By Richard Jackson, Global Aging Institute

As 2021 begins, America is beset by a host of urgent challenges. At home, the nation remains deeply divided in the wake of a bitterly contested election. Abroad, authoritarianism is on the rise and liberal democracy in retreat. Meanwhile, the pandemic continues to endanger both our health and our economy.

At such a juncture, it may seem unreasonable to ask America’s leaders to focus on the longer-term challenges posed by the aging of the population. Yet not to focus on them would be a grave disservice to posterity. On its current demographic and economic trajectory, America is headed toward a future of permanently slower growth, crushing fiscal burdens, and greatly diminished opportunity. This is not the future that any of today’s adults, Democrat or Republican, want to bequeath to their children and grandchildren. Yet without concerted action, it is almost certainly the future they will inherit.

In this issue brief, we lay out five imperatives for an aging America. The first is to limit the extent of population aging by increasing the fertility rate and net immigration above today’s low levels. The second is to offset the demographic drag of population aging on economic growth by encouraging longer work lives and leveraging the productive potential of the elderly. The third is to control the growth in health-care spending, which is the main driver of long-term structural budget deficits. The fourth is to stabilize the national debt as a share of GDP, since, modern monetary theorists to the contrary, its continued rise threatens to exact a heavy toll on future generations of workers and taxpayers. The fifth is to resist the rising tide of protectionism, which if unchecked will deprive an aging America of the immense benefits that can flow from open global capital markets and labor markets.

None of these goals will be easy to achieve, and some may prove to be elusive. Yet all deserve the serious attention of policymakers.

Increase the Fertility Rate and Net Immigration

The aging of the U.S. population is inevitable. Like other developed countries, as well as a growing number of emerging markets, America is passing through the so-called demographic transition, the shift from high fertility and high mortality to low fertility and low mortality that accompanies development and modernization. As the transition progresses, population growth rates slow and age structures shift upwards. The degree of population aging that America experiences, however, is not inevitable.

Until recently, the United States was a demographic outlier among its developed world peers. After dipping well beneath the 2.1 replacement rate needed to maintain a stable population from one generation to the next in the 1970s, the U.S. fertility rate partially recovered as Boomers finally got around to starting families. From the beginning of the 1990s until the Great Recession of 2008-09, it averaged 2.0, higher than the rate of any other developed country except Iceland, Israel, and New Zealand. Together with substantial net immigration, America’s relatively high fertility rate seemed to ensure that it would remain the youngest of the major developed countries. It also seemed to ensure that America would still have a growing workforce, even as those in other developed countries stagnated or declined. The U.S. outlook was so strikingly different from that in the rest of the developed world that the demographer Nicholas Eberstadt coined the term “demographic exceptionalism” to describe it.[1]

