Introduction

The Constitution (Article I, section 9, clause 7) gives Congress the “power of the purse,” which means no money can be paid out of the Treasury unless it has been appropriated by an act of Congress. However, President Biden recently announced a series of changes to the federal student loan program that could potentially cost $1 trillion.[1]

Critics claim these changes exceed statutory authority and are contrary to congressional intent, while supporters claim they are within the scope of executive authority. These opposing views highlight the longstanding dispute between the legislative and executive branches of government over the power to increase spending. This dispute also reveals how the Biden Administration’s interpretation of the unique budgetary treatment of the student loan program would tip the balance of power in the President’s favor.

This issue brief will review how student loans are reported in the federal budget, examine the Department of Education’s authority to change the student loan program, and consider how these two factors may result in a major expansion of the President’s power to unilaterally and substantially increase the national debt.

Federal Credit Reform Act

The President’s authority to modify the student loan program and whether those modifications will result in the expenditure of funds, and thus exceed his authority, depends on the extent of the modifications, as well as the definition of “appropriations.” To evaluate the legal arguments presented below, it’s necessary to understand the budgetary treatment of federal loan programs.

The federal government provides direct loans and loan guarantees to individuals and businesses who borrow money from the government or private lenders. Prior to the enactment of the Federal Credit Reform Act (FCRA), the cost of these loans were reported on an annual cash-flow basis.[2]

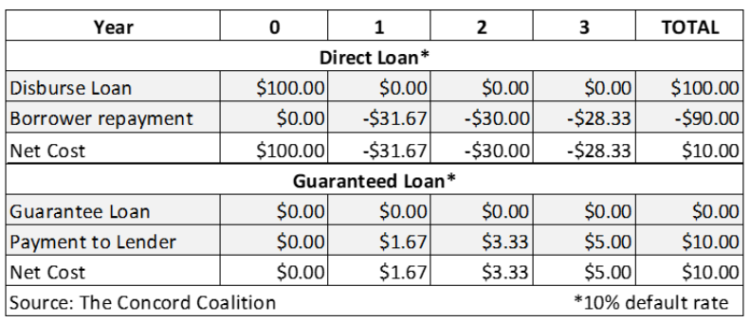

That means when the government made a direct loan, the amount borrowed was reported in the budget as an outlay in the year the loan was made; and when the borrower repaid the loan, the payment was reported as an offsetting receipt in the year it was received. When the government guaranteed a loan made by a private lender, there was no outlay reported in the budget unless the borrower defaulted in a subsequent year.[3]

Figure 1 shows an example of how the budget would report the annual cash-flows for a direct loan and a guaranteed loan, assuming a three-year repayment period with zero interest and a 10 percent default rate. Administrative costs are excluded from these calculations.

Figure 1: Outlays and Offsetting Receipts Under Cash-Flow Reporting (Before FCRA)

Critics complained cash-flow reporting gave Congress an incentive to expand guaranteed loans, rather than direct loans, because they appeared to cost less – at least in the short-run. The goal of the FCRA was to report both types of loans on a comparable basis. Thus, rather than reporting the annual cash-flows, the budget now reports the net present value of expected future cash-flows.

Under the FCRA, both loans in Figure 1 would be reported with a cost of $10 in the initial year and $0 in subsequent years. The cost of the loan divided by the amount of the loan is the subsidy rate, which in this example is 10 percent ($10 / $100). The subsidy rate is one way to measure the extent to which the government subsidizes the borrower. The subsidy rate can also be negative when the interest rate on the loan exceeds the interest rate on the government securities used to calculate the present values, and the default rate is sufficiently low. A negative subsidy rate means the borrower pays more than the present value of the loan. (See Appendix) However, the subsidy rate excludes administrative costs, so it does not fully reflect the loss or gain to the government or the borrower.

The net present value reported in the federal budget in the initial year of the loan is an estimate. In the case of student loans, the Department of Education makes assumptions about interest rates, deferral rates, forbearance rates, default rates, the borrower’s income and choice of repayment plan, and participation in a loan forgiveness plan. Net present value estimates are prepared for each group of students (or cohort) who take out loans each year; and estimates for previous cohorts are revised each year based on changes in data and assumptions, as well as legislative, regulatory, and policy changes.

