I. Policy Proposals – Relative to What?

Three times every year the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) produces a “baseline” of its budget outlook for the coming decade. As described by CBO, the baseline represents its “best judgment of how the economy and other factors would affect federal spending and revenues if current laws and policies remained in place.”[1]

I. Policy Proposals – Relative to What?

Three times every year the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) produces a “baseline” of its budget outlook for the coming decade. As described by CBO, the baseline represents its “best judgment of how the economy and other factors would affect federal spending and revenues if current laws and policies remained in place.”[1]

The nonpartisan CBO baseline is the required starting point for assessing the potential budgetary impact of congressional legislation. For this reason, and because of its neutrality, the CBO baseline is also the appropriate starting place for assessing the spending and tax proposals of the presidential candidates.

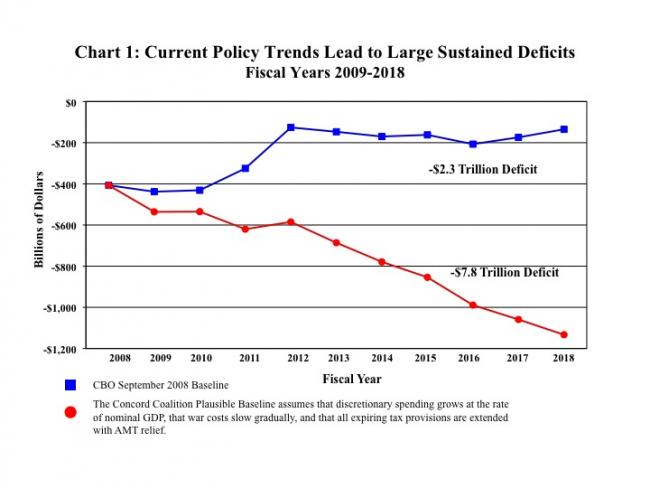

In its most recent update, issued on September 9, 2008, CBO projected a deficit of $407 billion in Fiscal Year 2008 or 2.9 percent of Gross Domestic Product (GDP). This is more than twice the $161 billion deficit (1.2 percent of GDP) recorded in 2007. Much of the increase is due to the slowing economy and the stimulus checks that the government sent out earlier in the year. Even so, the deficit now seems to be on an upward trend.The deficit is projected to reach $438 billion in Fiscal Year 2009. Over the coming decade (2009-2018), CBO projects deficits for every year, totaling $2.3 trillion.

In an ominous sign of things to come, CBO projects that the cost of Social Security, Medicare, and Medicaid will grow from 8.9 percent to 11.0 percent of GDP over the 10-year outlook – a 24 percent increase. As a result, these three programs, which consume 42 percent of the budget in 2007, will consume 50 percent within 10 years. Over the longer-term, CBO confirmed that the budget remains on an unsustainable path.

Budget projections over the coming 10 years are unusually complicated by a number of factors – some on the spending side andsome on the revenue side.

On the spending side, projections are complicated by the treatment of military operations in Iraq and Afghanistan. According toCBO, Congress has approved $186 billion for 2008 and $68 billion so far for2009. The baseline assumes that the level of spending for these operations will continue at around its current level adjusted for inflation, as it assumes for all appropriations. The spending projections also leave out any estimates for cash infusions that may be needed to rescue Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

Projections on the revenue side of the budget are complicated by two factors; the scheduled expiration by 2011 of the tax cuts enacted since 2001 and the growing toll of the Alternative Minimum Tax (AMT), which if not adjusted will apply to roughly eight times as many taxpayers by 2010 as it does today because it is not indexed for inflation.Congress has been dealing with this problem by enacting one-year “patches” that are getting increasingly expensive because the number of taxpayers who would otherwise pay the tax increases every year.

For many years, The Concord Coalition has produced a “plausible” scenario using CBO numbers[2]to show what the budget outlook would look like if spending and tax policies are adjusted to reflect recent trends rather than the official baseline. These adjustments:

- Assume a phase-down, but not a phase-out, of funding for Iraq and Afghanistan.

- Assume that regular appropriations grow at the same rate as the economy.

- Assume that all expiring tax cuts are extended.

- Assume continuing relief from the AMT by adjusting it for inflation.

- Include debt service cost on the above changes due to added borrowing.