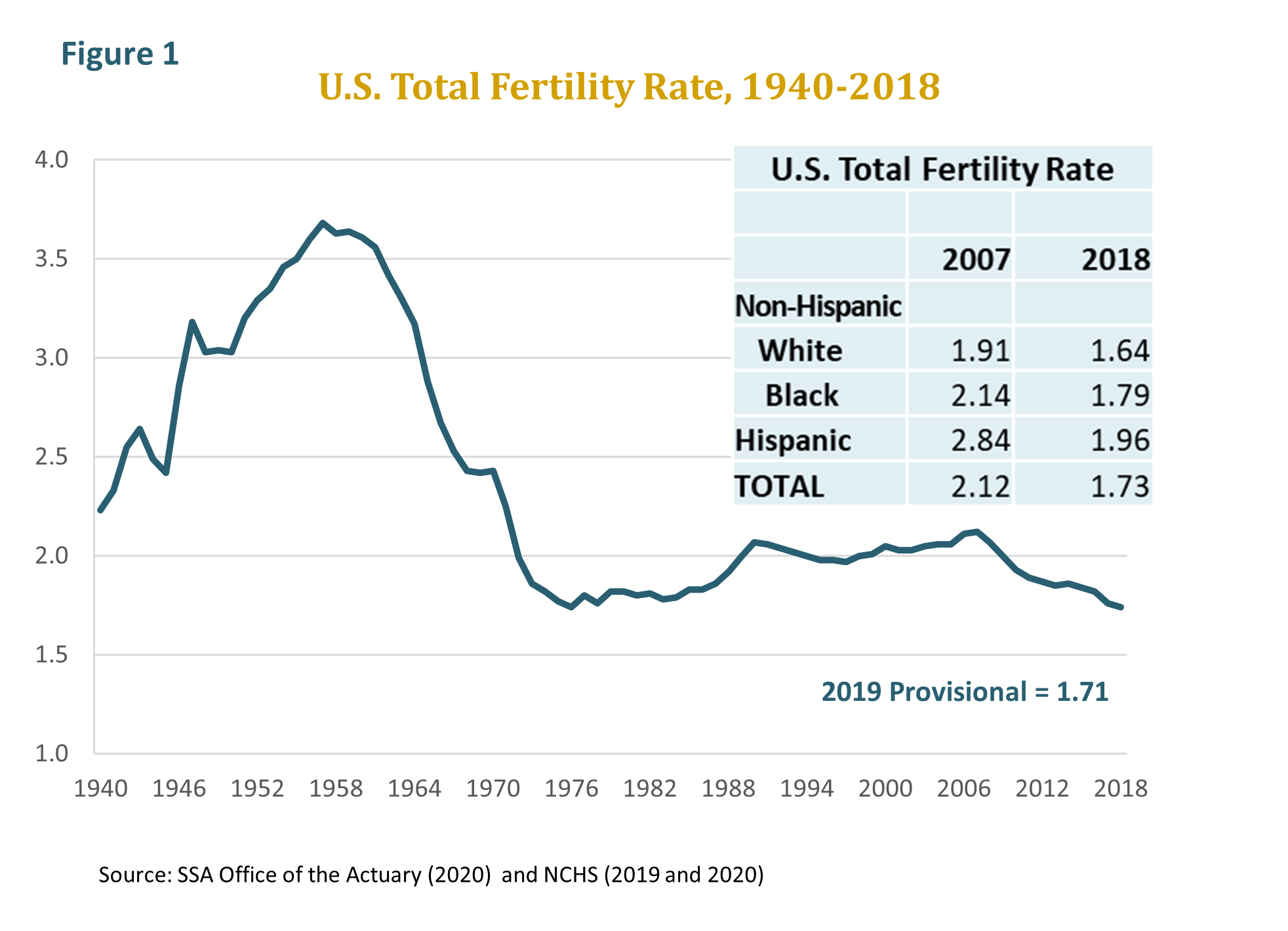

Over the past decade, however, America has begun to look much more like a typical developed country. The U.S. fertility rate has been falling steadily since 2008, and as of 2019 stood at 1.7, the lowest level on record. (See figure 1.) Initially, many demographers assumed that the decline was largely a “tempo effect,” and that Millennials were merely postponing family formation rather deciding to have fewer children. But as yet there is no clear sign of an uptick in the age-specific fertility rates of women in their early and mid-thirties, which one would expect to have seen by now if this were the case. And if that uptick has not yet happened, we should not expect it anytime soon. One of the things that history teaches about pandemics is that they typically depress fertility rates, at least for a while.

To make matters worse, net immigration, which in the near term acts much like a higher fertility rate, has also declined After rising during the 1990s and plateauing in the early 2000s, net immigration fell in the wake of the Great Recession, recovered again in the mid-2010s, then plunged. As of 2019, on the eve of the pandemic, it stood at barely half the level it had been just five years before.

As we explained in a previous issue in this series (“America’s Demographic Future,” Spring 2020), these developments, if not reversed, will spell the end of U.S. demographic exceptionalism. To be sure, the decline in the fertility rate over the past decade is not large enough to put America on the ruinous demographic trajectory of a Greece, Italy, Spain, Japan, or South Korea, in the last of which by 2050 more people may be turning 90 each year than being born. But unless the fertility rate rebounds, the United States will age significantly more than is suggested by current Census Bureau or Social Security Administration projections, which do not fully factor in the recent decline. Rather than stabilizing at around 22 or 23 percent when the last of the Boomers have crossed the threshold of old age, the elderly share of the population would keep rising, eventually approaching 30 percent. If this happens, economic growth will also slow more and fiscal burdens rise further than is currently projected.

The causes of the recent decline in the U.S. fertility rate are not yet entirely understood. It may be that many Millennials simply want smaller families, and to the extent this is the case there is little that public policy can or should do to encourage more births. But it may also be true that many Millennials would like to have more children than they currently are. We know from cross-country analyses that fertility rates are sensitive to how easy or difficult it is for young people to launch careers, establish independent households, and balance work and family responsibilities. All of this has become much more difficult for Millennials than it was for Xers or Boomers at the same age, which suggests that initiatives on many policy fronts, from easing college loan burdens to providing for subsidized daycare, could make a difference.

The causes of the recent decline in the U.S. fertility rate are not yet entirely understood. It may be that many Millennials simply want smaller families, and to the extent this is the case there is little that public policy can or should do to encourage more births. But it may also be true that many Millennials would like to have more children than they currently are. We know from cross-country analyses that fertility rates are sensitive to how easy or difficult it is for young people to launch careers, establish independent households, and balance work and family responsibilities. All of this has become much more difficult for Millennials than it was for Xers or Boomers at the same age, which suggests that initiatives on many policy fronts, from easing college loan burdens to providing for subsidized daycare, could make a difference.

With the prospects for raising the fertility rate so uncertain, reversing the recent decline in net immigration becomes all the more important. It is true that the decline is in part the result of demographic trends that are likely to prove enduring, including slower population growth in many traditional sending countries in Latin America (less immigration “push”) and slower economic growth in the United States (less immigration “pull”). But net immigration is nonetheless much more responsive to policy change than the fertility rate is, and policy has become more restrictive. There is considerable room for principled disagreement on matters of immigration policy, from whether there should be a path to citizenship for illegal immigrants to whether the current system, which is based on family reunification, should be replaced with a skills-based system. What is not in question is that an aging America would benefit from increased immigration. In the past, when we had replacement-level fertility, immigrants were what kept the workforce growing. In the future, they may be all that keeps it from shrinking.

Encourage Longer Work Lives

Working longer as America ages is both natural and necessary. It is natural because life spans and health spans have risen dramatically since today’s retirement institutions were first put in place in the early postwar decades. And it is necessary because an equally dramatic slowdown in economic growth, itself largely a consequence of population aging, is rendering those institutions unsustainable.