According to a recent report, the portfolio of direct student loans issued over the past 25 years (1997-2021) was originally estimated to collect $114 billion more than the amount of loans (i.e., negative subsidy rate); but the portfolio is now estimated to collect $197 billion less than the amount of loans (i.e., positive subsidy rate).[4] The $311 billion shift from lower to higher deficits is the result of changes in economic and technical assumptions, legislation, and administrative actions. Ironically, the proposal to replace guaranteed loans with direct loans was included in the Affordable Care Act based on the assumption that it would save $61 billion and help pay for the legislation, a result that now seems highly unlikely.[5]

Unlike legislative changes that are subject to statutory “pay-as-you-go” provisions, which require spending increases be offset by spending decreases or revenue increases, administrative actions that increase entitlement spending are not subject to any offsets.[6] Under the FCRA, administrative modifications of mandatory loan programs are automatically funded as new entitlement spending.

In 2005, the Office of Management and Budget (OMB) issued a memorandum “implementing a budget-neutrality requirement on agency administrative actions affecting mandatory-spending programs.”[7] Essentially, OMB requested that any agency proposing to increase spending through administrative actions also propose corresponding decreases. However, this administrative pay-go policy was not legally binding on subsequent administrations.

Thus, if the latest student loan changes announced by the President are implemented, the additional costs will be included in the next annual budget without any offsets.[8] As explained by the Congressional Budget Office (CBO) in its August Monthly Budget Review:[9]

“This year, both the timing and the amounts of the changes to the student loan program are uncertain. Without the changes to student loans, CBO’s projection of the 2022 budget deficit would be about $1.0 trillion, compared with a $2.8 trillion shortfall last year. If significant numbers of student loans are modified in September, the 2022 deficit could be considerably larger than CBO has estimated. Some of the announced changes (such as the changes to income-driven repayment plans) will increase deficits in future years.”

The goal of the FCRA is to treat the cost of federal loan programs similar to the cost of other federal programs. As mandatory entitlements, student loans are funded with automatic appropriations as needed to provide credit to eligible students. Modifications of these loans result in additional appropriations based on the net present value of the modifications. However, establishing the connection between modifications and appropriations only resolves that issue. It does not resolve whether the Department of Education has the authority to make such modifications.

Major Questions Doctrine

When Congress enacts legislation, it often uses vague or ambiguous statutory language. When someone challenges an action taken by a federal agency based on such language, the federal courts have generally deferred to the agency’s interpretation of the applicable statute. However, the courts have also determined in cases of vast economic and political significance, an agency’s actions must be supported by clear congressional authorization.[10]

President Biden recently announced the Department of Education would cancel $10,000 to $20,000 in student loans for 43 million current and former college students.[11] Estimates suggest this level of debt forgiveness could cost the federal government over $500 billion, an amount that clearly rises to the level of national significance.

According to the Department of Education and the Department of Justice, this debt relief is being granted under the Higher Education Relief Opportunities for Students (‘‘HEROES’’) Act of 2003.[12] The relevant section of this Act states in part:[13]

(1) Notwithstanding any other provision of law… the Secretary of Education… may waive or modify any statutory or regulatory provision applicable to the student financial assistance programs… as the Secretary deems necessary in connection with a… national emergency to provide the waivers or modifications authorized by paragraph (2).

(2) The Secretary is authorized to waive or modify any provision described in paragraph (1) as may be necessary to ensure that—

(A) …affected individuals are not placed in a worse position financially in relation to that financial assistance because of their status as affected individuals…

The statute defines an affected individual in part as someone who “resides or is employed in an area that is declared a disaster area by any Federal, State, or local official in connection with a national emergency.” The national emergency declaration with respect to the COVID-19 pandemic (and the subsequent extensions) would make every student loan recipient in the country an affected individual.[14]

The Administration relies on paragraph (1) to claim they have the authority to waive or modify any provision of the student loan program, therefore canceling student debt is within their legal authority. However, paragraph (1) is limited by paragraph (2). The Administration claims canceling student debt is permissible under subparagraph (2)(A) because it would ensure individuals are not placed in a worse financial position with respect to their student loans due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

However, this conclusion is contrary to the rules of statutory construction that dictate words should be interpreted according to their plain meaning. To prevent someone from being worse off does not mean to make them better off. Canceling student loans that existed prior to the emergency would place students in a better financial position than they were before the emergency.