Under that scenario, deficits would total $7.8 trillion over the 10-year period from 2009 to 2018 (see Chart 1). As a percentage of the GDP, deficits would steadily rise from 2.9 percent to 5.1 percent by 2018 and average 4.2 percent over the 10-year period. The government’s debt held by its outside creditors (debt held by the public) would rise from 38 percent of GDP to 60 percent by 2018. Interest on this debt, which is an expense borne by tax payers, would climb from about $240 billion this year to $638 billion by 2018.

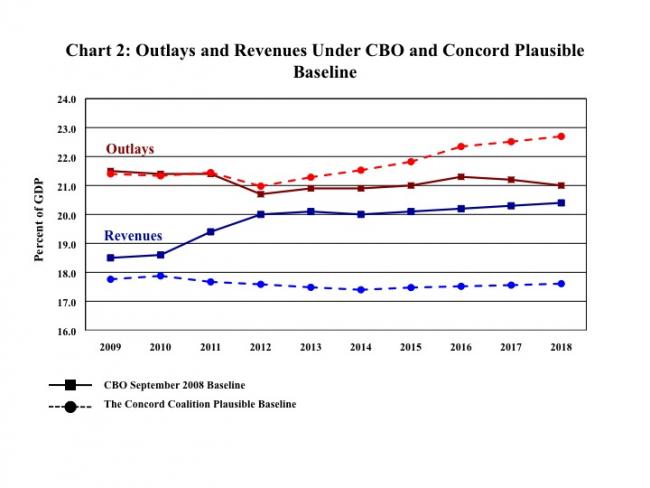

The starkest difference between the two scenarios is in their assumptions of total revenue levels (see Chart 2). That difference grows from 0.7 percent of GDP in 2009 to 2.8 percent of GDP in 2018. In dollars, the revenue gap between the CBO baseline and the Concord baseline in 2018 is $630 billion. The outlay difference between the twoscenarios does not grow greater than 0.7 percent of GDP until 2015 and expands to 1.7 percent of GDP by 2018, a difference of $368 billion.

Creating a “plausible baseline” is meant to warn against the dire consequences of failing to change course. It is not meant to establish an acceptable standard against which policy proposals should be measured. Unfortunately, that appears tobe what the presidential candidates are doing. Instead of measuring the budgetary impact of their respective budget plans against the official baseline, they argue that their plans should instead be measured against themuch less favorable outlook shown in Concord’s plausible scenario or similar projections.

The political logic behind this baseline switch is obvious. Measured against current law (i.e., the officialCBO baseline) the candidates’ plans would significantly expand the deficit. Measured against a much worse scenario such as Concord’s plausible baseline, their plans show improvement. They can thus claim to be “lowering” the deficit when, in fact, it might remain exactly where it is now or even go up.

The baseline is a powerful factor in setting expectations. If the bar is lowered it is easier to clear. If educational standards are lowered, more students will receive a passing grade but they will not be any smarter. Similarly, lowering the bar for what passesas “fiscal discipline” may improve the scoring of tax and spending legislation but it won’t improve the budget outlook and may contribute to further erosion.

II. The Important Role of Pay-As-You-Go (PAYGO) Budgeting

Before moving on to the economic significance of baselines, it is important to consider the role of paygo budget rules in promoting the necessary trade-offs to achieve a brighter outlook. Last year, Congress took a step toward restoring fiscal discipline and preventing the daunting long-term outlook from getting any worse by adopting paygo budget rules in the House and Senate. These rules require that any legislation to lower revenues or expand entitlement spending – relative to the baseline – be offset with corresponding revenue increases orspending cuts.

As Congress enters the final weeks of its current session, the House and Senate face a key test of their commitment to paygo when they consider legislation providing a one-year “patch” of relief from the AMT and extending a number of expiring tax breaks. The next Congress and whoever is elected president this year will face even greater paygo challenges when an array of expiring tax cuts are due to expire (“sunset”) on December 31, 2010.

They will face a choice between paying our own way, which we clearly have the capacity to do, or continuing to run up a legacy of debt for future generations of Americans to pay off. Expressing support for paygo in the abstract is relatively easy. The difficult part is actually making the hard choices and enacting them into law.

The budgetary consequences of sticking to paygo or not over the next 10 years alone are enormous. Under current law, the tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 are scheduled to expire. Moreover, current law does not assume further relief from the AMT. Thus, the revenue that comes from these provisions is assumed in the CBO baseline. Waiving paygo for these popular items would decrease revenues and increase the deficit by $5.1 trillion over 10 years, including added debt service costs.

