Social Security is the largest program in the federal budget. It provides monthly income to over 60 million Americans — most of whom depend on it as their largest source of retirement income. That spending is financed by a tax on worker wages. As the population ages, more people will become eligible for Social Security relative to the workers left in the workforce paying taxes.

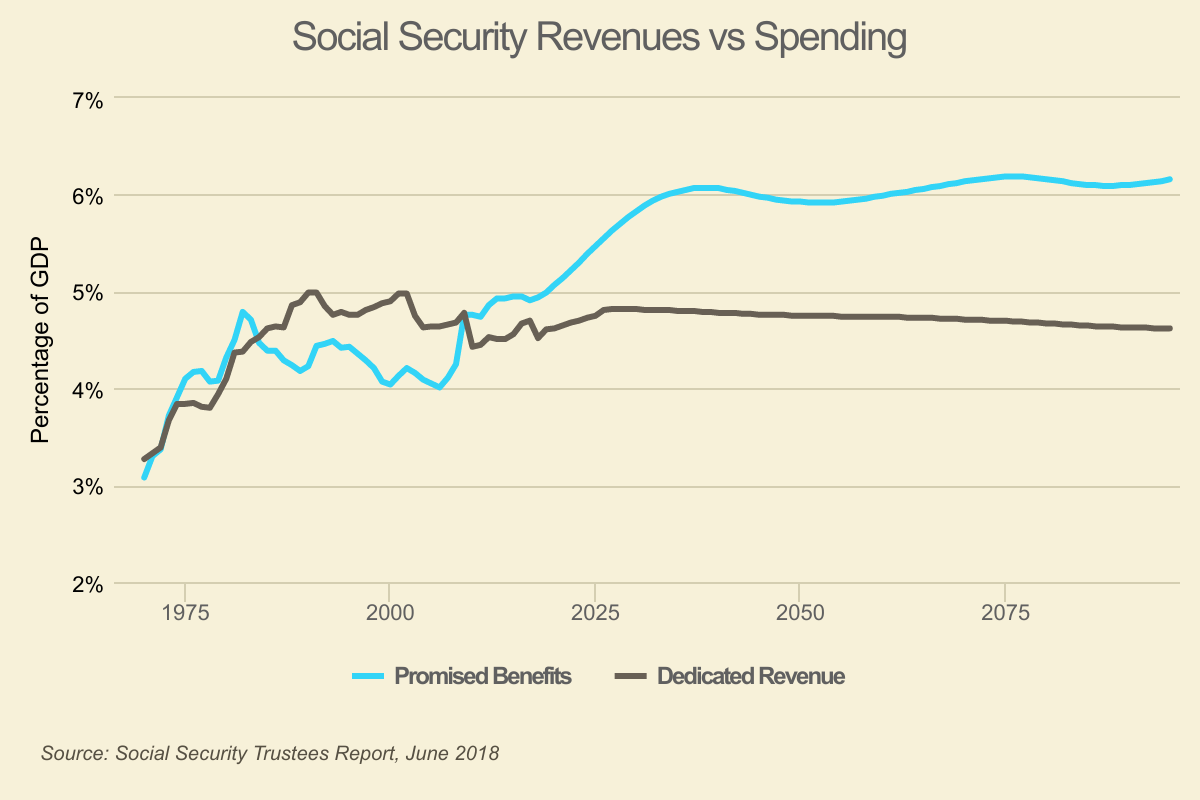

That leads to a gap between revenues and spending that is a major contributor to the nation’s unsustainable long-term fiscal challenge.

What is Social Security?