The provisions of Paragraph (2) are limited to changes intended to address circumstances that occur during an emergency. For example, (2)(D) would allow students who are forced to withdraw from college due to COVID to avoid repaying the portion of a loan awarded for the semester they did not attend. Moreover, changes authorized in (2)(B) are not only intended to ease the burden on students, but also protect the financial integrity of the student loan program. A categorical waiver of debt incurred prior to the emergency does not meet that requirement.

In addition to debt cancellation, the Department of Education also plans to introduce a new income-related repayment plan that would cap monthly undergraduate loan payments at five percent of the portion of a borrower’s income that exceeds 225 percent of the federal poverty level; forgive unpaid interest; and forgive loans under $12,000 after 10 years.[15] Estimates suggest this change could potentially cost an additional $450 billion.[16]

The Secretary of Education has some authority to modify income-related repayment plans through the regulatory process. But given the potential cost of the proposed changes, this authority would also be subject to judicial review under the major questions doctrine.

Income-related plans (also called “income-based,” “income-contingent,” or “income-driven”) were enacted as part of a major expansion of the direct lending program included in the Omnibus Budget Reconciliation Act of 1993.[17] The original statutory language gave the Secretary of Education considerable discretion to determine the details of the income-related plan, subject to the requirement that the repayment period was “not to exceed 25 years.”

This language might appear to establish an upper limit, while providing the flexibility to select a shorter period. However, congressional hearings indicate that 25 years was both a ceiling and a floor, with the dual purpose of collecting smaller payments over a longer period while avoiding a lifetime of payments. As the Deputy Secretary of Education testified:[18]

“As to what the cost of that would be, we see it as a wash. You would have some increased costs, obviously, in stretching out the loan and servicing that loan and all the administrative needs that go with that, but you would also have some savings in that you would eventually get paid, and even if you get paid $10 a week, it’s better than getting paid nothing. So that is an advantage. And two, there would be interest charged on that, so it isn’t like you are getting a free ride. The hard part is when do you cut it off. Do you say you are going to go to your grave owing your student loan after 40 years. So there is a provision in the bill that says the Secretary will make some designation as to when you call it quits and you are forgiven. One possibility is around 25 years or so.”

The congressional intent to ease the burden of debt by lowering monthly payments while maintaining the financial integrity of the student loan program is also evident in the statutory language that allows the Secretary to provide “on a case-by-case basis, an alternative repayment plan to a borrower [with] …exceptional circumstances… [provided that] the Secretary shall ensure that such plans do not exceed the cost to the Federal Government, as determined on the basis of the present value of future payments by such borrowers, of loans made using the [other] plans available…” to other borrowers under the student loan program.[19]

The original statutory language allowed the Secretary to determine how much student loan payments could vary with respect to income. However, subsequent statutory changes limited payments to 15 percent of the borrower’s income that exceeded 150 percent of the federal poverty level.[20] Congress subsequently reduced the repayment rate to 10 percent and reduced the repayment period to 20 years.[21] In both instances, Congress included these changes with an expansion of direct lending that was intended to reduce the overall cost of the student loan program.

The Department of Education’s plan to use its regulatory authority to reduce the repayment rate to 5 percent, increase the income threshold to 225 percent of poverty, and forgive loans under $12,000 after 10 years would ignore the statutory thresholds and contradict congressional intent with respect to maintaining the financial integrity of the student loan program. But someone must have legal standing to challenge these administrative modifications in federal court.

Judicial Review

The Constitution (Article III, Section 2) gives federal courts the authority to adjudicate cases and controversies. To challenge an agency’s action in court, the plaintiff must generally have “standing,” which means they suffered an actual or imminent concrete and particularized injury from the action that can be redressed by a favorable court decision.[22]

The Department of Education’s actions to cancel student debt creates several potential plaintiffs. All newly issued student loans are now direct loans; however, there is over $200 billion in guaranteed loans that have not been repaid.[23] To the extent these guaranteed loans are held by non-federal entities, they would be adversely affected by debt cancellation unless they are provided reimbursement.[24]

Even if the debt cancellation were limited to direct loans, Congress could assert its legal standing to sue under the appropriations clause of the Constitution.[25] Only Congress has the authority to appropriate money from the U.S. Treasury. The Justice Department claims that loan forgiveness merely prevents the government from collecting money, rather than spending money. But this distinction is not relevant under the FCRA. The purpose of the FCRA was to “place the cost of credit programs on a budgetary basis equivalent to other Federal spending.”[26]

The disbursement of loans (i.e., outlays) and the repayment of loans (i.e., offsetting receipts) are no longer considered two separate transactions. Any modification of the direct student loan program that increases the “cost,” as determined by the change in net present value, results in a corresponding appropriation under the terms of the FCRA.[27] Because administrative modifications will result in an appropriation, the legal question becomes whether those modifications comply with statutory requirements and are consistent with congressional intent.

