Baseball season is underway, but the most consequential pickle play of the season won’t take place at Fenway, Wrigley or any other storied diamond. Rather, the major league action is underway right now (in slow motion) at the Federal Reserve.

In baseball, a player caught in a pickle is stranded between two bases, unable to advance or retreat because two infielders have trapped the runner in the middle. The fielders quickly throw the ball back and forth to each other while narrowing the distance between them, shrinking the base runner’s footpath. Runners succeed only when a fielder drops the ball or misses a throw.

The Fed’s pickle is similar. At first base is a tight labor market and (still) uncomfortably high inflation. These conditions suggest the Fed should remain aggressive in raising interest rates to keep inflation expectations “anchored” and prevent a potential wage-price spiral. At second base, however, is a slowing economy, tightening credit conditions, and multiple mid-size bank failures—all of which suggest the Fed should pause rate hikes or even reduce interest rates to ward off a recession and additional bank failures. Moreover, a new rogue “player” is now on the field—a potential federal debt default. How does the Fed return safely to base (first or second) without tanking the economy or re-igniting inflation?

The Case for Higher Interest Rates: Inflation and a Tight Labor Market

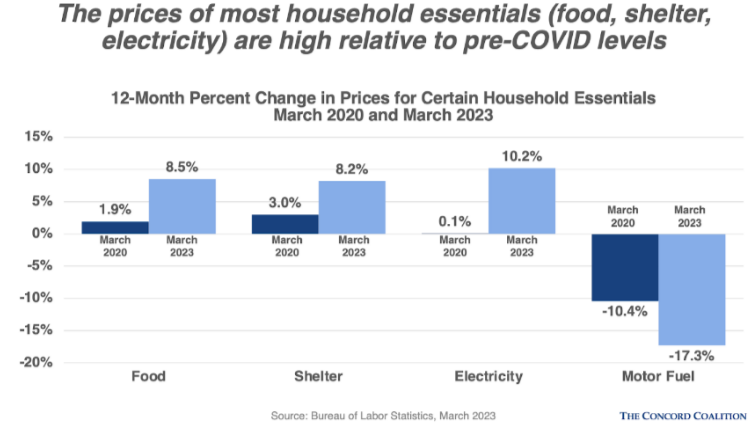

The most recent inflation report (for March 2023) showed that despite a year of aggressive interest rate increases by the Federal Reserve, inflation remains a real threat to household finances. Overall inflation has moderated, falling from nearly 9 percent in June 2022 to 5 percent in March 2023, but the price of many essentials is still very high. Plus, there is no indication that inflation is within spitting distance of the Fed’s 2 percent target.

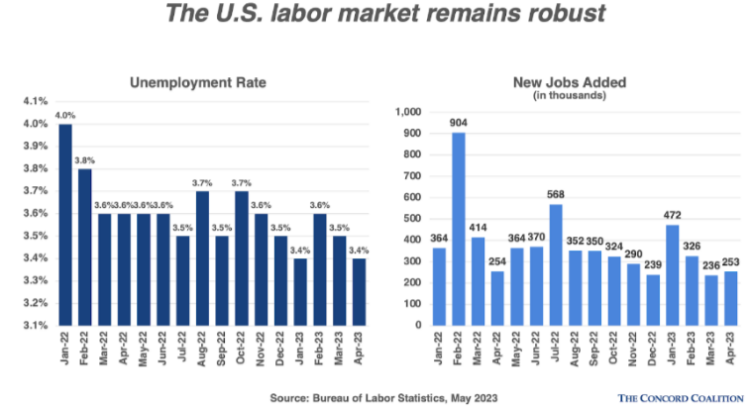

In addition, the U.S. jobs market remains remarkably (unbelievably?) resilient despite the Fed’s rapid pace of rate increases. Over 850,000 additional workers have entered the labor market since the beginning of the year, yet the unemployment rate has steadily fallen from 3.6 percent in February to 3.4 percent in April. According to Friday’s jobs report, employers accelerated their pace of hiring in April, adding a robust 253,000 workers to their payrolls.