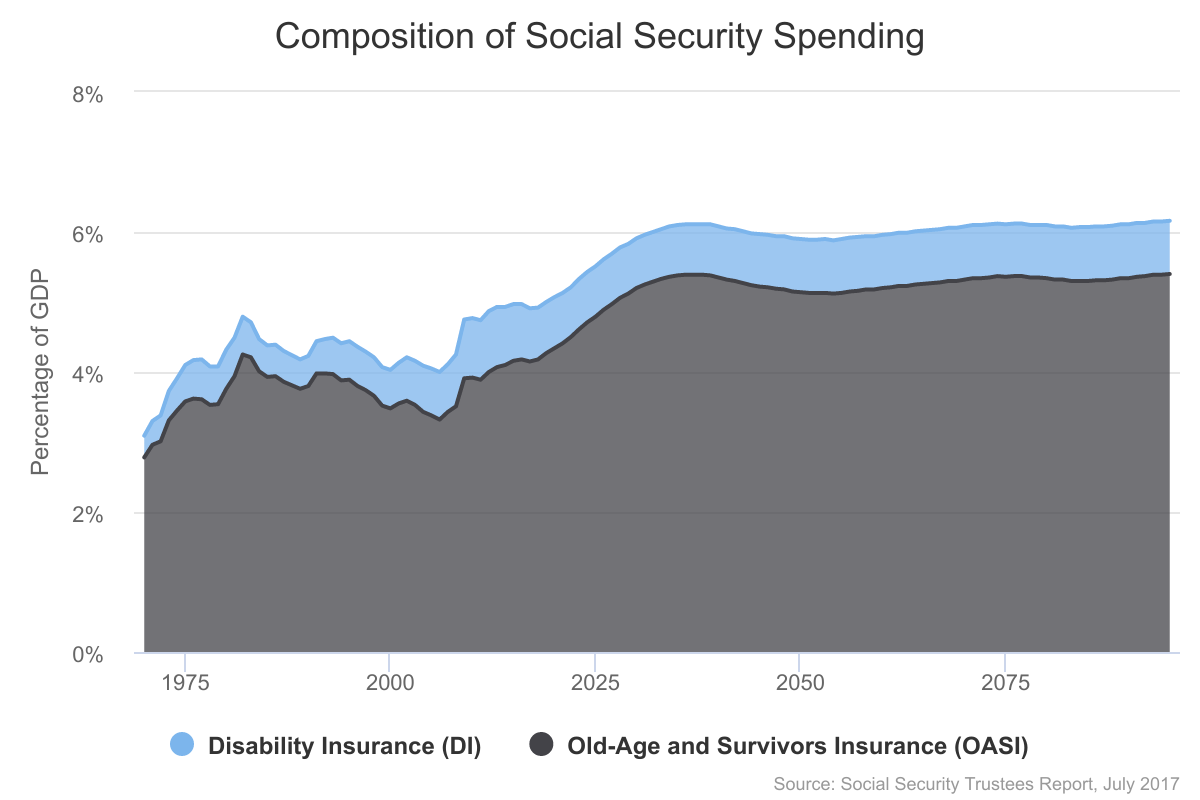

Social Security actually has two parts. The larger one — “Old Age and Survivors Insurance” (OASI), established in 1935 — provides retirement benefits to those who have worked for more than 10 years, their spouses, and their dependent children. It also pays benefits to survivors of deceased workers.

The other part of Social Security is “Disability Insurance” (DI), added in 1956. This program provides monthly benefits to workers with disabilities who have not yet retired, as well as their spouses and dependent children. To qualify for DI, one must have paid into Social Security and met minimum work requirements prior to experiencing physical or mental impairment.

In both parts of Social Security, benefits are designed to replace part of what individuals earned during their working years. Those with lower earnings get a higher replacement percentage than higher-earning workers, with replacement rates ranging from anywhere between 90 percent to 28 percent.

An individual’s retirement benefits are determined based on average monthly earnings from his or her 35 highest-earning years. The age at which retirement benefits begin also impacts their amount. If you claim benefits before the full retirement age, your monthly benefits are reduced in order to spread the same amount of benefits over more years. Conversely, waiting until after the full retirement age to claim benefits increases the monthly benefit amount.

The full retirement age, originally set at 65, is currently 66 and rises to age 67 for everyone born in 1960 or later.

Once someone begins receiving benefits, they receive an annual cost-of-living adjustment (COLA) so their monthly benefit keeps pace with inflation.

How is Social Security financed?

Social Security is primarily financed by a 12.4 percent payroll tax on an employee’s wages. Half of the tax is taken out of an employee’s paycheck and half is paid directly by the employer. Self-employed individuals pay both halves of the tax. No Social Security taxes are paid on income beyond a certain amount — the “wage cap” — each year ($127,200 in 2017).

Social Security is also partly funded by income taxes paid on benefits. Such benefits were once exempt from the income tax, but now for middle-income individuals and couples (earning around $35,000 and $45,000 respectively) up to 85 percent of benefits are considered taxable income.

Importantly, Social Security tax revenue from current workers is used to directly pay for the benefits of current retirees.

Between 1984 and 2009, revenues exceeded spending on benefits and the U.S. Treasury “borrowed” the surplus revenue — leaving bonds in the Social Security Trust Fund as IOUs from one arm of the government to another. When spending on benefits exceeds revenue, Social Security redeems these bonds. If the bonds in the Social Security trust fund are eventually exhausted, current law requires that benefit payments be cut to match the level of revenues coming in to Social Security.

What challenges does Social Security face?

Social Security currently pays out tens of billions of dollars more in benefits than it collects in taxes, a gap that is only projected to get worse as time goes on. By the early 2030s, absent reforms, the Social Security Trust Fund will be exhausted and Social Security benefits will be cut by around 25 percent to match revenue levels.