As the smaller cohorts born since the end of the postwar Baby Boom have climbed the age ladder, the growth rate in U.S. employment has decelerated, from 2.2 percent per year between 1965 and 1985, as Boomers came of age and women first entered the workforce en masse, to 0.7 percent per year between 2000 and 2019. By the 2030s and 2040s, the CBO projects that employment growth will have sunk to an average of just 0.3 percent per year, an outcome that could easily pull down real GDP growth to between 1.0 and 1.5 percent per year, just one-third to one-half of its postwar average.

As we explained in a previous issue in this series (“The Case for Longer Work Lives,” Summer 2020), longer work lives could substantially offset the demographic drag that slower growth in the population in the traditional working years would otherwise have on economic growth. GAI calculates that if the employment rate of adults aged 55 to 74, after adjusting for the higher incidence of disability at older ages, were to gradually increase to the “prime-age” rate for adults aged 25 to 54, it would boost employment and GDP growth by 0.4 percentage points. By 2050, GDP would be nearly 15 percent larger than it would be if employment rates at older ages did not rise.

There would be other benefits as well. In fiscal terms, longer work lives would generate extra tax revenue that could help to alleviate the rising burden of old-age benefit spending. In individual terms, they would improve retirement security by increasing the number of years during which workers save for retirement while decreasing the number of years of retirement that need to be financed. A growing literature, moreover, concludes that continued productive engagement has a large positive effect on the physical health, cognitive function, and emotional well-being of older adults.[2]

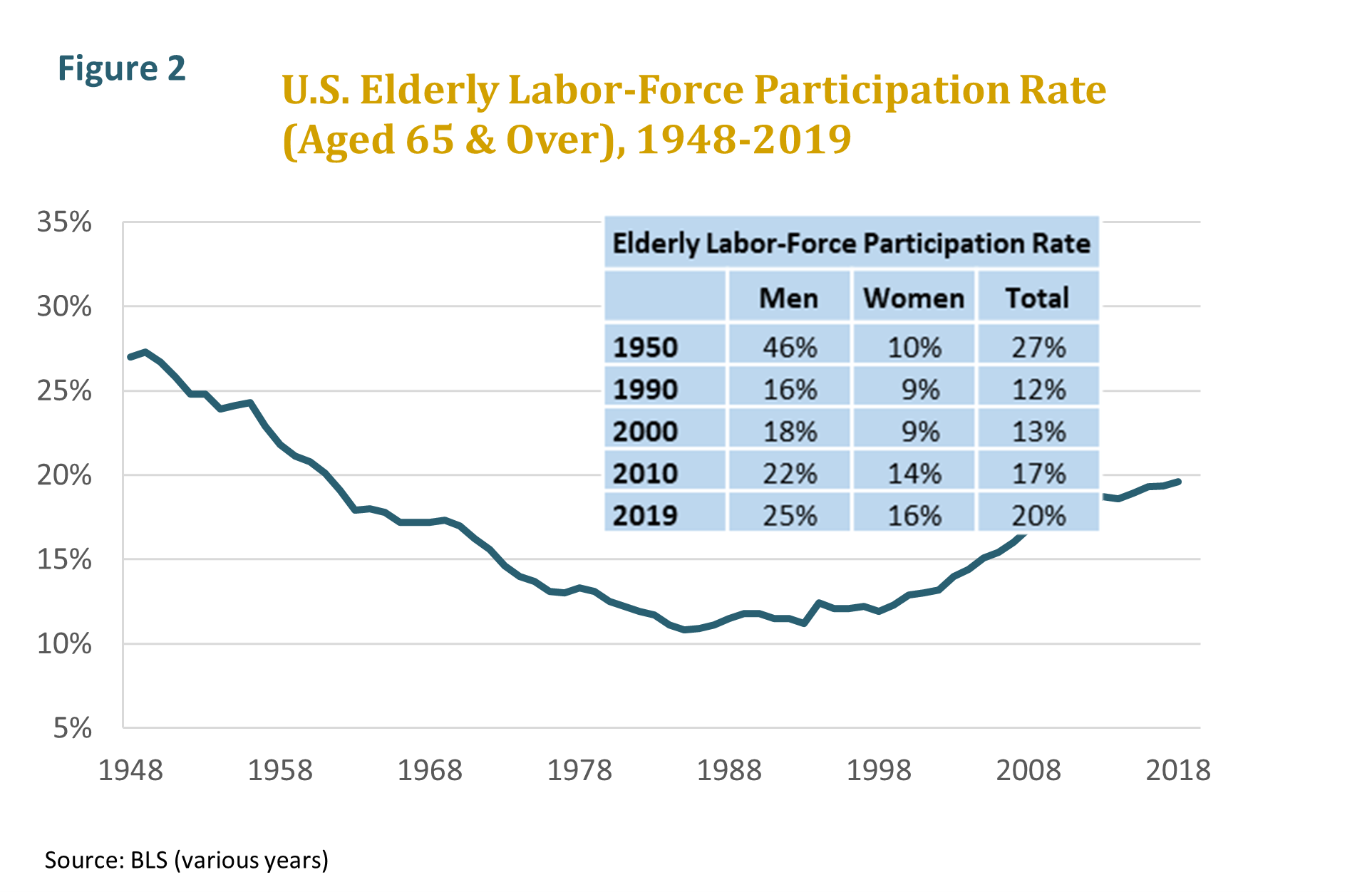

The good news is that America has already made a start at extending work lives. After falling steeply from the 1950s through the 1970s, the elderly labor-force participation rate bottomed out in the 1980s and 1990s and has since begun to rise again. (See figure 2.) Although some older workers are staying on the job longer out of financial necessity, the rebound is also being propelled by deeper economic, social, and cultural developments. These developments include the ongoing sectoral shift from manufacturing to services, better health at older ages, and a generational reevaluation of the attractions of all-or-nothing retirement versus continued productive engagement.