A recurring debate regarding paygo is whether assuming baseline revenues from the expiring tax cuts constitutes a “tax increase.” Thisis more a matter of political positioning than it is of budgeting. Allowing some or all of the tax cuts to expire does indeed mean that certain tax rates would go up from where they are now. That, however, would not be the result of Congress raising taxes. It would be the result of “sunsets” that were included when these tax cuts were originally enacted to avoid the level of fiscal scrutiny that paygo is designed to ensure. Congress can use reserve funds to authorize tax relief, but require that the legislation implementing it comply with paygo by finding offsetting revenues elsewhere or by reducing mandatory spending. Going through this process forces an explicit trade-off between spending, taxes and debt, which is exactly the priority-setting exercise that the budget process should be.

No budget rule will be effective if it is not accompanied by a commitment to enforce it. Thus, it is critical that Congress and the presidential candidates resist pressure to weaken paygo by exempting politically popular items. Looking ahead, many tax and spending initiatives will need to be scaled back to fit within the amount of available offsets. If Congress maintains its commitment to paygo when the going gets rough, it will send a powerful signal that Washington has found the resolve to take its long-term fiscal problems seriously. By contrast, a decision to waive paygo will signal business as usual – casting in doubt the credibility of lawmakers to make tough decisions on spending as well as taxes.

III. The Longer-Term Outlook Under the CBO’s Baseline

CBO’s updated budget and economic outlook contains projections that extend only over the next 10 years. Their most recent longer-term analysis – with budget projections that extend over 75 years – was published in December 2007. In that analysis, CBO focuses on two scenarios, a “baseline extended” scenario that closely tracks the 10-year CBO baseline, and an “alternative fiscal scenario” that adds in the cost of policy alternatives similar to Concord’s plausible baseline discussed above.

The baseline scenario assumes a level of revenues consistent with current law: the 2001-03 tax cuts expire at the end of 2010 or any extensions are offset consistent with paygo, and Medicare growth is restrained by current-law rules that sharply reduce reimbursement rates for physicians.

Under the alternative scenario, the 2001-03 taxcuts and relief from the AMT are permanently extended without offsets (i.e., deficit financed) and Medicare spending grows more rapidly than undercurrent law (consistent with recent history).

CBO’s long-term budget projections are “static” in that they do not account for the macroeconomic feedback effects associated with the different fiscal scenarios. CBO assumes a path of real economic (GDP) growth that derives from their longer-term macroeconomic projections but is independent of the potential economic effects associated with the different tax and spending policies that are implicit in the two scenarios. Thus, the budgetary projections are based on the same path of economic growth.

Based on this static projection, CBO estimates that the baseline scenario would result in deficits rising from 1.2 percent of GDP in fiscal year 2007 to4.6 percent of GDP by 2050, and to 18.1 percent of GDP by 2082. Under the alternative scenario, the fiscal outlook would be much worse. Deficits would grow to 22.5 percent of GDP in 2050, and to 54.5 percent of GDP by 2082.

IV. How the Policy Scenarios Matter for Economic Growth and the Intergenerational Distribution of Income

Although CBO does not incorporate macroeconomic feedback effects into their long-term budget projections, their report still recognizes the two scenarios would lead to significantly different economic results under the different paths.

As CBO explains (emphasis added):

CBO’s two long-term budget scenarios would have different effects on the economy. Under the extended-baseline scenario, outcomes early on would be considerably more auspicious, but under both scenarios, the growth of debt would eventually accelerate as the government attempted to finance its interest payments by issuing more debt-leading to a vicious circle in which it issued ever-larger amounts of debt in order to pay ever-higher interest charges. In the end, the costs of servicing the debt would outstrip the economic resources available for covering those expenditures.

Sustained and rising budget deficits would affect the economy by absorbing funds from the nation’s pool of savings and reducing investment in the domestic capital stock and in foreign assets. As capital investment dwindled, the growth of workers’ productivity and of real wages would gradually slow and begin to stagnate. As capital became scarce relative to labor, real interest rates would rise…[3]

To analyze the different economic effects of the two scenarios, CBO compares them to a model under which today’s deficit level is held constant over thelong-term. They are then able to deduce the following rates of real economic growth over the 2007-2040 period:

| CBO Long-Term Policy Scenario (Dec. 2007) | Real GDP in 2040 (2000 $) | % Growth from 2007 |

| Extended Baseline | $24.3 trillion | 108% |

| Alternative Fiscal | $21.2 trillion | 81% |

Even under the rather dire alternative scenario, a “stay the course”scenario of sorts where debt to GDP reaches nearly 200 percent by 2040, the economy is still larger in real terms. While it will surely be smaller thanunder the extended-baseline, current-law scenario, today’s children would still enjoy an economy 81 percent larger in the prime of their working lives than we do today.

