I. What’s the Debt?

How big is the U.S. national debt?

Some reports say that it’s $36 trillion and others say it’s $29 trillion.

The two numbers may cause some confusion but both are correct. They simply measure two different things. The larger number is the gross debt, which consists of all forms of U.S. government debt, including non-marketable trust fund debt that the government owes to itself. A good example is the Social Security trust fund.

The smaller number, which is still pretty big, is the debt held by the public. It consists of marketable debt that the government sells to finance its operations. Holders of this debt are domestic and foreign purchasers, including individuals, corporations, state or local governments, the Federal Reserve, foreign governments, and others outside the U. S. government.

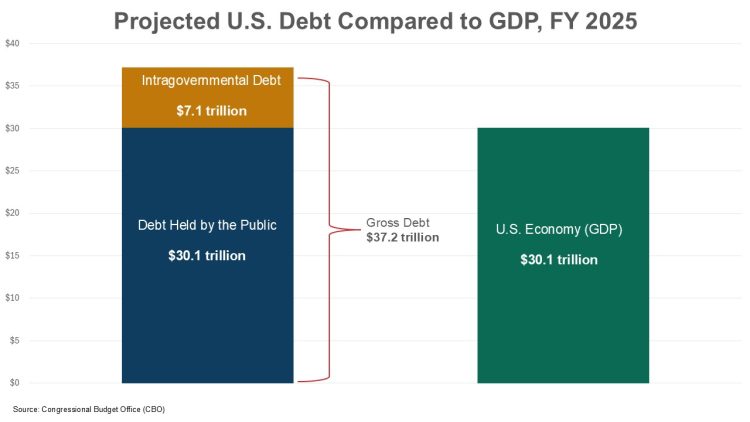

As of May 8, 2025, gross debt was $36.2 trillion and debt held by the public was $28.9 trillion. The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projects that by the end of fiscal year 2025 the gross debt will be $37.2 trillion and debt held by the public will be $30.1 trillion.

Debt numbers are more meaningful when compared to the size of the gross domestic product (GDP). As the Treasury Department explains: “Comparing a country’s debt to its gross domestic product reveals the country’s ability to pay down its debt. This ratio is considered a better indicator of a country’s fiscal situation than just the national debt number because it shows the burden of debt relative to the country’s total economic output and therefore its ability to repay it.”

By this measure, CBO projects that at the end of fiscal year 2025, gross debt will be 123 percent of GDP and debt held by the public will be 100 percent of GDP.

II. What Makes Up the Gap Between Gross Debt and Debt Held by the Public?

The gap between the gross debt and debt held by the public consists of another form of borrowing called intragovernmental debt. The Treasury Department describes this as “debt that one part of the U.S. Federal Government owes to another part. This represents cases where Social Security, Medicare, and other federal programs collect more revenue than they need in a year and then purchase Treasury debt for their trust funds.”

Because intragovernmental debt is essentially money owed from one arm of the government (Treasury) to another (Social Security, for example), economists and many official reports on the nation’s financial status tend to focus on debt held by the public. As CBO explains this is “a measure that indicates the extent to which federal borrowing affects the availability of private funds for other borrowers. All else being equal, an increase in government borrowing reduces the amount of money available to other borrowers, putting upward pressure on interest rates and reducing private investment.”

You will often hear this referred to as a “crowding out” effect, which becomes a problem when investors are drawn to purchase large amounts of government debt rather than investing in the private sector and stimulating productivity, innovation and growth. Also important to note is that our federal debt is heavily weighted toward on-going operating expenses, rather than key investments in human and physical capital which are important for a dynamic future economy.

While the gross debt is a larger number, CBO observes that it “can be challenging to use as an indicator of the government’s overall financial position because about one-fifth of gross federal debt is held in federal trust funds, mostly for Social Security, federal and military retirement programs, and Medicare. When outlays exceed revenues for such a program, gross debt is unchanged even though the government’s overall financial position has worsened.” In other words, in these cases, debt is no longer intergovernmental debt but now has to be financed by selling the debt on the open market (or to the “public”). Gross debt doesn’t change, but publicly held debt does.

While the intergovernmental debt doesn’t compete with private sector investment in the same way that publicly held debt does, it does represent a very real claim on public dollars to pay for programs like Social Security benefits and Medicare. We cannot just “forgive” the debt we owe ourselves without a significant impact on beneficiaries of programs that hold this debt.

In different analyses, debt held by the public is the preferred measure for assessing the impact of the federal debt on private debt markets and interest rates because it is the amount of debt that is competing for public funds. Gross debt is the most comprehensive measure of federal debt obligations.

III. What is the Future Path of Gross Debt and Debt Held by the Public?

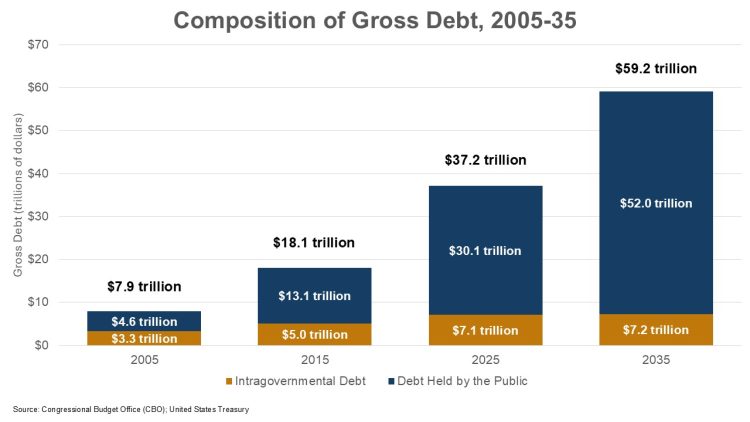

Over the next 10 years, holding current law constant, CBO projects that gross debt will climb to $59.2 trillion (135 percent of GDP) and debt held by the public will climb to $52 trillion (118 percent of GDP). Both would set new record highs. The highest gross debt was recorded in 2020 at 126 percent of GDP and the record for debt held by the public was 106 percent of GDP in 1946.

Looking out over the next 30 years, CBO projects that the gap between gross debt and debt held by the public will substantially close as today’s trust fund balances for Social Security and Medicare are drawn down, thereby converting intragovernmental debt into debt held by the public. This happens because, as CBO explains, “When outlays for a program such as Social Security exceed its revenues, the Treasury issues debt to the public to cover the shortfall and finance payments to beneficiaries. After that issuance of securities to the public, the Treasury redeems a corresponding amount of securities from the trust funds, which reduces the debt held by government accounts.”

Today, intragovernmental debt makes up 19 percent of the gross debt, but by 2035 that share will be down to 12 percent and in 2055, the last year of CBO’s long-term outlook, intragovernmental debt will comprise only 8 percent of the gross debt.

The main factor driving both the gross debt and debt held by the public higher is large, chronic, widening budget deficits that must be financed through the financial markets. So regardless of whether one chooses to use the gross debt or debt held by the public, we are on an unsustainable course.

Continue Reading