Government needs to do what it can to encourage this trend. Making Medicare the primary payer for most Medicare-eligible employees covered by employer health plans would remove a significant disincentive to retaining and hiring older workers. Two relatively small adjustments to Social Security could also make a large difference. The current benefit formula only counts the highest thirty-five years of wages, and thus does little or nothing to reward workers with long careers. It could be changed to include workers’ entire wage history.[3] Workers also continue to pay FICA taxes as long as they remain employed, even if they are no longer earning additional benefits. Reducing the FICA tax rate or even granting workers “paid up” status and exempting them from FICA taxes entirely once they have attained the full-benefit retirement age would encourage more of the elderly to work or, if they are already employed, to work more hours. Although this reform would naturally result in a loss in FICA revenue, some economists calculate that the additional income taxes paid on the additional employment income earned would more than compensate for the loss.[4]

Government needs to do what it can to encourage this trend. Making Medicare the primary payer for most Medicare-eligible employees covered by employer health plans would remove a significant disincentive to retaining and hiring older workers. Two relatively small adjustments to Social Security could also make a large difference. The current benefit formula only counts the highest thirty-five years of wages, and thus does little or nothing to reward workers with long careers. It could be changed to include workers’ entire wage history.[3] Workers also continue to pay FICA taxes as long as they remain employed, even if they are no longer earning additional benefits. Reducing the FICA tax rate or even granting workers “paid up” status and exempting them from FICA taxes entirely once they have attained the full-benefit retirement age would encourage more of the elderly to work or, if they are already employed, to work more hours. Although this reform would naturally result in a loss in FICA revenue, some economists calculate that the additional income taxes paid on the additional employment income earned would more than compensate for the loss.[4]

Some worry that longer work lives would be a hardship for many Americans. This is a legitimate concern. Both life expectancy and health expectancy vary greatly by income and educational attainment, and there must be policies in place that protect those workers who need to retire early. Others worry, with less justification, that more jobs for the old would mean fewer jobs for the young. The truth is that a job for one person does not deny a job to another. In fact, just the opposite is true. Additional jobs generate additional income, resulting in new demand for goods and services that in turn translates into still more jobs. While there may be competition for jobs between young and old at the firm level, or even at the industry level, at the economywide level longer work lives are a positive-sum game.

The goal is not to have everyone work forever. It is not even to have everyone work longer. But if a larger share of adults in their sixties and seventies, when the health constraints on productive aging are broadly similar to those facing adults in their forties and fifties, were to remain employed the benefits for the economy, the budget, and individuals themselves would be immense. Indeed, nothing is likely to do more to maintain economic and living standard growth in an aging America than unlocking the productive potential of the elderly, who are not only our greatest underutilized human resource, but also the fastest growing segment of the population.