But that is not the end of the story. To evaluate the intergenerational “fairness” of this outcome, two questions remain: (i) how does this translate into per capita terms? After all, the real economy has to grow in dollar terms just to keep up with population growth, otherwise people will not be better off at all. And (ii) how does an 81 to 108 percent growth in real GDP over the next 33 years (a “generation”) compare with the growth in real GDP that has been experienced over 33-year periods in the past?

Referencing the historical real GDP data and the historical population numbers, and going back 33 years to 1974 (when today’s prime-age working adultswere children), and back another 33 years before that to 1941 (when the parents of today’s prime-age working adults were children), we can compare per capita real GDP growth rates:

| 33-Year Period: | % Growth in Real Per Capita GDP |

| 1941-1974 | 123% |

| 1974-2007 | 89% |

| 2007-2040, under CBO’s extended baseline | 60% |

| 2007-2040, under CBO’s alternative fiscal scenario | 39% |

Intergenerational fairness may be in the eye of the beholder, and 39 percent is still bigger than zero. But 39 percent is substantially less than 89 percent (for the prior generation) or 123 percent (for the generation prior to that), and considerably less than 60 percent (the baseline-extended scenario where paygo is enforced).

But even the relatively unimpressive 39 percent growth in per capita real GDP under CBO’s alternative scenario is optimistic. Although it accounts for the economic effects of a growing budget deficit (that reaches more than half of GDP in 2082[4]), the 39 percent growth does not account for the fact that eventually the gap will have to be closed or the economy will “blow up” – at least in a simulation sense – and that eventually will involve tax increases and/or spending cuts that would further cut into any measure of economic well being.

CBO’s report includes a section speaking directly to this issue, called “What Are the Costs of Delaying Action on the Budget?” [5] In that section, CBO examines how much of a tax increase or spending cut would be needed to close the gap under the alternative scenario depending on when that action was eventually taken. CBO does not do this analysis for the baseline scenario because it does not have to. The baseline scenario already has built into it a way of closing the gap over the next 25-50 years: letting revenues increase substantially from almost 19 percent in 2007 to 23.5 percent by 2050. In contrast, under the alternative scenario revenues remain in the 18.5 to 19.5 percent of GDP range through 2050, failing to keep up with spending growth. The longer corrective steps are put off, the larger the adjustment that is needed.

Delaying action allows us to temporarily enjoy a higher level ofgovernment spending and/or more tax cuts, and a higher GDP, but this just postpones the eventually higher cost which on net leaves us worse off because economic growth is unable to keep up fully with the compounded interest.

As economists continuously point out, there is no free lunch. The 39 percent growth in per capita, real GDP is only before the bill comes due. If we assume that we proceed with the alternative scenario, in which tax cuts are extended without offsets, then we enlarge the deficit and increase the drag on our economy due to interest payments and reduced national saving. But if on top of that, we assume that the next generation might finally wise up before the economy collapses, or be forced to take action by nervous lenders, and would take action to close the fiscal gap by 2040, then they would have to pay higher taxes and/or put up with lower spending starting in 2040. How much would those higher taxes or reduced benefits cut into that already-too-low 39 percent real growth in their per capita average incomes?

According to CBO, under the alternative scenario, in order to close the fiscal gap, tax revenues would have to come up permanently by 6.9 percent of GDP if action began in 2008, but by a much larger 15.2 percent of GDP if action was delayed until 2040. Interpreting these tax increases as shares of per capita income that would have to be “taxed away” eventually when the bill was paid, we obtain an even more dire result for the alternative scenario:

| 33-Year Period: | % Growth in Real Per Capita GDP |

| 2007-2040, under baseline extended | 60% |

| 2007-2040, under alternative fiscal scenario, not paid for | 39% |

| 2007-2040, under alternative fiscal scenario, if cost offset starting 2008 | 39% |

| 2007-2040, under alternative fiscal scenario, if cost offset starting 2040 | 18% |

Note that under the no offset scenario, it is economic growth after 2040 that would be harmed. Under the case where costs are offset starting in 2008, growth over 2007-2040 is still 39 percent, but there would be no more postponed tax increases or spending cuts needed after that over the 75- year window.