Whether Congress chooses to challenge the Department of Education’s actions will likely depend on the results of the next election. If the Democrats maintain their majorities in both the House and the Senate, a legal challenge seems highly unlikely. If the Republicans retake the majority, it seems more likely.

Conclusion

College graduates typically earn significantly more income throughout their lifetime than non-graduates.[28] The argument for financing their education with student loans is that the additional income will allow them to repay their debts. However, not every student earns more, and some fail to graduate, so the cost of a traditional 10-year fixed repayment plan is not always affordable.

To address this concern, Congress and the Department of Education have expanded income-related repayment plans and loan forgiveness programs through legislation and regulation.[29] These plans limit payments based on the borrower’s income and write-off any remaining balance after 20 or 25 years of payments, or even 5 or 10 years if the borrower accepts certain public service jobs.[30]

But rather than balancing the desire to help students repay their loans with the need to protect the financial integrity of the student loan program, the President’s debt forgiveness plan focuses on reducing the number of students who must ever repay their loans. Although the legal authority to implement this plan through administrative actions is highly questionable, it’s unclear whether anyone will successfully challenge these actions. The result may be another substantial increase in the national debt.

* * *

Appendix – Hypothetical Student Loan Calculations

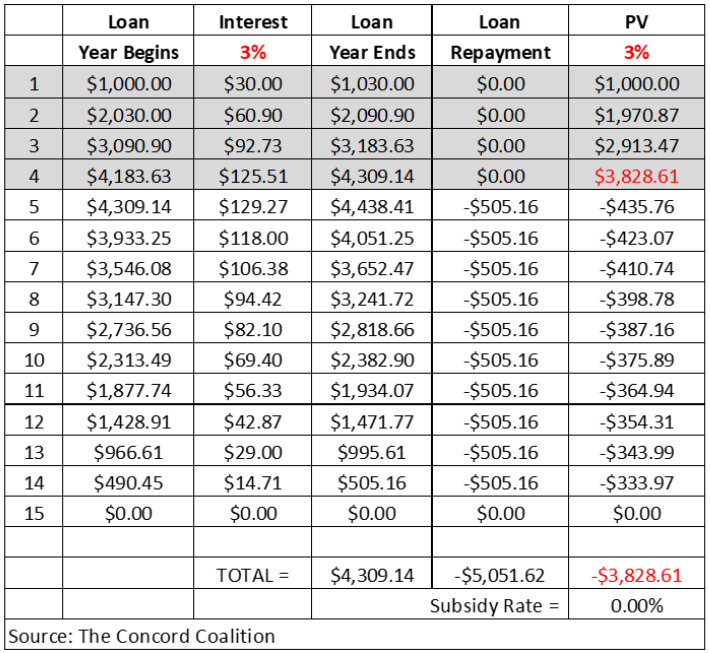

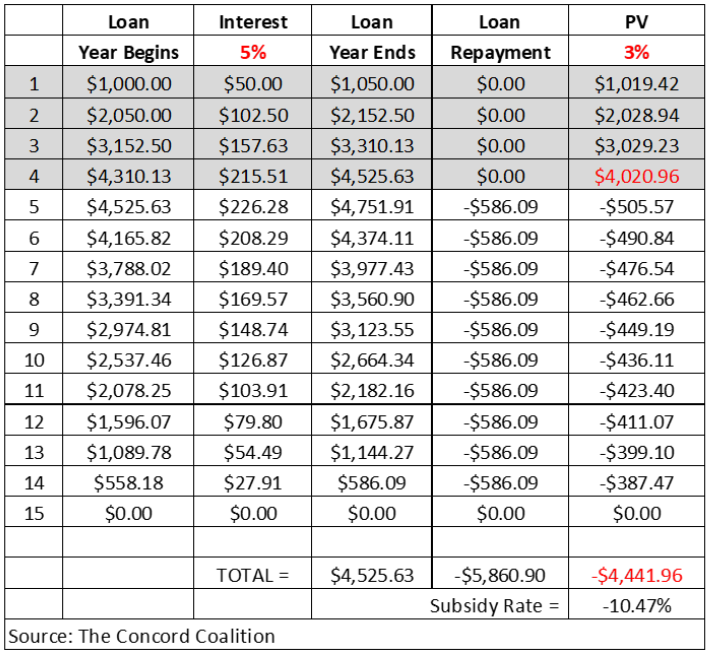

The figures below show the net present values for two hypothetical student loans. Both figures assume the student borrows $1,000 a year for four years and then repays the loan over ten years. Interest accrues until the student graduates and payments begin at the end of the first year following graduation.