Control the Growth in Health-Care Spending

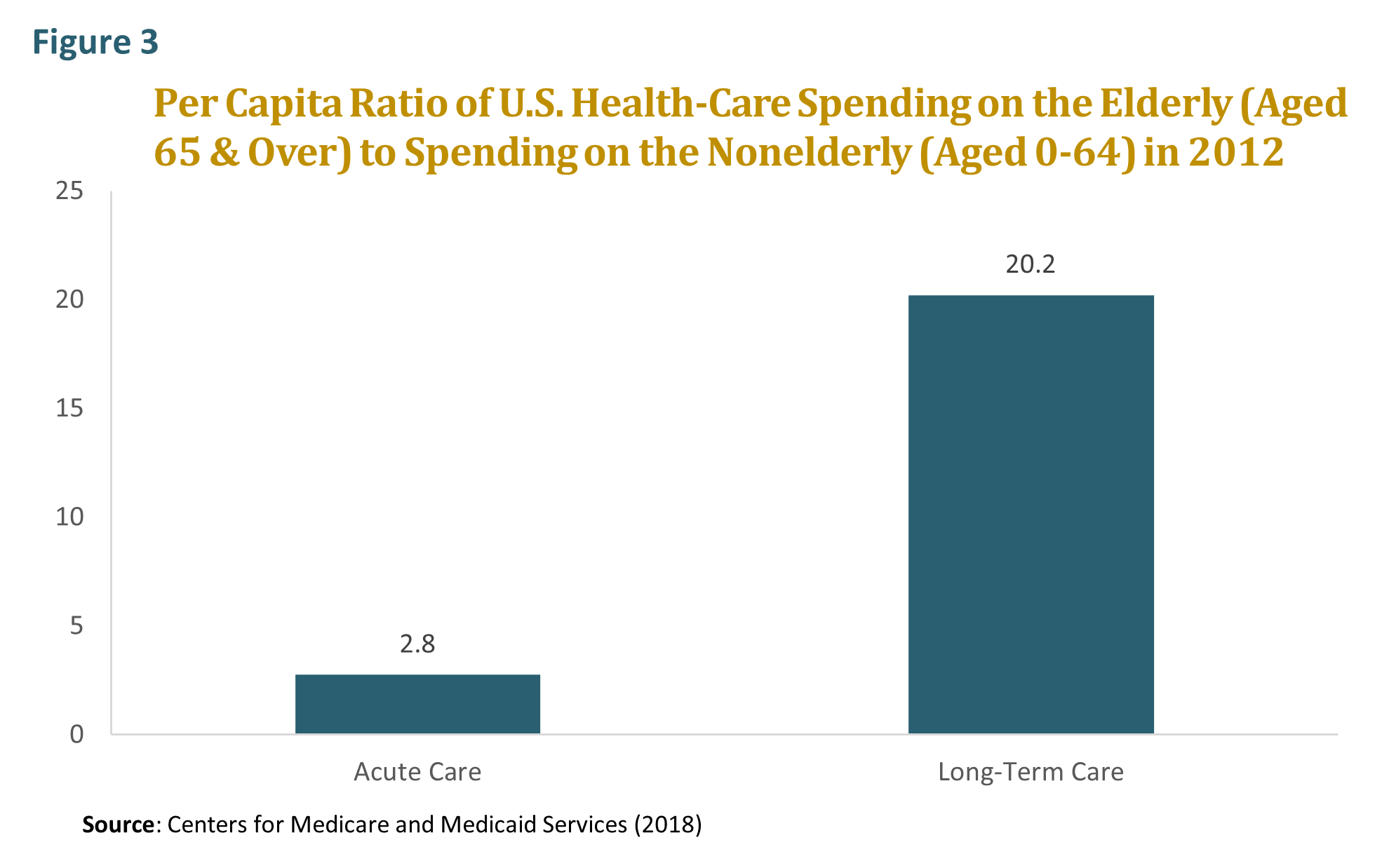

The growth in health-care spending, which has long been a burden on the budget and the economy, is about to be given a huge extra push by the aging of the population. As countries move through the “epidemiological transition,” chronic diseases replace infectious diseases as the primary cause of morbidity and mortality. Since the elderly are much more likely to suffer from chronic diseases than the nonelderly are, health-care consumption rises steeply with age. Per capita, the elderly consume roughly three times more in acute-care services than the nonelderly and roughly twenty times more in long-term care services. (See figure 3.) The elderly, moreover are the fastest growing segment of the population, the older the elderly are the more health care they consume, and the oldest elderly age groups are the fastest growing of all.

Together, these cost multipliers help to make health-care spending the most explosive dimension of old-age dependency—and the largest part of the long-term budget problem. According to the CBO, the net cost of Medicare, Medicaid, and other major federal health-benefit programs will increase by 3.9 percent of GDP between 2019 and 2050, while the cost of Social Security will increase by 1.5 percent of GDP and all other spending, except for interest on the national debt, will actually decline as a share of GDP. Nearly two-fifths of this growth is directly attributable to the increase in the number of elderly beneficiaries and the rising average age of those beneficiaries.

Together, these cost multipliers help to make health-care spending the most explosive dimension of old-age dependency—and the largest part of the long-term budget problem. According to the CBO, the net cost of Medicare, Medicaid, and other major federal health-benefit programs will increase by 3.9 percent of GDP between 2019 and 2050, while the cost of Social Security will increase by 1.5 percent of GDP and all other spending, except for interest on the national debt, will actually decline as a share of GDP. Nearly two-fifths of this growth is directly attributable to the increase in the number of elderly beneficiaries and the rising average age of those beneficiaries.

Reducing future health-care spending beneath current projections will require difficult choices. Some experts hope that improvements in the health of the elderly will lead to large cost savings, painlessly solving the problem. But as we explained in a previous issue in this series (“Are Health Spans Rising along with Life Spans?,” Fall 2020), this hope is likely to be disappointed. While it is true that rates of elderly disability, as measured by limitations on activities of daily living such as bathing or dressing, have fallen in the United States over the past few decades, the share of the elderly with expensive chronic conditions, from diabetes to hypertension and heart disease, has been flat or rising. Moreover, the obesity epidemic, along with other destructive lifestyle choices, is putting a growing share of the midlife population at risk of premature morbidity, disability, and death. If the health of midlife adults continues to deteriorate, the downward trend in elderly disability rates could stall or even reverse as younger cohorts begin to cross the threshold of old age.

Others maintain that we can achieve large cost savings simply by eliminating waste and inefficiency in our health system. There is no question that there is a vast amount of both. Thanks to pathbreaking research by scholars associated with the Dartmouth Health Atlas Project, we know that the per capita consumption of health care shows a wide variation both between and within regions that is uncorrelated with any measurable health outcome. If all providers followed the practice patterns of the most efficient providers, this research concludes that health-care spending could be reduced substantially—perhaps by as much as 30 percent.[5] We should be careful, however, not to exaggerate how easy this savings will be to achieve. In practice, identifying pure waste is difficult. Demonstrating statistically that certain higher-cost tests and treatments are ineffective does not mean that they are ineffective in every case. While systematic adherence to best practice guidelines would eliminate much wasteful spending, it would also eliminate some beneficial spending, which is another way of saying that it would entail real cost-benefit trade-offs. Without dramatic changes in the U.S. health system’s cost-plus incentives, from open-ended tax subsidies to fee-for-service payment, it is doubtful that patients and providers will be willing to make such trade-offs.

