Members of Congress have many responsibilities but their most essential task each year is to complete the 12 discretionary appropriations bills that fund the federal government for the upcoming fiscal year. Budget law requires lawmakers to finish this work before October 1, the start of the federal fiscal year. Since the inception of this requirement in the 1970s, however, Congress has achieved this task only four times (in 1977, 1989, 1995, and 1997). Often, it takes the pending arrival of Santa Claus and the turn of the calendar year to spur Congress into appropriations action.

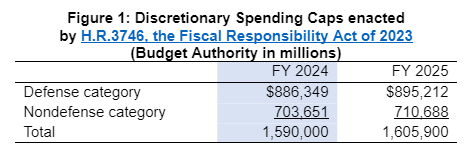

If budget-watchers thought this year would be different, however, they had good reason to be optimistic. When President Biden and House Speaker Kevin McCarthy (R-CA) resolved the debt limit standoff just after Memorial Day, the legislation codifying their deal (H.R.3746, the Fiscal Responsibility Act of 2023) included spending caps for total “base” discretionary appropriations for 2024 and 2025 (see Figure 1). With this common starting point established, House and Senate appropriations committees could immediately start drafting, debating, and passing the 12 appropriations bills for FY 2024. Perhaps the 2024 appropriations cycle would be completed on time!

Wheels Fall off the Appropriations Bus

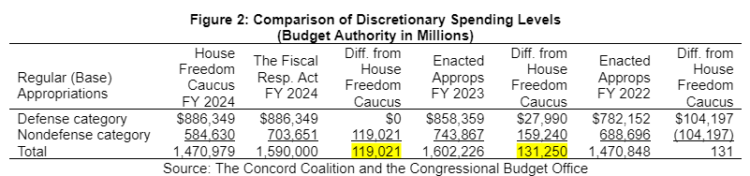

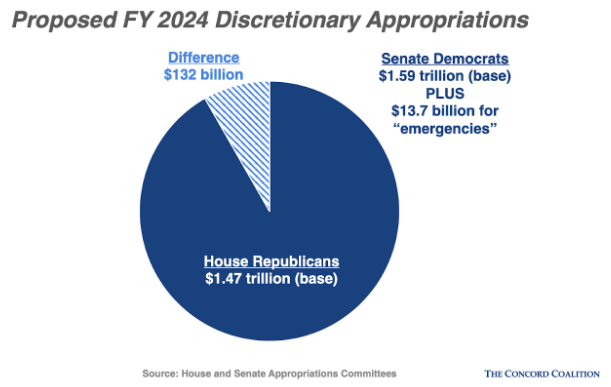

The House and Senate both ran into trouble however, when certain factions in each chamber chose to “reinterpret” the 2024 spending caps. In the House, members of the House Freedom Caucus wanted to reduce FY 2024 discretionary spending to FY 2022 levels and they vowed to oppose appropriations bills marked up to the new caps—and the procedural votes needed to get them on the floor—unless additional cuts were made. They interpreted the caps in the debt limit deal as a ceiling, not a floor (and to be honest they’re not wrong, but their viewpoint does not reflect the spirit of the agreement). Moreover, to achieve that goal, House lawmakers would have to approve spending bills that cut $119 billion from the 2024 cap—all of which the House Freedom Caucus wanted to take from the nondefense side of the budget (a nonstarter for Democrats). It would also result in a 2024 spending level that was $131 billion lower than enacted in 2023 (see Figure 2).

Unfortunately for Speaker McCarthy, this approach divided his caucus. Moderate House Republicans in key swing districts (through which the House Republican majority is derived) are opposed to spending cuts that will be unpopular with their constituents, especially when they know the cuts would not survive the Senate. In their minds, why take an unnecessary political hit? Clearly, getting appropriations bills out of the House this year will be challenging.

In the Senate, Republican defense hawks teamed up with Democrats to add $13.7 billion in “emergency” spending above the agreed-upon caps. According to budget law, emergency- designated spending is exempt from the caps—it does not trigger the sequester that would normally happen when spending exceeds the statutory limits. Technically this designation is allowed, but just like the House Freedom Caucus, the Senate’s position violates the spirit of the original debt limit agreement. The Senate will have its own challenges getting spending bills across the floor since chamber rules require 60 votes to end debate on any measure. Democrats have a two-seat majority in the Senate which means they will need the support of at least 8 Republicans to move their spending bills (more if some Progressive Democrats defect).

