary the payment of monthly benefits based on each beneficiary’s date of birth.[20] Read in combination, these two changes could have the unintended effect of funding the rest of the government until the Social Security trust funds are exhausted should Congress fail to increase the debt limit after other extraordinary measures have been exhausted.

Figure 2 shows the various categories of Social Security beneficiaries and when their benefits are paid throughout the month.

Figure 2: Monthly Payment Date for Social Security Benefits

Unlike previous episodes in which the Treasury could redeem debt held by the Social Security trust funds and borrow an equivalent amount from the public to pay benefits on the third day of each month, benefits are now paid throughout the month.[21] To ensure every Social Security beneficiary is paid on time, and the benefits are cleared through the banking system, the government would need to ensure the Treasury General Account (TGA) is never overdrawn. One way to achieve that result would be to redeem enough Social Security trust fund debt to cover all the government’s bills each month.

Given the current balance in the Social Security trust funds ($2.8 trillion), the government would be able to ensure the payment of Social Security benefits – and fund the rest of the government as well – for a considerable period without increasing the debt limit.[22] Admittedly, Congress did not intend this result when it limited the disinvestment of the Social Security trust funds to the purpose of paying benefits. However, the Treasury has suggested that it lacks the ability to selectively pay some bills and not others (except perhaps principal and interest on the debt as noted above). If this is true, then one way to ensure Social Security benefits are paid on time – as Congress intended – is for the Treasury to pay all its bills on time.

As long as there is a positive balance in the Social Security trust funds, the Treasury Secretary has both the authority and the obligation to pay Social Security benefits. Even though Congress intended to prohibit the use of the trust funds to circumvent the debt limit, Congress also intended to allow the disinvestment of the trust funds when necessary to pay benefits. If Congress fails to increase the debt limit before the traditional extraordinary measures have been exhausted, the Treasury will be forced to choose between two conflicting priorities. Disinvesting the trust funds could have the unintended effect of implicitly creating another extraordinary measure to temporarily fund the government until the debt limit is increased; whereas the failure to disinvest the trust funds could have the effect of delaying the payment of Social Security benefits.

Conclusion

Establishing a limit on the total amount of government debt allows Congress to maintain control over its constitutional authority to borrow money. Failure to balance the budget means increasing the debt limit is necessary to avoid default and honor the government’s previous commitments. Among those commitments is the timely payment of scheduled Social Security benefits. Current law allows the Treasury to make these payments by disinvesting the trust funds whenever the debt limit increase is delayed. However, utilizing this escape clause to pay scheduled benefits could have the unintended effect of temporarily funding other government programs until the Social Security trust funds were exhausted or the debt limit was increased.

[2] Life After Default | CEA | The White House; The Debt Ceiling: An Explainer | CEA | The White House

[3] P.L. 104-121.pdf | (congress.gov); The escape clause also applies to the Medicare HI and SMI trusts funds, which are not included in this analysis as that would not change the overall conclusions.

[4] The Debt Limit: History and Recent Increases (congress.gov)

[5] Debt Position and Activity Report | TreasuryDirect

[6] Federal Debt: A Primer | (cbo.gov)

[7] Social Security and the Federal Budget – The Concord Coalition

[8] Federal Borrowing and Debt (whitehouse.gov)

[9] FAQs About the Public Debt | TreasuryDirect

[10] Debt Limit | U.S. Department of the Treasury; The Treasury is required to pay any forgone interest and restore the funds to the balance that would have existed without the extraordinary measures.

[11] Reaching the Debt Limit: Background and Potential Effects on Government Operations | (congress.gov); OIG Debt Limit Response (Final) | (treasury.gov)

[12] Monthly Treasury Statement | (treasury.gov); Fiscal Years run from October to September

[13] A standard deviation (Stdev) is the range that includes roughly two-thirds of the observations in each monthly dataset.

[14] FOMC Conference Call Transcript, August 1, 2011 | (federalreserve.gov)

[15] P.L. 104-121.pdf | (congress.gov)

[17] #142: Trust Fund Investment Policies and Practices | (ssa.gov)

[18] AIMD-96-130 Debt Ceiling: Analysis of Actions During the 1995-1996 Crisis | (gao.gov)

[19] P.L. 104-121; Social Security Act §1145 (ssa.gov)

[20] SSA – POMS: GN 02402.002 – Direct Deposit for Title II and Title XVI

Continue Reading