When high inflation and a tight labor market collide, concerns emerge about a potential wage-price spiral. This happens when workers’ expectations about future inflation move higher and, as a consequence, leads them to secure even larger wage increases. Producers then pass their higher labor costs onto consumers in the form of higher prices, thereby creating the very inflation that workers were concerned about initially. Workers then respond to the higher actual inflation by adjusting upwards their expectation about future inflation again and the vicious cycle repeats.

History shows that this kind of wage-price spiral is hard to break without significant economic harm. Thus, the Federal Reserve has a vested interest in curbing inflation quickly before expectations about future inflation move above the Fed’s 2-percent target. The Fed has raised the upper bound of its benchmark interest rate from zero to 5.25 percent in 15 months–a heady pace–and while there is a lag associated with monetary policy (it takes awhile for the effect of higher interest rates to filter through the economy) most economists are surprised at the resilience of both inflation and the labor market. Additional rate hikes may be necessary to reduce inflation and cool the jobs market further.

The Case for a Pause or Lower Rates: Slowing Economy, Credit Crisis, Bank Failures

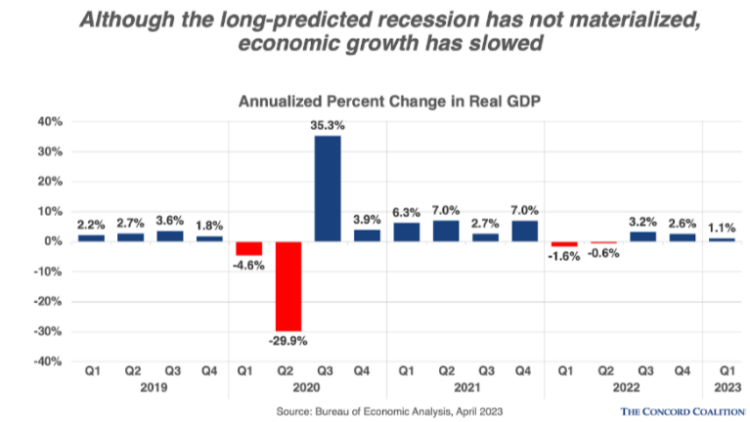

For the last 15 months, inflation has been the singular concern for Fed officials, but recently new threats have emerged: decelerating economic growth and a banking crisis.

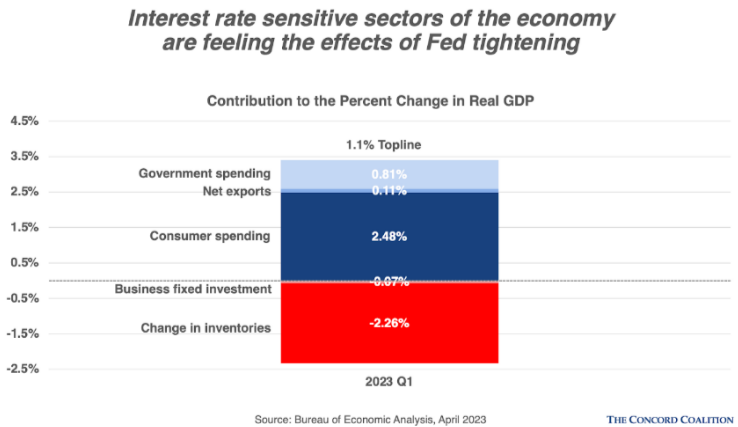

Although rising interest rates have done little to chill the labor market thus far, interest rate sensitive sectors of the economy are beginning to feel the effect. According to the Bureau of Economic Analysis, real GDP grew just 1.1 percent in the first quarter of 2023, a significant slowdown from the robust pace in the last half of 2022.

While consumers continued to spend early in the year, real GDP was hurt by declines in housing and nonresidential investment, and a spend-down in business inventories (why stock up if you think a recession is around the corner?). Economists worry that further rate increases will tip the U.S. economy into recession.