V. How the Presidential Candidates Talk About the Policy Scenarios and Choose Their Baselines

Senators John McCain (R-AZ) and Barack Obama (D-IL) have very different visions of fiscal policy going forward, but they share a common desire to have their proposals evaluated relative to relaxed standards rather than the current-law baseline. Of course, relative to an alternative baseline that implies deficits of almost $8 trillion over 10 years, the candidates’ proposals look much more fiscally responsible than they do relative to the official CBO baseline (with a 10-year deficit of “just” $2.3 trillion).

What are the implications of the candidates’ fiscal policy proposals relative to these baselines? Both Senator McCain and Senator Obama have suggested deficit targets for 2013, while outlining their tax policy plans in enough detail for the Tax Policy Center[6]to estimate their cost. Our analysis simply puts these pieces together.

Revenues and Outlays Under the Obama Proposals

The Tax Policy Center’s analysis shows that under the Obama tax proposals federal revenues in 2013 would be 18.1 to 18.3 percent of GDP (based on descriptions by campaign staff and “stump speeches”, respectively). This would leave revenues right around the 40-year historical average of 18.3 percent ofGDP, but well below the current-law baseline of 20.1 percent of GDP in 2013. This, in effect, represents a net tax cut.

Compared with the alternative baselines that extend expiring tax cuts, the Obama tax proposals raise revenue (In 2013, those baselines have revenues of 17.7 percent (Tax Policy Center) or 17.5 percent (Concord Plausible)). One reason they may prefer this baseline even though it could be called a “tax increase” is that it would allow Obama to claim expiring tax cuts as an offset to new initiatives, which would not be allowed under current law because that revenue is already assumed into the CBO baseline – it is not new revenue and thus not an offset to new spending or other tax cuts.

In terms of a deficit target, the Obama campaign has publicly expressed a goal of achieving a unified deficit that is below the current nominal level by2013. With a current (FY2008) unified deficit of $407 billion (from CBO’s new forecast), this would imply an Obama deficit target of around 2.2 percent of GDP in 2013.

Coupled with the Tax Policy Center estimates of 2013 revenues under the Obama tax proposals, this implies outlays of 20.3 to 20.5 percent of GDP in 2013-which is below both CBO current-law baseline outlays of 20.9 percent and Concord plausible-baseline outlays of 21.3 percent.

So relative to current law, the Obama campaign is proposing a tax cut of around 2.0 percent of GDP and a smaller cut in spending of around 0.5 percent of GDP, resulting in that 2.2 percent of GDP deficit. This is considerably larger than the current-law deficit of 0.8 percent. Relative to an extension of current policy, which produces a deficit of 3.8 percent of GDP in 2013, the Obama campaign is proposing a tax increase in the 0.5 to 1.0 percent of GDP range and a cut in spending of around 1.0 percent of GDP-both actions working to reduce the deficit compared with the Concord plausible baseline. The question remains whether such a reduction in the level of outlays from the current policy stance is consistent with the various spending-side initiatives the Obama campaign has in mind. And, in any event, maintaining a status quo deficit of about 2 percent of GDP would do nothing to address the unsustainable long-term outlook that already exists.

Revenues and Outlays Under the McCain Proposals

According to the Tax Policy Center, under the McCain tax proposals federal revenues in 2013 would be between 16.0 and 17.4 percent of GDP (the “stump speeches” suggesting the lower number). Thus, compared with revenues under either the current-law baseline (20.1percent of GDP) or the alternative scenarios (17.5 to 17.7 percent of GDP according to Concord and the Tax Policy Center, respectively), the McCain tax proposals lose substantial amounts of revenue.

In terms of a deficit target, the McCain campaign has publicly expressed agoal of balancing the federal budget by 2013-i.e., achieving a unified budget deficit of zero percent of GDP in 2013. This goes beyond the fiscal discipline under the current-law baseline,where a small deficit (0.8 percent of GDP) remains in 2013.

Coupled with the Tax Policy Center estimates of 2013 revenues under the McCain tax proposals, this implies outlays of 16.0 to 17.4 percent of GDP in 2013. Compared with the CBO current-law baseline, this is a cut in spending in the 3.5 to 4.9 percent of GDP range. Compared with the Concord plausible baseline, this represents a cut in spending in the 3.9 to 5.3 percent of GDP range. It is difficult to imagine how cuts that large are feasible given that all of discretionary spending iscurrently 7.9 percent of GDP.