Even if we could identify and eliminate all of the waste, moreover, it would constitute a one-time savings that does little to alter the long-term growth in health-care spending. In addition to population aging, this growth is driven by the ongoing advances in medical testing, screening, diagnostics, pharmaceuticals, and surgery that are pushing up the cost of the research, technology, and skilled labor underlying every medical visit. It is also driven by the steady rise in the standard of “health” that Americans expect their doctors and hospitals to deliver. Good health, after all, is not a fixed goal. It is a subjective standard that rises over time as societies become more affluent, less tolerant of bad health or risk, and more secular—that is, more apt to see happiness in the here and now as life’s ultimate goal. As this expanding concept of health interacts with medical advances, it is transforming the practice of medicine. While once it meant an occasional visit to the doctor or hospital, it is fast becoming a lifelong process of diagnostics and fine-tuning in which any extra dollar spent is likely to confer some perceived benefit.

None of this is to say that the growth in health-care spending cannot be controlled. Other developed countries spend much less per capita on health care than the United States does while achieving better health outcomes, at least as measured by life expectancy at birth. Many factors have contributed to more rapid U.S. cost growth, including higher U.S. administrative costs, the greater fragmentation of the payer side of the U.S. market, and the worse health profile of the U.S. population. The most critical factor, however, has been the lack of any effective budget constraint designed to encourage cost-benefit trade-offs at either the macro or clinical level. Most developed countries set overall budgets for government health-care spending and enforce those budgets through some combination of controls on the price or the volume of health-care services. The United States does not.

Too often in the health-care debate, both policymakers and policy experts have insisted on pretending that cost-benefit trade-offs are unnecessary. It is time we acknowledged that they are essential. Effective cost control will require some people to give up some care that is potentially beneficial—what Brookings economist Henry Aaron has called the “painful prescription.”[6] Once this is acknowledged we can begin to engage the real debate, which is about how best to set limits. Should it be through top-down government regulation? Or should it be through some sort of capitated prepayment or “premium support” that realigns patient and provider incentives? Whatever the answer, the longer we wait to decide the more difficult the choices will become.

Stabilize the National Debt as a Share of GDP

Deficit hawks have always acknowledged that there are legitimate and sometimes compelling reasons for the federal government to borrow. It makes sense for the government to borrow to finance investments likely to yield long-term returns, in much the same way that it makes sense for private businesses to do so. It also makes sense for it to borrow during economic downturns in order to finance stimulus spending and prop up aggregate demand. And it certainly makes sense for it to borrow as necessary during national emergencies. War is the most obvious example, but a global pandemic certainly qualifies.

Deficit hawks have also cautioned, however, that deficit spending is not costless and that a large and growing national debt poses serious dangers. Government borrowing can siphon national savings away from potentially more productive private-sector investments, undermining long-term economic growth. Interest payments on the national debt can crowd spending on other priorities out of government budgets. If the demands of government borrowing on capital markets become too great, it can trigger a spike in interest rates, further pushing up debt service costs. And if capital markets come to suspect that government may no longer be able to service the debt, it can trigger a financial crisis. One way or the other, it will be future generations of workers and taxpayers who bear the cost in diminished living standards.

An increasingly influential school of thought known as modern monetary theory argues that these constraints on borrowing have always been greatly exaggerated, and in any case do not apply today.[7] With private investment demand anemic and the world awash in excess savings, there is no credible reason to believe that government borrowing is crowding out private-sector investment. With interest rates at record lows, there is also no real danger of budgetary crowding out, spiraling borrowing costs, or a crisis of confidence in capital markets. According to the modern monetary theorists, government borrowing has in effect become costless. Not only is it safe for the federal government to run large structural budget deficits, it would be economic folly for it not to run them.

All of this may be true, but only in the near term. When it comes to the long term, the modern monetary theorists are asking America to make a reckless gamble. Their argument is premised on the assumption that interest rates will remain low indefinitely. There are good reasons to be skeptical that this will be the case, including some demographic ones. Up to now, population aging has depressed investment demand more than savings supply, pulling down interest rates, but in the future it could push them up again as a much larger share of the population enters the low-saving retirement years. Even if interest rates remain at or near historical lows, moreover, so may real GDP growth. When real GDP is growing rapidly, it is possible for government to run large annual deficits and still have a stable or even declining debt-to-GDP ratio, since the debt is denominated in nominal dollars. When real GDP growth slows, the same annual deficits may mean a rapidly rising debt-to-GDP ratio.