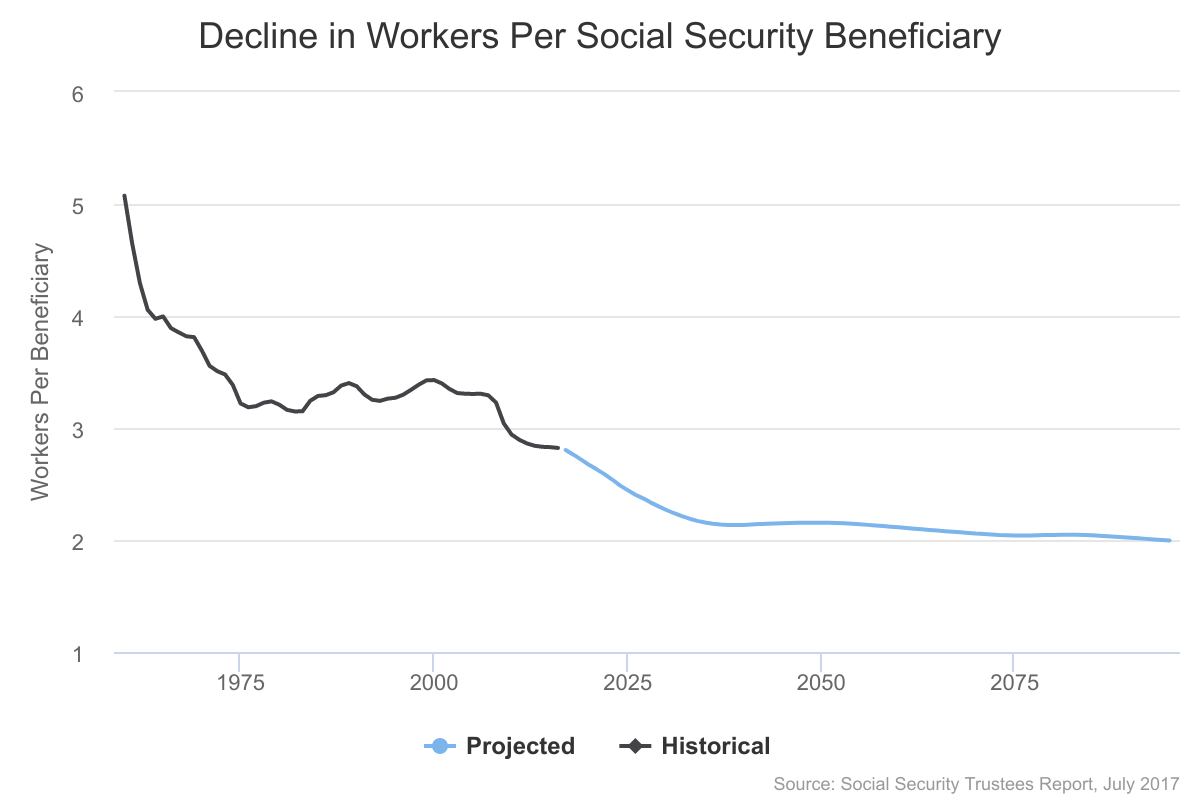

This financial challenge is largely the result of demographic changes. The baby boom generation’s workforce participation and retirement combined with rising life expectancy in retirement and declining fertility rates have resulted in fewer workers paying into the system per individual receiving benefits from it. In 1960, the ratio of taxpaying workers to Social Security beneficiaries was five to one. Today, there are fewer than three workers for every beneficiary. And by 2030, the number of workers paying the benefits of each beneficiary will drop to just around two.

The result is that revenues under current law are insufficient to finance scheduled benefits. Social Security’s financial challenges have been further exacerbated by rising income inequality, as a greater proportion of income is earned above the taxable maximum now than when the wage cap was last adjusted legislatively in 1983.

In the interim, Social Security is able to pay benefits in full by drawing down on its trust fund assets. However, because these assets are intragovernmental debt and not actual savings, the federal government must borrow from the public to finance Social Security’s annual shortfalls just as it does for any other deficit spending.

How can we fix Social Security?

There are only two types of solutions to the financing problems in Social Security. You can either raise revenue to make up for the insufficiency of the current wage tax or you can reduce spending to make up for increasing benefit payments.

Most bipartisan plans proposed by think-tanks, commissions and groups of legislators does a combination of those solutions, just like the most recently passed major legislation to reform Social Security in 1983. Then, the package passed by Congress and the President increased payroll taxes and reduced future benefit payments by raising the full retirement age.

The key for the future of Social Security and future generations expecting Social Security to be sustainable over the long term and remain part of the social safety net, is to act sooner rather than later. As the Trustees of the Social Security program point out in their annual reports, acting sooner allows more time to phase in changes and give the public time to prepare while minimizing negative consequences for low-income individuals, vulnerable populations, and those already dependant on the program.

Continue Reading