In addition to weak investment, the high profile failure of several mid-size regional banks (Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank, First Republic Bank, and now perhaps PacWest) also places pressure on the Fed to reduce interest rates—or at least hit “pause” on future increases. The Fed’s rapid rise in interest rates caught many banks flat-footed as their depositors withdrew cash in above-normal amounts to invest in newly-issued, higher-yielding bonds. To meet their liquidity requirements, many banks had to sell their own older, lower-yielding investments at a loss, adding to their financial woes. Add to the mix a 2018 regulatory environment that exempted many of the mid-size banks from stress tests and it’s easy to see how the Fed’s efforts to combat inflation inadvertently led to a good old-fashioned bank run–and it’s not clear if more are yet to follow.

A New Rogue Player: A Debt Default

Since January, the Treasury has been deploying “extraordinary measures” to avoid breaching the statutory debt limit. On May 1, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen alerted Congress and President Biden that the federal government could default on its debt obligations as early as June 1, months earlier than initially projected. Income tax collections have been lower than expected, especially following the April deadline for tax year 2022 payments. In a nutshell, the federal government is staring down its own (self-imposed) liquidity crisis.

Despite warnings from all corners, President Biden and Congressional Republicans are nowhere near a potential compromise (in keeping with the baseball metaphor, they aren’t even in the same ballpark). President Biden and Congressional Democrats are insisting on a “clean” debt limit increase while Republicans are demanding fantasy-level spending cuts as a precondition for raising the debt limit. Adding to the sense of urgency: there are only 8 legislative days remaining in May where both the House and Senate are in session. President Biden has called Congressional leaders of both parties to the White House, but that meeting won’t take place until May 9.

Previous run-ups to the “X-date” reveal that adverse consequences often emerge days and weeks in advance as financial markets seek safety in the face of growing uncertainty. This suggests that lawmakers have even less time to adopt a solution to avoid the destabilizing effects of interest rate spikes, gyrating asset prices, and currency fluctuations.

The Federal Reserve has no direct role in resolving the debt limit impasse (other than to gently prod lawmakers to the negotiating table), but it might have to play an outsize role in steering the economy during a period of default. There is no historical precedent for an intentional U.S. debt default so the Fed’s playbook is untested. There is no doubt, however, that the debt limit impasse is a rogue player on the field that unnecessarily complicates the Fed’s pickle play between higher and lower interest rates.

What does this have to do with Fiscal Policy?

Followers of The Concord Coalition know that we rarely comment on Federal Reserve policy–it’s not our area of expertise. But the federal government has amassed so much debt that rising interest rates now have a very real, deleterious effect on the federal budget.

In February, the nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) projected net interest costs would total $640 billion in FY 2023, a 35 percent increase over the prior year. It is expected to revise that number upwards when it issues new projections on May 12. Additional context: CBO anticipates that net interest costs in FY 2023 will consume 10 percent of total federal outlays—more than the federal government’s contribution to Medicaid. Even under the current baseline, interest costs reach a record high 3.3 percent of GDP by 2030. The federal government simply can’t afford higher interest rates.

What is the Fed Signaling?

After two days of discussion on May 2-3, Fed officials unanimously agreed to raise the upper bound of the benchmark Federal Funds rate by 25 basis points, from 5.00 to 5.25 percent. While this outcome was broadly anticipated, financial markets parsing the Fed’s press release or Chairman Powell’s press conference for implicit signals of the future came away disappointed. In rationalizing its outlook, the Fed wrote:

In determining the extent to which additional policy firming may be appropriate to return inflation to 2 percent over time, the Committee will take into account the cumulative tightening of monetary policy, the lags with which monetary policy affects economic activity and inflation, and economic and financial developments.

Statement by the Federal Open Market Committee of the Federal Reserve, May 3, 2023

In layman’s speak: anything is possible. The pickle play continues….