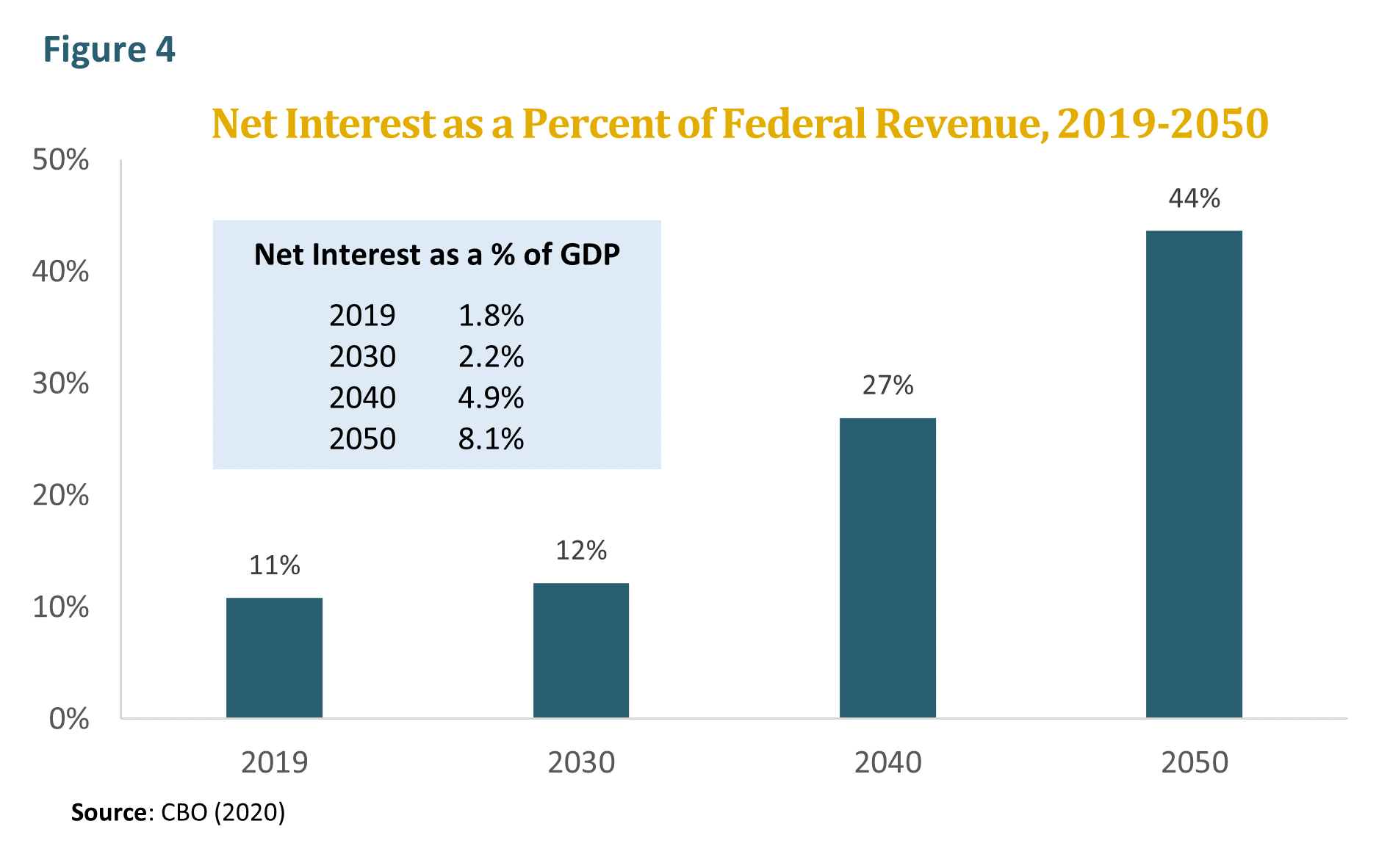

The debt held by the public has already reached 100 percent of GDP, up from 35 percent in 2007 on the eve of the Great Recession. According to the latest CBO long-term budget projections, which of course do not take into account the new round of stimulus spending that will soon be enacted, it is due to climb to 195 percent of GDP by 2050. Will this be financeable? Maybe, if real interest rates top out at 2.5 percent, which is what CBO assumes—though even then net interest payments would by 2050 be consuming over two-fifths of total federal revenue. (See figure 4.) But what if interest rates rise further? Or what if the global financial system of 2050 is structured differently from today’s? America’s ability to borrow without seeming limit depends not only on low interest rates, but also on the status of the dollar as global reserve currency. Thirty years is a long time, especially in an era when the global economic and geopolitical landscape is shifting so rapidly. Do we really want to bet our children’s and grandchildren’s future on the assumption that the dollar will still enjoy the same privileged status in 2050?

Over the next few decades, the federal budget will come under intense pressure from rising retirement and health-care spending. Ideally, America would be approaching this fiscal gauntlet with the national debt low and falling as a share of GDP. Instead, it is at a postwar high and rising. If history teaches just two things about government debt and financial markets, they are, first, that there exists some debt-to-GDP ratio at which, once reached, perceived credit risk will rise and new debt will no longer be financeable at tolerable interest rates, and second, that we cannot know in advance exactly what that ratio is. The usual economic constraints on deficit spending may have been suspended for a while, but they have not been repealed. America’s leaders urgently need to develop a long-term budget strategy that stabilizes the national debt. If they delay much longer, it may be too late.

Over the next few decades, the federal budget will come under intense pressure from rising retirement and health-care spending. Ideally, America would be approaching this fiscal gauntlet with the national debt low and falling as a share of GDP. Instead, it is at a postwar high and rising. If history teaches just two things about government debt and financial markets, they are, first, that there exists some debt-to-GDP ratio at which, once reached, perceived credit risk will rise and new debt will no longer be financeable at tolerable interest rates, and second, that we cannot know in advance exactly what that ratio is. The usual economic constraints on deficit spending may have been suspended for a while, but they have not been repealed. America’s leaders urgently need to develop a long-term budget strategy that stabilizes the national debt. If they delay much longer, it may be too late.