Figure A-1 assumes the interest rate paid by the student and the interest rate on the government securities used to calculate the present values are the same (3%). Assuming all payments are made in full and on time, the present value of the loan is equal to the present value of the payments, thus the net present value is $0.

Figure A-1: Hypothetical Student Loan with Equal Interest Rates

The calculations in Figure A-2 are identical except the interest rate paid by the student is assumed to be two percentage points higher than the interest rate on the government securities (5% vs 3%). As a result, the present value of the loan is less than the present value of the payments, thus the net present value is -$421 ($4,020.96 – $4,441.96), which represents a negative subsidy rate of roughly 10 percent. When the government charges an interest rate higher than its own borrowing rate, the additional interest income is available to offset a portion of the losses resulting from student loan defaults.

Figure A-2: Hypothetical Student Loan with Unequal Interest Rates

[1] The Biden Student Loan Forgiveness Plan: Budgetary Costs and Distributional Impact (upenn.edu)

[2] Public Law 101-508, STATUTE-104-Pg1388.pdf (congress.gov)

[3] Federal Student Loan Programs Data Book In the case of student loans, federal outlays to private lenders include interest benefits, special allowances, death and disability claims, bankruptcy claims, and reinsurance default claims paid to guaranty agencies.

[5] H.R. 4872, Reconciliation Act of 2010 (Final Health Care Legislation) | (cbo.gov)

[7] OMB Controls on Agency Mandatory Spending Programs: “Administrative PAYGO”

[8] Letter on regs (cbo.gov) Once these revisions are incorporated into the updated budget baseline, Congress could pass legislation to cancel the changes before they take effect and use the “savings” to pay for other entitlement spending.

[9] Monthly Budget Review: August 2022 | (cbo.gov)

[11] FACT SHEET: President Biden Announces Student Loan Relief for Borrowers Who Need It Most

[12] 2022-18731.pdf (govinfo.gov); download (justice.gov)

[13] 20 U.S. Code § 1098bb – Waiver Authority | (cornell.edu)

[14] COVID-19 Emergency Declaration | FEMA.gov

[15] The Biden-Harris Administration’s Student Debt Relief Plan Explained (studentaid.gov)

[16] The Biden Student Loan Forgiveness Plan: Budgetary Costs and Distributional Impact (upenn.edu)

[17] Public Law 103-66, STATUTE107.pdf (congress.gov)

[19] 20 U.S. Code § 1087e – Terms and conditions of loans | (cornell.edu)

[20] Public Law 110-84, PUBL084.110 (congress.gov)

[21] Public Law 111-152, PUBL152.PS (congress.gov)

[22] An Introduction to Judicial Review of Federal Agency Action (congress.gov)

[23] Federal Student Loan Portfolio | Federal Student Aid

[24] Federal Family Education Loan Program Lender and Guaranty Agency Reports | Federal Student Aid Student loans are guaranteed by state or private non-profit guaranty agencies which are reinsured by the federal government. Student loan forgiveness without appropriate reimbursement would adversely affect private lenders including universities, private investors like Sallie Mae, collection agencies, and guaranty agencies.

[25] US House vs Burwell (uscourts.gov)

[26] 2 U.S. Code § 661 – Purposes | (cornell.edu)

[27] 2 U.S. Code § 661a – Definitions | (cornell.edu); 2 U.S. Code § 661c – Budgetary treatment | (cornell.edu); 20 U.S. Code § 1087a – Program authority | (cornell.edu)

[28] Do the Benefits of College Still Outweigh the Costs? (newyorkfed.org)

[29] The Cost of the Federal Student Loan Programs and Repayment Plans | (cbo.gov)

[30] Federal Student Loan Forgiveness and Loan Repayment Programs (congress.gov)

Continue Reading