Effect of Candidates’ Tax Proposalson Revenues, Their Deficit Targets, and Implied Outlays, in 2013

VI. Conclusion: Budgeting As If It Matters

The deficit status quo is unacceptable. Not only should policymakers strictly enforce paygo, they must also begin taking steps to close the long-term unsustainable gap between revenues and promised benefits for Medicare and Social Security. The fact that we’ve had higher deficits before as a percentage of the economy and managed to dig our way out offers no reason for complacency.

Circumstances are very different from the late 1980’s and early 1990’s. The end of the Cold War allowed us to shrink defense expenditures from 6 percent of GDP in 1985 to 3 percent by 2000. While defense spending has not gone back to Cold War proportions, it has risen back to over 4 percent of GDP and is not likely to go down significantly in the near term. Our national saving rate has plummeted from over 8 percent to essentially zero, and the portion of our debt held by foreign lenders has shot up from less than 20 percent to nearly 50 percent. More fundamentally, the boomers’ retirement in those days was a generation away. Now, the first boomers have already begun to qualify for Social Security. In total, we face a much more urgent, and difficult, situation than we did 20 years ago.

Balancing the budget is not an end in and of itself, but a means to an end. A balanced budget provides evidence of sustainable fiscal policy and responsible governance. Deficits accumulated over the last seven and a half years alone (since January 2001) total nearly $2.1 trillion[7]-nearly$7,000 for every man, woman and child living in the United States today. Explanations for those deficits abound (recession, terrorism, war, natural disasters, etc.). Yet, it is relevant to note that more than half of the deterioration in the budget outlook since January 2001 (when CBO projected $5.6trillion in budget surpluses for 2002-2011) results from enacted legislation, which policymakers control.

Over the next 10 years there will be two presidential elections and five congressional elections. Without a firm commitment to fiscal discipline backed up by budget enforcement rules, deficits are more likely to increase than decrease. Budget process tools, such as statutory limits on discretionary spending and paygo, helped policymakers achieve a balanced budget in 1998 and for three years thereafter. The need for such rules is even more acute now.

Expiration of the 2001 and 2003 tax cuts at the end of 2010 likely provides our first test of fiscal courage. It does not require letting all the tax cuts expire, and it does not require raising marginal tax rates to pay for the tax cuts we choose to keep. But whatever tax cuts we do want to keep, we ought to be willing to pay for them in ways that keep revenues at baseline levels (or make up the difference with spending cuts), and in ways that make economic sense-both for today’s economy and especially for our children’s economy. Having the next Administration and the next Congress stick with (and maybe even strengthen) pay-as-you-go budget rules would be a great step toward making that happen.

What is striking about the current budget debate is the obvious lack of any consensus within the Congress about priorities and the goals of fiscal policy. Whereas successive deficit reduction legislation in the 1980s and 1990s focused on revenue increases as well as spending restraint, the current, exclusive emphasis on spending cuts threatens to undermine serious efforts to address fiscal imbalance. The presidential candidates currently suffer from this same, unrealistic fiscal policy strategy, proposing levels of tax cuts that seem inconsistent with deficit reduction, given their other economic policy goals. We can only hope that when the next president takes office, some of these campaign promises will give way to economic reality.

Pressures are mounting throughout the economy-on private firms as they attempt to address problems with their global competitiveness including the cost of health care and retirement benefits for their employees; on baby boomers, many of whom are balancing the need to support children as well as aging parents; and on state and local governments that are struggling with their own fiscal gaps.

The ability of the federal government to be the “insurer of last resort” and to be in a position to address emerging national needs is compromised by the policymakers’ inability to confront the budget’s shortcomings. That injects uncertainty and instability into the economy, when what is required is decisive leadership. The result is fiscal insecurity for both current and future generations.

Appendix: Backup Data for Concord Plausible Baseline

[1]CBO, The Budget and Economic Outlook Fiscal Years2008-2018, January 2008, p.5.

[2] CBO, As derived from Table 1-8 on Pp. 20-21 in The Budget and Economic Outlook: An Update (September 2008), Congressional Budget Office.

[3] CBO, The Long-Term Budget Outlook (December 2007), p. 11

[4] CBO, The Long-Term Budget Outlook (December 2007), p. 5

[5] CBO, The Long-Term Budget Outlook (December 2007), p. 15-17

[6] Tax Policy Center’s “An Updated Analysis of the 2008 Presidential Candidates’ Tax Plans” (August 2008)

[7]From Monthly Statements of the Public Debt, U.S. Department of the Treasury.

Continue Reading