Resist Protectionism

Global aging is a global challenge requiring global solutions. As the term correctly implies, nearly every country in the world is projected to experience at least some shift toward slower population growth and an older age structure. This does not mean, however, that the world is demographically converging. Most of today’s youngest countries are projected to experience the least aging, while most of today’s oldest countries are projected to experience the most aging. As a result, the world will see an increasing divergence, or “spread,” of demographic outcomes over the next few decades. At the same time, it is likely to see an increasing divergence in economic outcomes.

This in turn suggests that globalization will have an ever more critical role to play in ensuring America’s prosperity. An aging country with a closed economy cannot escape the tyranny of its own demography. Open global capital markets, however, can match savers in aging and slowly growing countries with investment opportunities in younger and faster-growing ones. Open global labor markets can similarly match workers with job opportunities, whether through outsourcing or immigration.

The danger is that an aging America will be tempted to roll back globalization. With domestic markets growing more slowing or even contracting, businesses and unions may lobby for anticompetitive changes in the economy. We may see growing cartel behavior to protect market share and more restrictive rules on hiring and firing to protect jobs. We may also see increasing pressure on government to block foreign competition. Historically, eras of stagnant population and market growth—think of the 1930s—have been characterized by rising tariff barriers, autarky, corporatism, and other anticompetitive policies that tend to shut the door on free trade and restrict the movement of capital and labor.

The recent rise of protectionist sentiment in the United States and many other developed countries obviously has varied and complex causes. But there is little question that the demographically led slowdown in economic growth has been a prime driver. America’s leaders need to resist protectionism’s temptations. If history repeats itself and the United States turns inward, it will compound the negative effects of population aging. Our nation, along with the rest of the world, will be both poorer and less stable.

A QUARTERLY SERIES

The Shape of Things to Come

Over the next few decades, the aging of America promises to have a profound effect on the size and shape of our government, the dynamism of our economy, and even our place in the world order. The Concord Coalition and author Richard Jackson of the Global Aging Institute (GAI) have joined forces to produce a quarterly issue brief series that explores the fiscal, economic, social, and geopolitical implications of the aging of America. Although the series is U.S. focused, it also touches on the aging challenge in countries around the world and draws lessons from their experience. Concord and GAI hope that it will inform the debate over the aging of America and help to push it in a constructive direction.

About the Global Aging Institute

The Global Aging Institute (GAI) is a nonprofit research and educational organization dedicated to improving our understanding of global aging, to informing policymakers and the public about the challenges it poses, and to encouraging timely and constructive reform. GAI’s agenda is broad, encompassing everything from retirement security to national security, and its horizons are global, extending to aging societies worldwide.

GAI was founded in 2014 and is headquartered in Alexandria, Virginia. Although GAI is relatively new, its mission is not. Before launching the institute, Richard Jackson, GAI’s president, directed a research program on global aging at the Center for Strategic and International Studies which, over a span of fifteen years, played a leading role in shaping the debate over what promises to be one of the defining challenges of the twenty-first century. GAI’s Board of Directors is chaired by Thomas S. Terry, who is CEO of the Terry Group and past president of the International Actuarial Association and the American Academy of Actuaries. To learn more about GAI, visit us at www.GlobalAgingInstitute.org.

About The Concord Coalition

The Concord Coalition is a nationwide, non-partisan, grassroots organization advocating generationally responsible fiscal policy. It was founded in 1992 by former Senator Paul E. Tsongas (D-Mass.), former Senator Warren B. Rudman (R-N.H.), and former U.S. Secretary of Commerce Peter G. Peterson with a non-partisan mission to confront the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges and build a sound economy for future generations. The Concord Coalition’s national field staff, policy staff, and volunteers carry out the organization’s public education mission throughout the nation.

[1] Nicholas Eberstadt, “Demographic Exceptionalism in the United States: Tendencies and Implications,” Agir 29 (January 2007).

[2] See, among others, Robert N. Butler, The Longevity Revolution: The Benefits and Challenges of Living a Long Life (New York: Public Affairs, 2008), 237-55; Chenkai Wu et al., “Association of Retirement Age with Mortality: A Population-Based Longitudinal Study among Older Adults in the USA,” Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health 70, no. 9 (March 2016); and Ursula M. Staudinger et al., “A Global View on the Effects of Work on Health in Later Life,” The Gerontologist 56, issue supplement 2 (April 2016).

[3] For a thoughtful proposal that addresses how this could be done, see Marc Goldwein, Maya MacGuineas, and Chris Towner, Promoting Economic Growth through Social Security Reform (Washington, DC: Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget, 2019).

[4] See Robert L. Clark and John B. Shoven, Enhancing Work Incentives for Older Workers: Social Security and Medicare Proposals to Reduce Work Disincentives (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution, January 2019).

[5] The Dartmouth Health Atlas Project has been publishing research on medical practice variation in the United States since 1996. See https://www.dartmouthatlas.org/.

[6] Henry J Aaron and William B. Schwartz, The Painful Prescription: Rationing Hospital Care (Washington, DC: The Brookings Institution, 1984).

[7] For an exposition of modern monetary theory by one of its leading proponents, see Stephanie Kelton, The Deficit Myth: Modern Monetary Theory and the Birth of the People’s Economy (New York: Public Affairs Books, 2020).

Continue Reading