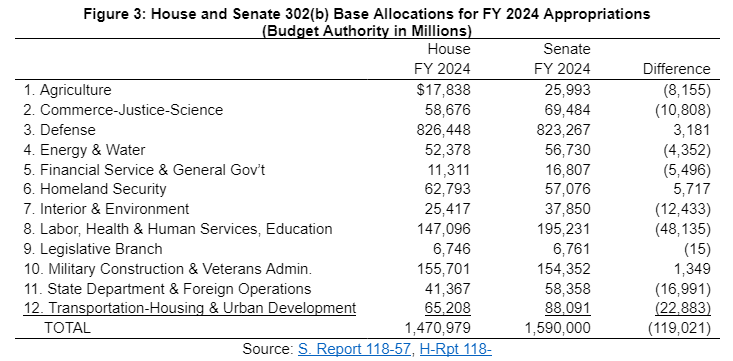

Not only are the two chambers moving in different directions from the topline spending caps for 2024, but they’re also taking very different approaches to the 12 appropriations bills that emanate from those caps (see Figure 3). Not surprisingly, the House Freedom Caucus wants to spend more on defense, border security, and veterans, while Senate Democrats want to spend more on social services, climate change, and infrastructure.

Does This Mean a Government Shut-Down is Inevitable?

Congress almost certainly will miss the October 1 deadline to complete the appropriations process. At the time of this publication, the House and Senate Appropriations Committees were working diligently in committee to approve their bills, but neither chamber had brought a single spending bill to the floor for a vote. Without enacted appropriations for FY 2024, lawmakers will face two choices in September: shutter the government at the end of the month or enact a temporary stop-gap spending measure called a continuing resolution (CR). A CR allows a federal agency to operate at the same rate and level of spending as it did under the most recent full-year appropriations measure (in this case, H.R.2617, the Consolidated Appropriations Act for Fiscal Year 2023).

A CR seems like a nifty tool, but it isn’t painless. The constraints imposed by a CR are problematic in any year, regardless of the political environment—restrictive funding that reduces or delays a variety of actions (e.g., hiring, awarding contracts and grants), uncertainty that hampers future planning, prohibitions on new “starts,” and the increased administrative burden of simply complying with the restrictions. In short, agencies really dislike CRs.

In a normal year, a divided Congress at an appropriations crossroads would work to pass a “clean” CR—a CR with little or no extraneous matter—but a unique confluence of events in 2023 makes a clean CR in September almost impossible. First, inflation continues to erode federal purchasing power (just like households) putting pressure on lawmakers to add “anomalies” to the CR that allow agencies to spend more and/or spend faster. Second, both the Pentagon and the State Department will need additional funds to support Ukraine in its battle for sovereignty (the White House has not submitted a supplemental request yet, but a spokesman has said it will). Third, the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) will need at least $10 billion to replenish the Disaster Relief Fund or it could run out of money during the August recess (with hurricane season already underway). And last but not least, the official end of the coronavirus emergency and Title 42 in May means additional money is needed for border security, humanitarian aid, and immigration processing to address the crisis at the southern border.

A CR also carries over the policies contained in the previous full-year appropriations bills. When the FY 2023 consolidated appropriations bill was enacted, Democrats controlled the House, the Senate, and the White House—and the 2023 spending bills reflected their ideologies on a host of contentious issues: family planning, immigration and border security, funding for the IRS, and more. It’s hard to see a conservative House Republican majority supporting a CR without some policy modifications, adding another complication to enactment.

The final kicker: both chambers have very narrow majorities. That means a very small group of determined lawmakers in either the House or the Senate could easily derail a CR and cause a shutdown.

At this juncture, it certainly seems that the roadmap to a CR in September is murky, at best. Ultimately however, a September CR will probably mirror the path of the Democrat’s reconciliation bill in 2022. At that time, President Biden’s Build Back Better legislation was deemed dead, but at the last possible moment (literally) it was miraculously resurrected by an agreement with Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV). In other words, the path to a CR will seem impossible until suddenly it’s possible.